A Disappointing Debut

The New York Times - January 31, 2008 - EDITORIAL

About the best we can say about Attorney General Michael Mukasey’s testimony Wednesday in the Senate is that he was no Alberto Gonzales, with the frequent memory lapses and possibly intentional misstatements. But that is a very low bar. On torture, domestic spying and other important matters, Mr. Mukasey parroted the Bush administration’s deplorable line. He was particularly disappointing in his see-no-evil approach to the misconduct at the Justice Department before he arrived.

The American people deserve better from their highest law-enforcement official, who was making his first appearance before the Senate Judiciary Committee since taking office in November. To a disturbing degree, he has adopted his predecessor’s habit of saying precisely what the White House wanted to hear.

It should not have been hard for Mr. Mukasey to admit that waterboarding — the odious practice of making prisoners believe they are about to be drowned — is torture. He frankly conceded that if it were done to him it “would feel that way.” But he weaved and dodged questions from senators about whether it is torture when it is done to other people, and whether it is illegal.

Mr. Mukasey also pushed Congress to give immunity to telecommunications companies for any illegal acts they committed while helping the administration carry out its outlaw domestic spying program. Mr. Mukasey is responsible for enforcing the law. Pushing Congress to immunize lawbreakers, especially before it learns what laws were broken, is inconsistent with this duty.

Mr. Mukasey took office in the wake of a scandal — accusations that federal prosecutions were politicized, that nonpolitical positions were filled with partisans and that Mr. Gonzales lied about it to Congress. These serious charges did not go away simply because Mr. Gonzales did. Mr. Mukasey needs to ensure that they are investigated, and to assure the public that any misconduct in his department has been cleaned up.

He has yet to do so. In his written testimony, Mr. Mukasey ignored the scandal that roiled his department last year. His answers to questions from senators on the subject were lackadaisical. He seemed to know and care little about well-publicized charges by Scott Bloch, the chief of the Office of Special Counsel, that the Justice Department is impeding his investigation.

Mr. Mukasey was equally disappointing about the refusal of certain administration witnesses to answer Congressional subpoenas to testify about the United States attorneys scandal. He suggested that if the administration believes that executive privilege shields them, that ends the matter. He could not be more mistaken.

Mr. Mukasey has taken some important steps to depoliticize the Justice Department, notably establishing a better wall between the White House and the department. His testimony was an unfortunate reminder, however, that he has yet to show the independence and respect for the rule of law that the job requires.

The New York Times Company

MLK said: "Injustice Anywhere is a Threat to Justice Everywhere"

End Corruption in the Courts!

Court employee, judge or citizen - Report Corruption in any Court Today !! As of June 15, 2016, we've received over 142,500 tips...KEEP THEM COMING !! Email: CorruptCourts@gmail.com

Most Read Stories

- Tembeckjian's Corrupt Judicial 'Ethics' Commission Out of Control

- As NY Judges' Pay Fiasco Grows, Judicial 'Ethics' Chief Enjoys Public-Paid Perks

- New York Judges Disgraced Again

- Wall Street Journal: When our Trusted Officials Lie

- Massive Attorney Conflict in Madoff Scam

- FBI Probes Threats on Federal Witnesses in New York Ethics Scandal

- Federal Judge: "But you destroyed the faith of the people in their government."

- Attorney Gives New Meaning to Oral Argument

- Wannabe Judge Attorney Writes About Ethical Dilemmas SHE Failed to Report

- 3 Judges Covered Crony's 9/11 Donation Fraud

- Former NY State Chief Court Clerk Sues Judges in Federal Court

- Concealing the Truth at the Attorney Ethics Committee

- NY Ethics Scandal Tied to International Espionage Scheme

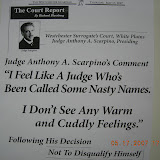

- Westchester Surrogate's Court's Dastardly Deeds

Thursday, January 31, 2008

NY Times Editorial on AG Mukasey (MORE, CLICK HERE)

Fake Lawyer Earned Real 225k as Staff Attorney (MORE, CLICK HERE)

BOGUS ATT'Y TAKES A TRIP

The New York Post By LAURA ITALIANO - January 31, 2008 -- Brian Valery loved being a lawyer.

He worked as much as 70 hours a week at one of the city's top insurance-litigation firms for two years, helping some 50 clients win cases. Valery even earned an annual salary of $155,000. But there was one problem: Valery wasn't a lawyer. He hadn't even attended law school.

Valery, 33, of Massapequa Park, LI, stood yesterday before a Manhattan judge, who sentenced him to five years of probation for pulling off the elaborate masquerade. "I guess he got away with it so long because he was so talented, and so hardworking," said Valery's lawyer, Bob LaRusso. "He worked 60, 70 hours a week. He worked longer hours than I ever did."

The punishment came after it was discovered that Valery had fibbed his way up the ladder at insurance-litigation heavyweight Anderson Kill & Olick - going from a lowly, $21,000-a-year paralegal to earning $155,000 as a staff attorney.

By the time he got caught - after a friend saw his name in connection with a big liability case involving the painkiller OxyContin, and did some digging - he'd helped some 50 clients at the 130-lawyer firm.

Valery's ruse was as time-consuming as it was intricate. He'd begun by telling his trusting bosses he was attending Fordham Law School. Truth was, he didn't even possess an undergraduate degree. Bizarrely, Valery twice told his bosses he'd flunked the bar, only to give them the good news of his "passing" in 2003 - all of it untrue.

Yesterday, Valery was calm during his brief sentencing - but flipped out when he saw photographers waiting outside.

He nearly got run over by a car as he dashed across Lafayette Street, then slipped and fell to his knees while attempting to bob and weave evasively on the rain-slicked sidewalk. "Leave me alone! Leave me alone!" he shouted.

In addition to probation, Valery has to pay back $225,000 in ill-gotten salary to the firm, and serve 100 hours of community service.

laura.italiano@nypost.com

The New York Post By LAURA ITALIANO - January 31, 2008 -- Brian Valery loved being a lawyer.

He worked as much as 70 hours a week at one of the city's top insurance-litigation firms for two years, helping some 50 clients win cases. Valery even earned an annual salary of $155,000. But there was one problem: Valery wasn't a lawyer. He hadn't even attended law school.

Valery, 33, of Massapequa Park, LI, stood yesterday before a Manhattan judge, who sentenced him to five years of probation for pulling off the elaborate masquerade. "I guess he got away with it so long because he was so talented, and so hardworking," said Valery's lawyer, Bob LaRusso. "He worked 60, 70 hours a week. He worked longer hours than I ever did."

The punishment came after it was discovered that Valery had fibbed his way up the ladder at insurance-litigation heavyweight Anderson Kill & Olick - going from a lowly, $21,000-a-year paralegal to earning $155,000 as a staff attorney.

By the time he got caught - after a friend saw his name in connection with a big liability case involving the painkiller OxyContin, and did some digging - he'd helped some 50 clients at the 130-lawyer firm.

Valery's ruse was as time-consuming as it was intricate. He'd begun by telling his trusting bosses he was attending Fordham Law School. Truth was, he didn't even possess an undergraduate degree. Bizarrely, Valery twice told his bosses he'd flunked the bar, only to give them the good news of his "passing" in 2003 - all of it untrue.

Yesterday, Valery was calm during his brief sentencing - but flipped out when he saw photographers waiting outside.

He nearly got run over by a car as he dashed across Lafayette Street, then slipped and fell to his knees while attempting to bob and weave evasively on the rain-slicked sidewalk. "Leave me alone! Leave me alone!" he shouted.

In addition to probation, Valery has to pay back $225,000 in ill-gotten salary to the firm, and serve 100 hours of community service.

laura.italiano@nypost.com

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

Fraud Counts against Westchester Law Firm Continue, says Federal Judge (MORE, CLICK HERE)

NY Firm Faces Allegations of Double-Crossing Embattled Client

by Beth Bar - New York Lawyer - January 30, 2008

Stressing that the case raised "important issues concerning the integrity of the bankruptcy process," a federal bankruptcy judge in Manhattan has declined to dismiss claims by a trustee against a Westchester-based law firm.

In In re Food Management Group (Grubin v. Rattet), 04-22880, Judge Martin Glenn ruled that allegations of fraudulent concealment, breach of fiduciary duty, negligence and fraud on the court could proceed against attorneys Robert L. Rattet and Jonathan S. Pasternak, as well as the law firm Rattet, Pasternak & Gordon Oliver.

The lawyers and the firm are accused of failing to disclose that an "insider" of debtor Food Management Group had violated a court order by submitting a bid in the auction of the company's assets.

The trustee also alleged that the lawyers improperly failed to disclose that they had represented one of the insiders before the auction.

Judge Glenn said that if the allegations are proven, the attorneys and their firm engaged in "serious wrongdoing."

"We deny liability," John Collen of Quarles & Brady in Chicago, who represents the lawyers, said in an interview yesterday. "The decision merely requires us to answer a complaint. It does not contain any findings of liability or wrongdoing."

He declined to elaborate further.

The lawyers were hired to represent Food Management, which managed 24 Dunkin' Donuts franchises when it filed for bankruptcy on June 1, 2004.

Janice E. Grubin, Food Management's chapter 11 trustee, filed her complaint against the firm and a host of other parties in February 2007. She is seeking to recover damages arising from what she said was an unlawful scheme by the lawyers, their firm and others who "colluded to effect a fraudulent sale of [bankruptcy] estate assets to and for the benefit of [Food Management's] principals, Anastasios Gianopoulos and Constantine Gianopoulos . . . without disclosing such to the Court."

The Gianopouloses had been sued by Dunkin' Donuts in 2000 for failure to pay franchise fees. As part of an Oct. 18, 2002, settlement of that case, the Gianopouloses agreed not to have any further involvement, directly or indirectly, with Dunkin' Donuts franchises. But Ms. Grubin said Messrs. Rattet and Pasternak and their firm helped the Gianopouloses get around this agreement.

The lawyers filed a motion on Jan. 11, 2005, on behalf of Food Management seeking authorization to conduct an auction of the debtors' property. Judge Glenn granted the motion on Feb. 22, 2005.

"The Bidding Procedures provided that any offer be 'a good faith, bona fide, offer to purchase' and required that each bidder 'fully disclose the identity of each entity that will be bidding for a[n] Asset or otherwise participating in such a bid, and the complete terms of any such participation,' and that each bidder submit a registration form certifying that the bidder was not an insider of the Debtors," Judge Glenn explained in his decision.

But Ms. Grubin alleged that between March 1 and March 16, 2005, the attorneys and firm had discussions with the Gianopouloses concerning the sale of Food Management's assets. She said that Thomas Borek, a principal of a company called 64 East who had been a Rattet Pasternak client, was present at the March 16 meeting.

Meanwhile, 64 East was one of the two companies that bid. Dunkin Donuts ultimately rejected 64 East's bid, and the trustee said that without her consent Mr. Rattet attempted to have Mr. Borek's $2.1 million returned to him. She also charges that the law firm concealed the fact that 64 East was a front for the Gianopouloses and that they had funded the deposit.

"The Debtors have suffered damages as a direct result of the fraudulent concealment in that the $2.1 million would not have been returned to 64 East had . . . Rattet and the Rattet Law Firm complied with their duties as officers of the Court and disclosed the agreement with 64 East concerning the purchase of Debtors' property," Ms. Grubin alleged in her complaint. "Rather, those funds would have been retained by the Trustee and made available to satisfy the allowed claims of creditors."

According to the decision, in September 2005, Ms. Grubin ordered the lawyers to have "no further involvement in the case."

She is asking Judge Glenn to hold the Gianopouloses, the law firm and the attorneys jointly and severally liable for at least $2.1 million. The trustee is also seeking punitive damages and the disgorgement of all compensation paid to the attorneys.

Judge Glenn took no position on the merits but ruled the trustee had standing to bring the action and had presented sufficient facts to survive the motion to dismiss.

In addition to Mr. Collen, Messrs. Rattet and Pasternak and their firm are represented by Gil M. Coogler of White Fleischner & Fino in Manhattan.

Ms. Grubin and the debtors are represented by Warren von Credo Baker of Drinker Biddle & Reath in Chicago. Mr. Baker declined to comment.

by Beth Bar - New York Lawyer - January 30, 2008

Stressing that the case raised "important issues concerning the integrity of the bankruptcy process," a federal bankruptcy judge in Manhattan has declined to dismiss claims by a trustee against a Westchester-based law firm.

In In re Food Management Group (Grubin v. Rattet), 04-22880, Judge Martin Glenn ruled that allegations of fraudulent concealment, breach of fiduciary duty, negligence and fraud on the court could proceed against attorneys Robert L. Rattet and Jonathan S. Pasternak, as well as the law firm Rattet, Pasternak & Gordon Oliver.

The lawyers and the firm are accused of failing to disclose that an "insider" of debtor Food Management Group had violated a court order by submitting a bid in the auction of the company's assets.

The trustee also alleged that the lawyers improperly failed to disclose that they had represented one of the insiders before the auction.

Judge Glenn said that if the allegations are proven, the attorneys and their firm engaged in "serious wrongdoing."

"We deny liability," John Collen of Quarles & Brady in Chicago, who represents the lawyers, said in an interview yesterday. "The decision merely requires us to answer a complaint. It does not contain any findings of liability or wrongdoing."

He declined to elaborate further.

The lawyers were hired to represent Food Management, which managed 24 Dunkin' Donuts franchises when it filed for bankruptcy on June 1, 2004.

Janice E. Grubin, Food Management's chapter 11 trustee, filed her complaint against the firm and a host of other parties in February 2007. She is seeking to recover damages arising from what she said was an unlawful scheme by the lawyers, their firm and others who "colluded to effect a fraudulent sale of [bankruptcy] estate assets to and for the benefit of [Food Management's] principals, Anastasios Gianopoulos and Constantine Gianopoulos . . . without disclosing such to the Court."

The Gianopouloses had been sued by Dunkin' Donuts in 2000 for failure to pay franchise fees. As part of an Oct. 18, 2002, settlement of that case, the Gianopouloses agreed not to have any further involvement, directly or indirectly, with Dunkin' Donuts franchises. But Ms. Grubin said Messrs. Rattet and Pasternak and their firm helped the Gianopouloses get around this agreement.

The lawyers filed a motion on Jan. 11, 2005, on behalf of Food Management seeking authorization to conduct an auction of the debtors' property. Judge Glenn granted the motion on Feb. 22, 2005.

"The Bidding Procedures provided that any offer be 'a good faith, bona fide, offer to purchase' and required that each bidder 'fully disclose the identity of each entity that will be bidding for a[n] Asset or otherwise participating in such a bid, and the complete terms of any such participation,' and that each bidder submit a registration form certifying that the bidder was not an insider of the Debtors," Judge Glenn explained in his decision.

But Ms. Grubin alleged that between March 1 and March 16, 2005, the attorneys and firm had discussions with the Gianopouloses concerning the sale of Food Management's assets. She said that Thomas Borek, a principal of a company called 64 East who had been a Rattet Pasternak client, was present at the March 16 meeting.

Meanwhile, 64 East was one of the two companies that bid. Dunkin Donuts ultimately rejected 64 East's bid, and the trustee said that without her consent Mr. Rattet attempted to have Mr. Borek's $2.1 million returned to him. She also charges that the law firm concealed the fact that 64 East was a front for the Gianopouloses and that they had funded the deposit.

"The Debtors have suffered damages as a direct result of the fraudulent concealment in that the $2.1 million would not have been returned to 64 East had . . . Rattet and the Rattet Law Firm complied with their duties as officers of the Court and disclosed the agreement with 64 East concerning the purchase of Debtors' property," Ms. Grubin alleged in her complaint. "Rather, those funds would have been retained by the Trustee and made available to satisfy the allowed claims of creditors."

According to the decision, in September 2005, Ms. Grubin ordered the lawyers to have "no further involvement in the case."

She is asking Judge Glenn to hold the Gianopouloses, the law firm and the attorneys jointly and severally liable for at least $2.1 million. The trustee is also seeking punitive damages and the disgorgement of all compensation paid to the attorneys.

Judge Glenn took no position on the merits but ruled the trustee had standing to bring the action and had presented sufficient facts to survive the motion to dismiss.

In addition to Mr. Collen, Messrs. Rattet and Pasternak and their firm are represented by Gil M. Coogler of White Fleischner & Fino in Manhattan.

Ms. Grubin and the debtors are represented by Warren von Credo Baker of Drinker Biddle & Reath in Chicago. Mr. Baker declined to comment.

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

Judge Confiscates Transcripts: Funny Business as Usual (MORE, CLICK HERE)

Unsealed, Uncontested Court Records “Confiscated” by Judge Herman Cahn and withheld by Judge Bernard Fried With the Apparent Collusion of Administrative Judge Jacqueline Silbermann. So Says William Galison. And Mr. Galison has a lot more to say on what appears to be just another miscarriage of justice:

This matter regards the wanton violation of 14th amendment rights and section 216.01 of the Unified Rules for NYS trial courts by Judges Herman Cahn and Bernard Fried, with the apparent collusion of Judge Jacqueline Silbermann, all of the New York Civil Supreme Court, First Department. Specifically, this matter involves the illegal confiscation of public record transcripts from the public record and from one litigant with no due process of law.

The underlying case is a libel lawsuit by William Galison, a professional musician, brought against Jeffrey Greenberg, a lawyer from the firm of Beldock, Levine and Hoffman.

In the course of pre-trial hearings, Judge Cahn held an ex parte conference with Greenberg’s lawyers, and on the basis of that meeting, issued a protective order against Galison. Cahn gave no explanation to Galison as to the reason for the protective order, and despite Galison’s numerous requests has refused to furnish the transcripts of the ex parte meeting to Galison for over two years.

THE CONFISCATION OF UNSEALED PUBLIC RECORD COURT DOCUMENTS FROM ONE PARTY IN A COURT PROCEEDING IS A VIOLATION OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATE LAW BY JUDGES IN THE NEW YORK SUPREME COURT UNPRECEDENTED IN THE HISTORY OF THE COURT.

The motivation of Greenberg’s lawyers in defaming Galison is as transparent as it is reprehensible. Galison sued Greenberg because Greenberg wrote and published the false allegation that Galison had “physically abused” Greenberg’s client. Greenberg made this allegation despite his client’s sworn testimony that Galison never harmed her in any way, and that she had never told Greenberg or anyone else that he had done so. In the ex parte meeting, Greenberg’s lawyers falsely told Judge Cahn that Galison posed a threat to THEM in order to prejudice Cahn against Galison and his libel claim.

Of course, the right to obtain court transcripts in one’s own case is a fundamental pillar of the justice system, especially when those transcripts contain ex parte allegations and evidence that have lead to sanctions. In essence, Mr. Galison was accused, tried, sentenced and punished without knowledge of the charges, the evidence or the argument against him, and with no opportunity whatsoever to defend himself..

THERE ARE NO CONTESTED FACTS IN THIS MATTER

Judge Cahn does not contest the fact that he had an ex parte meeting, that he placed a restraining order on Galison, or that he confiscated the transcripts without due process. In fact, there are NO contested FACTS at issue in this matter. The ONLY question at issue is whether or not New York Supreme Court judges are beholden to the rules of the Uniform Court System and the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States. Galison contends that they are. Cahn, Fried and Silbermann contend that they are not.

It must be emphasized that the transcripts in question were NEVER SEALED by Judge Cahn against Galison or anyone else. NOT ONE of the rules regarding sealing of court documents was obeyed. Furthermore, the defense lawyers DO NOT CONTEST the release of the transcripts to Galison. In a letter to judge Silbermann they wrote: “If a transcript of the December 7, 2005 conference with Justice Cahn exists, [we] of course have no objection its being released to the parties”.

The fact that the transcripts exist was made clear by a short portion of the transcripts that Mr. Galison was able to obtain from the court reporter, Myron Calderon. Mr. Calderon told Galison that the entire ex parte meeting was recorded, and that Judge Cahn had “confiscated” most of the record from Calderon before he had a chance to transcribe it.

When Mr. Galison complained to Administrative Judge Silbermann about the confiscation of the transcripts, Judge Cahn immediately recused himself from the case without explanation, against Mr. Galison’s expressed wishes. Even after his recusal however, he has continued to prohibit Mr. Galison from obtaining the transcripts for over two years. When Galison appealed to Judge Silbermann, Silbermann refused to direct Judge Cahn to furnish the transcripts and advised Mr. Galison that his only recourse was to file a formal motion before the judge who replaced Cahn: Bernard Fried, whom Silbermann also personally chose to take over the case. Never in the history of the New York Supreme Court, has a litigant been required to file a motion to obtain an unsealed transcript from the court.

Galison made two formal motions before Fried to obtain the unsealed, uncontested transcripts from his own case. Fried denied the first motion without prejudice, and the second WITH prejudice because, as Judge Fried put it: “I did not give you permission to re-file”. (If a ruling without prejudice cannot be re-filed, how is it difference than a ruling WITH prejudice?)

And so, Mr. Galison has now exhausted all of the available recourses for obtaining the UNSEALED, UNCONTESTED transcripts from his own case. To this day, he does not know why a protective order was placed against him, what evidence was presented and what arguments were made.

Judge Fried then dismissed the entire case in favor of Defense, thereby leaving Galison with no further recourse for obtaining the transcripts. Galison, however is appealing the decision, and hopes that Appellate Court will uphold his fundamental constitutional right to a fair trial.

The ex-parte meeting and the unfair judgment are, unfortunately, commonplace events in the Civil Supreme. What is shocking in this case is the cover up, involving three veteran judges, and their coordinated efforts over two years to deprive a citizen of his basic constitutional rights to obtain the transcripts in his own case.

Mr. Galison has now filed complaints against Judges Cahn, Fried and Silbermann with the Commission on Judicial Conduct.

For more information please contact: William Galison at wgalison@aol.com

Click here to see our previous post on this story.

This matter regards the wanton violation of 14th amendment rights and section 216.01 of the Unified Rules for NYS trial courts by Judges Herman Cahn and Bernard Fried, with the apparent collusion of Judge Jacqueline Silbermann, all of the New York Civil Supreme Court, First Department. Specifically, this matter involves the illegal confiscation of public record transcripts from the public record and from one litigant with no due process of law.

The underlying case is a libel lawsuit by William Galison, a professional musician, brought against Jeffrey Greenberg, a lawyer from the firm of Beldock, Levine and Hoffman.

In the course of pre-trial hearings, Judge Cahn held an ex parte conference with Greenberg’s lawyers, and on the basis of that meeting, issued a protective order against Galison. Cahn gave no explanation to Galison as to the reason for the protective order, and despite Galison’s numerous requests has refused to furnish the transcripts of the ex parte meeting to Galison for over two years.

THE CONFISCATION OF UNSEALED PUBLIC RECORD COURT DOCUMENTS FROM ONE PARTY IN A COURT PROCEEDING IS A VIOLATION OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATE LAW BY JUDGES IN THE NEW YORK SUPREME COURT UNPRECEDENTED IN THE HISTORY OF THE COURT.

The motivation of Greenberg’s lawyers in defaming Galison is as transparent as it is reprehensible. Galison sued Greenberg because Greenberg wrote and published the false allegation that Galison had “physically abused” Greenberg’s client. Greenberg made this allegation despite his client’s sworn testimony that Galison never harmed her in any way, and that she had never told Greenberg or anyone else that he had done so. In the ex parte meeting, Greenberg’s lawyers falsely told Judge Cahn that Galison posed a threat to THEM in order to prejudice Cahn against Galison and his libel claim.

Of course, the right to obtain court transcripts in one’s own case is a fundamental pillar of the justice system, especially when those transcripts contain ex parte allegations and evidence that have lead to sanctions. In essence, Mr. Galison was accused, tried, sentenced and punished without knowledge of the charges, the evidence or the argument against him, and with no opportunity whatsoever to defend himself..

THERE ARE NO CONTESTED FACTS IN THIS MATTER

Judge Cahn does not contest the fact that he had an ex parte meeting, that he placed a restraining order on Galison, or that he confiscated the transcripts without due process. In fact, there are NO contested FACTS at issue in this matter. The ONLY question at issue is whether or not New York Supreme Court judges are beholden to the rules of the Uniform Court System and the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States. Galison contends that they are. Cahn, Fried and Silbermann contend that they are not.

It must be emphasized that the transcripts in question were NEVER SEALED by Judge Cahn against Galison or anyone else. NOT ONE of the rules regarding sealing of court documents was obeyed. Furthermore, the defense lawyers DO NOT CONTEST the release of the transcripts to Galison. In a letter to judge Silbermann they wrote: “If a transcript of the December 7, 2005 conference with Justice Cahn exists, [we] of course have no objection its being released to the parties”.

The fact that the transcripts exist was made clear by a short portion of the transcripts that Mr. Galison was able to obtain from the court reporter, Myron Calderon. Mr. Calderon told Galison that the entire ex parte meeting was recorded, and that Judge Cahn had “confiscated” most of the record from Calderon before he had a chance to transcribe it.

When Mr. Galison complained to Administrative Judge Silbermann about the confiscation of the transcripts, Judge Cahn immediately recused himself from the case without explanation, against Mr. Galison’s expressed wishes. Even after his recusal however, he has continued to prohibit Mr. Galison from obtaining the transcripts for over two years. When Galison appealed to Judge Silbermann, Silbermann refused to direct Judge Cahn to furnish the transcripts and advised Mr. Galison that his only recourse was to file a formal motion before the judge who replaced Cahn: Bernard Fried, whom Silbermann also personally chose to take over the case. Never in the history of the New York Supreme Court, has a litigant been required to file a motion to obtain an unsealed transcript from the court.

Galison made two formal motions before Fried to obtain the unsealed, uncontested transcripts from his own case. Fried denied the first motion without prejudice, and the second WITH prejudice because, as Judge Fried put it: “I did not give you permission to re-file”. (If a ruling without prejudice cannot be re-filed, how is it difference than a ruling WITH prejudice?)

And so, Mr. Galison has now exhausted all of the available recourses for obtaining the UNSEALED, UNCONTESTED transcripts from his own case. To this day, he does not know why a protective order was placed against him, what evidence was presented and what arguments were made.

Judge Fried then dismissed the entire case in favor of Defense, thereby leaving Galison with no further recourse for obtaining the transcripts. Galison, however is appealing the decision, and hopes that Appellate Court will uphold his fundamental constitutional right to a fair trial.

The ex-parte meeting and the unfair judgment are, unfortunately, commonplace events in the Civil Supreme. What is shocking in this case is the cover up, involving three veteran judges, and their coordinated efforts over two years to deprive a citizen of his basic constitutional rights to obtain the transcripts in his own case.

Mr. Galison has now filed complaints against Judges Cahn, Fried and Silbermann with the Commission on Judicial Conduct.

For more information please contact: William Galison at wgalison@aol.com

Click here to see our previous post on this story.

Monday, January 28, 2008

Integrity Commission Accepts "free" Legal Work From Lobbyists (MORE, CLICK HERE)

GOV-PANEL 'INTEGRITY' CHALLENGED

The New York Post By KENNETH LOVETT

January 28, 2008 -- ALBANY - Four good-government groups want the state Public Integrity Commission to stop accepting free legal work from registered lobbyists under its regulation.

The Post recently reported that Gov. Spitzer's new panel had accepted such freebies from two members of Bryan Cave, a law firm that has lobbied on state real-estate issues, and from a professor at Fordham University, which has its own registered lobbyists.

Citing the Post story, the New York Public Interest Research Group, the state League of Women Voters, Common Cause/New York, and the Citizens Union of the City of New York sent the panel a letter on Jan. 17 calling the practice "inappropriate."

Last week, Executive Director Herbert Teitelbaum, a Fordham adjunct professor and former Bryan Cave partner, responded in a letter that no conflict of interest existed since neither Bryan Cave nor Fordham had any contested or investigatory matters pending before the panel.

The New York Post By KENNETH LOVETT

January 28, 2008 -- ALBANY - Four good-government groups want the state Public Integrity Commission to stop accepting free legal work from registered lobbyists under its regulation.

The Post recently reported that Gov. Spitzer's new panel had accepted such freebies from two members of Bryan Cave, a law firm that has lobbied on state real-estate issues, and from a professor at Fordham University, which has its own registered lobbyists.

Citing the Post story, the New York Public Interest Research Group, the state League of Women Voters, Common Cause/New York, and the Citizens Union of the City of New York sent the panel a letter on Jan. 17 calling the practice "inappropriate."

Last week, Executive Director Herbert Teitelbaum, a Fordham adjunct professor and former Bryan Cave partner, responded in a letter that no conflict of interest existed since neither Bryan Cave nor Fordham had any contested or investigatory matters pending before the panel.

John Grisham on How-To Fix an Election (MORE, CLICK HERE)

If You Can’t Win the Case, Buy an Election and Get Your Own Judge

The New York Times, Books of The Times By JANET MASLIN - January 28, 2008

THE APPEAL By John Grisham (358 pages. Doubleday. $27.95)

“The Appeal” is John Grisham’s handy primer on a timely subject: how to rig an election. Blow by blow, this not-very-fictitious-sounding novel depicts the tactics by which political candidates either can be propelled or ambushed and their campaigns can be subverted. Since so much of what happens here involves legal maneuvering in Mississippi, as have many of his other books, Mr. Grisham knows just how these games are played. He has sadly little trouble making such dirty tricks sound real.

Building a remarkable degree of suspense into the all too familiar ploys described here, Mr. Grisham delivers his savviest book in years. His extended vacation from hard-hitting fiction is over. However passionately he cared about the nonfiction events he described in “An Innocent Man,” his strong suit remains bluntly manipulative, no-frills storytelling, the kind that brings out his great skill as a puppeteer. It barely matters that the characters in “The Appeal” are essentially stick figures. What works for Mr. Grisham is his patient, lawyerly, inexorable way of dramatizing urgent moral issues.

The jumping-off point for “The Appeal” is that a mom-and-pop law firm wins a big Mississippi verdict, triumphing over a chemical company that has spread carcinogenic pollutants. But this victory could turn out to be hollow, because the deep-pocketed corporate defendant isn’t giving up without a fight. The New York-based Krane Chemical swings into combat mode, first by taking stock of these small-town lawyers. The mom and pop are Wes and Mary Grace Payton: nice people, good parents, nearly broke. Krane’s stealth envoys quickly determine that it wouldn’t take much to push the Paytons over the edge.

But the Paytons themselves are little more than a nuisance to Krane. The precedent created by their case is what matters, and the company’s real objective is to make itself safe from similar attacks in the future. In order to arrange that, Krane needs the Mississippi Supreme Court. Another nuisance: Mississippi Supreme Court justices can’t simply be appointed. They have to be elected.

Now the stakes start to ratchet up. So a corrupt senator puts Krane’s greedy billionaire C.E.O., Carl Trudeau, in contact with Troy-Hogan, a mysterious Boca Raton firm that specializes in elections. There is no Troy. There is no Hogan. There is no record of the nature of the business conducted by this privately owned corporation, which is domiciled in Bermuda. For two separate fees, one acknowledged and the other, larger one delivered quietly to an offshore account, Troy-Hogan will do its magic. “When our clients need help,” says Barry Rinehart, Troy-Hogan’s main power player, who radiates the same expensive sartorial confidence that Trudeau does, “we target a Supreme Court justice who is not particularly friendly, and we take him or her out of the picture.”

This multipart process involves choosing a victim and creating rival candidates from scratch. Soon the stealth saboteurs have trained their sights on a justice named Sheila McCarthy. She is not a liberal ideologue, but she can be made to sound like one (“a feminist who’s soft on crime”).

She’s not an operator or a politician. She is unprepared for a campaign fight. And the only special interest group that ever supported her is suddenly a liability. (Anti-McCarthy mailings will trumpet the question “Why Are the Trial Lawyers Financing Sheila McCarthy?”) As Mr. Grisham points out in one of his book’s many moments of indignation, there’s no need for the architects of a smear campaign to answer such a question. All they have to do is keep on asking it.

Meanwhile the covert operators create their own man: Ron Fisk, a political newcomer. “They picked Fisk because he was just old enough to cross their low threshold of legal experience, but still young enough to have ambitions,” the book explains. Fisk is also new enough to be wowed by perks like private jets, which allow him to make so many more campaign stops than his rivals can, and by all the new attention lavished on him by his backers. He barely has time to wonder why they find him so appealing or where all those campaign funds are coming from.

“The Appeal” is clever enough to throw in a rogue third candidate, a clownishly unelectable figure who can draw publicity away from Sheila McCarthy. It also gives her liabilities like a sex life, provides her with an unhelpful zealot as a campaign adviser and underscores the terrible malleability of the voting public. According to a survey cited here, 69 percent of Mississippi’s electorate has no idea that the state’s Supreme Court justices run for office.

And this book has a keen ear for the baloney of biased rhetoric, particularly when it comes from the right. (Mr. Grisham makes no secret of his own political position. He has publicly supported the presidential campaign of Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton.) “Are you aware that Justice Sheila McCarthy is considered the most liberal member of the Mississippi Supreme Court?” a poll inquires. And once the gratuitous issue of gay marriage has been intentionally shoehorned into the campaign, the voice-over on a television ad can be heard asking, “Will liberal judges destroy our families?”

While the election looms, Krane trots out the phrase “junk science” when it appeals the verdict and attacks the expert testimony of a toxicologist, geologist and pathologist, among others who affirmed the effects of Krane’s toxic pollutant. And Ron Fisk, who finds himself giving many of his stump speeches from pulpits, learns to fine-tune his emphases on religion and family values. The extent to which he rails against sin depends on how close he is to the lucrative casinos of the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

“I must say that there is a lot of truth in this story,” Mr. Grisham points out in his author’s note. That point is already unmistakable in his book’s gallingly apt examples and its irrefutable tone. Only when he contrasts the difference between the cynical, venal, jaded rich and their noble, self-sacrificing victims does he court sloppiness and caricature. While the book notes that Wes Payton had to budget for each cup of coffee “and was always looking for quarters,” it presents Carl Trudeau, both stereotypically and ungrammatically, as “a hothead with a massive ego who hated to lose.”

The New York Times, Books of The Times By JANET MASLIN - January 28, 2008

THE APPEAL By John Grisham (358 pages. Doubleday. $27.95)

“The Appeal” is John Grisham’s handy primer on a timely subject: how to rig an election. Blow by blow, this not-very-fictitious-sounding novel depicts the tactics by which political candidates either can be propelled or ambushed and their campaigns can be subverted. Since so much of what happens here involves legal maneuvering in Mississippi, as have many of his other books, Mr. Grisham knows just how these games are played. He has sadly little trouble making such dirty tricks sound real.

Building a remarkable degree of suspense into the all too familiar ploys described here, Mr. Grisham delivers his savviest book in years. His extended vacation from hard-hitting fiction is over. However passionately he cared about the nonfiction events he described in “An Innocent Man,” his strong suit remains bluntly manipulative, no-frills storytelling, the kind that brings out his great skill as a puppeteer. It barely matters that the characters in “The Appeal” are essentially stick figures. What works for Mr. Grisham is his patient, lawyerly, inexorable way of dramatizing urgent moral issues.

The jumping-off point for “The Appeal” is that a mom-and-pop law firm wins a big Mississippi verdict, triumphing over a chemical company that has spread carcinogenic pollutants. But this victory could turn out to be hollow, because the deep-pocketed corporate defendant isn’t giving up without a fight. The New York-based Krane Chemical swings into combat mode, first by taking stock of these small-town lawyers. The mom and pop are Wes and Mary Grace Payton: nice people, good parents, nearly broke. Krane’s stealth envoys quickly determine that it wouldn’t take much to push the Paytons over the edge.

But the Paytons themselves are little more than a nuisance to Krane. The precedent created by their case is what matters, and the company’s real objective is to make itself safe from similar attacks in the future. In order to arrange that, Krane needs the Mississippi Supreme Court. Another nuisance: Mississippi Supreme Court justices can’t simply be appointed. They have to be elected.

Now the stakes start to ratchet up. So a corrupt senator puts Krane’s greedy billionaire C.E.O., Carl Trudeau, in contact with Troy-Hogan, a mysterious Boca Raton firm that specializes in elections. There is no Troy. There is no Hogan. There is no record of the nature of the business conducted by this privately owned corporation, which is domiciled in Bermuda. For two separate fees, one acknowledged and the other, larger one delivered quietly to an offshore account, Troy-Hogan will do its magic. “When our clients need help,” says Barry Rinehart, Troy-Hogan’s main power player, who radiates the same expensive sartorial confidence that Trudeau does, “we target a Supreme Court justice who is not particularly friendly, and we take him or her out of the picture.”

This multipart process involves choosing a victim and creating rival candidates from scratch. Soon the stealth saboteurs have trained their sights on a justice named Sheila McCarthy. She is not a liberal ideologue, but she can be made to sound like one (“a feminist who’s soft on crime”).

She’s not an operator or a politician. She is unprepared for a campaign fight. And the only special interest group that ever supported her is suddenly a liability. (Anti-McCarthy mailings will trumpet the question “Why Are the Trial Lawyers Financing Sheila McCarthy?”) As Mr. Grisham points out in one of his book’s many moments of indignation, there’s no need for the architects of a smear campaign to answer such a question. All they have to do is keep on asking it.

Meanwhile the covert operators create their own man: Ron Fisk, a political newcomer. “They picked Fisk because he was just old enough to cross their low threshold of legal experience, but still young enough to have ambitions,” the book explains. Fisk is also new enough to be wowed by perks like private jets, which allow him to make so many more campaign stops than his rivals can, and by all the new attention lavished on him by his backers. He barely has time to wonder why they find him so appealing or where all those campaign funds are coming from.

“The Appeal” is clever enough to throw in a rogue third candidate, a clownishly unelectable figure who can draw publicity away from Sheila McCarthy. It also gives her liabilities like a sex life, provides her with an unhelpful zealot as a campaign adviser and underscores the terrible malleability of the voting public. According to a survey cited here, 69 percent of Mississippi’s electorate has no idea that the state’s Supreme Court justices run for office.

And this book has a keen ear for the baloney of biased rhetoric, particularly when it comes from the right. (Mr. Grisham makes no secret of his own political position. He has publicly supported the presidential campaign of Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton.) “Are you aware that Justice Sheila McCarthy is considered the most liberal member of the Mississippi Supreme Court?” a poll inquires. And once the gratuitous issue of gay marriage has been intentionally shoehorned into the campaign, the voice-over on a television ad can be heard asking, “Will liberal judges destroy our families?”

While the election looms, Krane trots out the phrase “junk science” when it appeals the verdict and attacks the expert testimony of a toxicologist, geologist and pathologist, among others who affirmed the effects of Krane’s toxic pollutant. And Ron Fisk, who finds himself giving many of his stump speeches from pulpits, learns to fine-tune his emphases on religion and family values. The extent to which he rails against sin depends on how close he is to the lucrative casinos of the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

“I must say that there is a lot of truth in this story,” Mr. Grisham points out in his author’s note. That point is already unmistakable in his book’s gallingly apt examples and its irrefutable tone. Only when he contrasts the difference between the cynical, venal, jaded rich and their noble, self-sacrificing victims does he court sloppiness and caricature. While the book notes that Wes Payton had to budget for each cup of coffee “and was always looking for quarters,” it presents Carl Trudeau, both stereotypically and ungrammatically, as “a hothead with a massive ego who hated to lose.”

Sunday, January 27, 2008

Judge Napolitano: A Judicial Surprise (MORE, CLICK HERE)

A Judicial Surprise

New York Sun OPINION

New York Sun OPINION

By ANDREW NAPOLITANO - January 25, 2008

While New Yorkers were preoccupied with the stock market slide, the Giants in the playoffs, and the presidential primaries, the United States Supreme Court was studying the Constitution of the State of New York and examining the manner in which it permits politicians to select judicial nominees. And it did not like what it found.

Here's the background. Judge Margarita Lopez Torres was elected to a four-year term on the Civil Court in the Bronx in 1992. She was nominated to that position by the Democratic Party through a direct primary election.

Shortly after assuming her job, party leaders began to demand that she make patronage hires, demands to which she says she could not acquiesce since doing so would be inconsistent with being a member of an independent judiciary.

The party bosses wanted Judge Lopez Torres to hire their friends and political hacks in various courthouse positions, full-time and part-time, as sort of a payback to them for assuring that she would continue to receive the Democratic nomination for Civil Court judge.

Judge Lopez Torres, who by many accounts has served admirably and well, desired promotion to the Supreme Court of the State of New York which, despite its name, is the basic trial court of general jurisdiction, but is still superior in jurisdiction, authority, prestige, and pay to the Civil Court.

To become a Supreme Court justice in the State of New York, one either needs to be promoted from the Civil Court and then elected to a 14-year term or one needs to be elected directly to a 14-year term. To be elected, one needs to have one's name on the ballot, and to get on the ballot one needs the imprimatur of a nominating convention of one of the major political parties in New York.

Judge Lopez Torres quickly learned that her decision to reject the patronage hires requested of her by Democratic party bosses meant she could never receive a judicial nomination from them, and, without the nomination, would never become a justice of the Supreme Court of the State of New York. So, she sued the bosses.

She and several registered voters who wanted to vote for her but could not filed a complaint in federal court, and in the initial round persuaded a judge to invalidate the state's nominating system. The Court found that the New York system which permits party conventions (read, party regulars controlled by party bosses), rather than voters, to decide who becomes a judicial nominee effectively denies voters the right to choose a nominee and forces potential nominees to play ball with party bosses. The decision invalidating the New York system was upheld unanimously by a 3-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit. The bosses appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

What happened thereafter was a surprise to everyone involved. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for a unanimous Supreme Court, utilized something we rarely see in appellate judges today: The principle of judicial restraint.

Even though the Court did not like the New York system, even though it doesn't always produce better judges, even though Judge Lopez Torres was a good judge who should be able to present her case to the voters without having to hire people whom the party bosses want her to hire, the United States Supreme Court let stand the New York State Supreme Court system for choosing judicial nominees.

Judge Lopez Torres argued that the New York system violated her First Amendment rights by forcing her to use words indicating approval of the bosses whom she disrespected and by compelling her to associate with them. Not only does the First Amendment — "Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech … or the right of the people peaceably to assemble … " — prohibit Congress and the States from punishing speech or assembly, it also prohibits them from compelling speech or assembly.

The government cannot punish speech or silence, and it cannot prohibit associating with others or compel any associations. But the United States Supreme Court would hear none of this. Judge Lopez Torres chose to enter the system. No one forced her. And political parties as we know them, the Court held, would not exist if they could not command loyalty and exclude those who disagree. What about counties like Manhattan with one party rule? The party must be doing something right in those counties, Justice Scalia wrote, or the voters would not tolerate it.

The Supreme Court decision brought together judicial minds as disparate as Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Clarence Thomas to agree on the principle that the federal courts, as Justice Felix Frankfurter once famously wrote, do not exist in order to right every wrong. All Judge Lopez Torres wanted was access to the ballot: The right to have voters say yea or nay to her. The members of the Court to a person thought she should have that right, but found nothing in the Constitution guaranteeing it. Do laws that let party bosses choose our judges serve the people's best interests? Of course not. Do laws that let them pick who they want to serve for the people's best interests? Not according to the nine appointed life-tenured justices of the United States Supreme Court. Will federal courts remedy this? No, because as Justice Thurgood Marshall liked to say "[t]he Constitution does not prohibit [state] legislatures from enacting stupid laws."

So, we in New York remain subject to party bosses and all their whims and deals and chicanery in choosing our judges. This is surely patently unwise, but it is not unconstitutional.

Judge Napolitano, who was on the bench of the Superior Court of New Jersey between 1987 and 1995, is the senior judicial analyst at the Fox News Channel. His latest book is "A Nation of Sheep" (Nelson, 2007).

While New Yorkers were preoccupied with the stock market slide, the Giants in the playoffs, and the presidential primaries, the United States Supreme Court was studying the Constitution of the State of New York and examining the manner in which it permits politicians to select judicial nominees. And it did not like what it found.

Here's the background. Judge Margarita Lopez Torres was elected to a four-year term on the Civil Court in the Bronx in 1992. She was nominated to that position by the Democratic Party through a direct primary election.

Shortly after assuming her job, party leaders began to demand that she make patronage hires, demands to which she says she could not acquiesce since doing so would be inconsistent with being a member of an independent judiciary.

The party bosses wanted Judge Lopez Torres to hire their friends and political hacks in various courthouse positions, full-time and part-time, as sort of a payback to them for assuring that she would continue to receive the Democratic nomination for Civil Court judge.

Judge Lopez Torres, who by many accounts has served admirably and well, desired promotion to the Supreme Court of the State of New York which, despite its name, is the basic trial court of general jurisdiction, but is still superior in jurisdiction, authority, prestige, and pay to the Civil Court.

To become a Supreme Court justice in the State of New York, one either needs to be promoted from the Civil Court and then elected to a 14-year term or one needs to be elected directly to a 14-year term. To be elected, one needs to have one's name on the ballot, and to get on the ballot one needs the imprimatur of a nominating convention of one of the major political parties in New York.

Judge Lopez Torres quickly learned that her decision to reject the patronage hires requested of her by Democratic party bosses meant she could never receive a judicial nomination from them, and, without the nomination, would never become a justice of the Supreme Court of the State of New York. So, she sued the bosses.

She and several registered voters who wanted to vote for her but could not filed a complaint in federal court, and in the initial round persuaded a judge to invalidate the state's nominating system. The Court found that the New York system which permits party conventions (read, party regulars controlled by party bosses), rather than voters, to decide who becomes a judicial nominee effectively denies voters the right to choose a nominee and forces potential nominees to play ball with party bosses. The decision invalidating the New York system was upheld unanimously by a 3-judge panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit. The bosses appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

What happened thereafter was a surprise to everyone involved. Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for a unanimous Supreme Court, utilized something we rarely see in appellate judges today: The principle of judicial restraint.

Even though the Court did not like the New York system, even though it doesn't always produce better judges, even though Judge Lopez Torres was a good judge who should be able to present her case to the voters without having to hire people whom the party bosses want her to hire, the United States Supreme Court let stand the New York State Supreme Court system for choosing judicial nominees.

Judge Lopez Torres argued that the New York system violated her First Amendment rights by forcing her to use words indicating approval of the bosses whom she disrespected and by compelling her to associate with them. Not only does the First Amendment — "Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech … or the right of the people peaceably to assemble … " — prohibit Congress and the States from punishing speech or assembly, it also prohibits them from compelling speech or assembly.

The government cannot punish speech or silence, and it cannot prohibit associating with others or compel any associations. But the United States Supreme Court would hear none of this. Judge Lopez Torres chose to enter the system. No one forced her. And political parties as we know them, the Court held, would not exist if they could not command loyalty and exclude those who disagree. What about counties like Manhattan with one party rule? The party must be doing something right in those counties, Justice Scalia wrote, or the voters would not tolerate it.

The Supreme Court decision brought together judicial minds as disparate as Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Clarence Thomas to agree on the principle that the federal courts, as Justice Felix Frankfurter once famously wrote, do not exist in order to right every wrong. All Judge Lopez Torres wanted was access to the ballot: The right to have voters say yea or nay to her. The members of the Court to a person thought she should have that right, but found nothing in the Constitution guaranteeing it. Do laws that let party bosses choose our judges serve the people's best interests? Of course not. Do laws that let them pick who they want to serve for the people's best interests? Not according to the nine appointed life-tenured justices of the United States Supreme Court. Will federal courts remedy this? No, because as Justice Thurgood Marshall liked to say "[t]he Constitution does not prohibit [state] legislatures from enacting stupid laws."

So, we in New York remain subject to party bosses and all their whims and deals and chicanery in choosing our judges. This is surely patently unwise, but it is not unconstitutional.

Judge Napolitano, who was on the bench of the Superior Court of New Jersey between 1987 and 1995, is the senior judicial analyst at the Fox News Channel. His latest book is "A Nation of Sheep" (Nelson, 2007).

New York Sun: Judge Brennan rolling in his grave (MORE, CLICK HERE)

Light 'Em Up

New York Sun Editorial - January 17, 2008

Justice Brennan must be rolling in his grave. The center at New York University that bears his name took a First Amendment case about political cronyism in Brooklyn all the way to the Supreme Court and couldn't get a single vote. Not a one. Not even a twitch of the bow tie of Justice Stevens, with whom Justice Brennan sat on the bench for 15 years, or a ruffle from a First Amendment absolutist like Justice Scalia, or a swing voter like Justice Kennedy, who also, albeit for a shorter time, shared the high bench with Brennan.

At issue in the case was how New York State picks judges for its state Supreme Court. New York courts are famously confusing. Here's an example: the top court is the Court of Appeals, where the members of the bench prefer to be addressed as "judge." Two levels below is the State Supreme Court, which despite its fancy name, is the basic trial court. The several hundred jurists on that court like to be called "justice."

About the only thing more confusing is how Supreme Court justices are selected. The last stage of the process is Election Day, when voters go to the polls and elect the judges. In New York City at least, the candidates put up by the Democratic Party will almost always get elected. So the trick to getting to the bench is getting that nomination.

There isn't any primary. Instead there is something called a judicial nominating convention, attended by several dozen party delegates. These conventions aren't the model of democracy. In practice, the candidate who has the support of the party boss, like Assemblyman Vito Lopez in Brooklyn or Assemblyman Herman "Denny" Farrell in Manhattan, is almost always the person who gets to be judge. In other words, judge-making is the last true vestige of the old patronage system left to county bosses.

One lower court judge, Margarita Lopez Torres, with the backing of the Brennan Center, challenged the whole system. As a civil court judge, Ms. Lopez Torres had sought a spot on the state Supreme Court bench, but never could get the support of Mr. Lopez's predecessor, Clarence Norman, Jr., who, by the way, is now in prison on corruption charges. The editors of these pages are great admirers of Ms. Lopez Torres and sympathetic to others who find themselves on the fringes of the party system. But, as we indicated October 3 in our editorial "Lopez-Torres Before the Nine," we didn't have much sympathy with her case. She could have run as an independent. We had a similar feeling when Mayor Bloomberg tried to institute in city politics a system of "non-partisan" elections.

* * *

And it is something for the country to think about as the great political parties thrash their way through trying to choose by a vast, monumentally expensive primary system, candidates who for years were chosen in smoke-filled rooms of party conventions. If the parties start to think about reforming the vast circus and returning to the convention system (as R. Emmett Tyrrell suggests nearby), they will find their standing buttressed by the decision of all nine justices of the Supreme Court in Lopez Torres. "A political party," the justices said, "has a First Amendment right to limit its membership as it wishes, and to choose a candidate selection process that will in its view produce the nominee who best represents its political platform." And The Great Scalia, writing for the majority, said that what might constitute a "fair shot" at a nomination is a reasonable question for a legislature, but not for judges, and went on to say: "Party conventions, with their attendant 'smoke-filled rooms' and domination by party leaders, have long been an accepted manner of selecting party candidates." To which we can only add, "light 'em up."

New York Sun Editorial - January 17, 2008

Justice Brennan must be rolling in his grave. The center at New York University that bears his name took a First Amendment case about political cronyism in Brooklyn all the way to the Supreme Court and couldn't get a single vote. Not a one. Not even a twitch of the bow tie of Justice Stevens, with whom Justice Brennan sat on the bench for 15 years, or a ruffle from a First Amendment absolutist like Justice Scalia, or a swing voter like Justice Kennedy, who also, albeit for a shorter time, shared the high bench with Brennan.

At issue in the case was how New York State picks judges for its state Supreme Court. New York courts are famously confusing. Here's an example: the top court is the Court of Appeals, where the members of the bench prefer to be addressed as "judge." Two levels below is the State Supreme Court, which despite its fancy name, is the basic trial court. The several hundred jurists on that court like to be called "justice."

About the only thing more confusing is how Supreme Court justices are selected. The last stage of the process is Election Day, when voters go to the polls and elect the judges. In New York City at least, the candidates put up by the Democratic Party will almost always get elected. So the trick to getting to the bench is getting that nomination.

There isn't any primary. Instead there is something called a judicial nominating convention, attended by several dozen party delegates. These conventions aren't the model of democracy. In practice, the candidate who has the support of the party boss, like Assemblyman Vito Lopez in Brooklyn or Assemblyman Herman "Denny" Farrell in Manhattan, is almost always the person who gets to be judge. In other words, judge-making is the last true vestige of the old patronage system left to county bosses.

One lower court judge, Margarita Lopez Torres, with the backing of the Brennan Center, challenged the whole system. As a civil court judge, Ms. Lopez Torres had sought a spot on the state Supreme Court bench, but never could get the support of Mr. Lopez's predecessor, Clarence Norman, Jr., who, by the way, is now in prison on corruption charges. The editors of these pages are great admirers of Ms. Lopez Torres and sympathetic to others who find themselves on the fringes of the party system. But, as we indicated October 3 in our editorial "Lopez-Torres Before the Nine," we didn't have much sympathy with her case. She could have run as an independent. We had a similar feeling when Mayor Bloomberg tried to institute in city politics a system of "non-partisan" elections.

* * *

And it is something for the country to think about as the great political parties thrash their way through trying to choose by a vast, monumentally expensive primary system, candidates who for years were chosen in smoke-filled rooms of party conventions. If the parties start to think about reforming the vast circus and returning to the convention system (as R. Emmett Tyrrell suggests nearby), they will find their standing buttressed by the decision of all nine justices of the Supreme Court in Lopez Torres. "A political party," the justices said, "has a First Amendment right to limit its membership as it wishes, and to choose a candidate selection process that will in its view produce the nominee who best represents its political platform." And The Great Scalia, writing for the majority, said that what might constitute a "fair shot" at a nomination is a reasonable question for a legislature, but not for judges, and went on to say: "Party conventions, with their attendant 'smoke-filled rooms' and domination by party leaders, have long been an accepted manner of selecting party candidates." To which we can only add, "light 'em up."

Saturday, January 26, 2008

Kerik Federal Judge Shines Light on Attorney Misconduct (MORE, CLICK HERE)

NY BigLaw Lawyer Ousted From Kerik Case; Will Likely Be Called as Witness Against Client

By Mark Hamblett

New York Law Journal/New York Lawyer - January 25, 2008

A federal judge has ordered the attorney of ex-New York Police Commissioner Bernard Kerik off the case for an actual conflict of interest.

As a result, Kenneth Breen, a partner at Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker, will no longer be able to defend Mr. Kerik against a 16-count indictment that includes charges of accepting payments from a company that sought to do business with New York City, tax fraud, making false statements to the federal government and providing false information on a loan application.

Southern District Judge Stephen Robinson based his decision on the virtual certainty that Mr. Breen would be called as a witness in United States v. Kerik, 07 Cr. 1027.

"The conflict in this case is so severe that no remedial measure will cure it," the judge said as he discussed the allegedly misleading statements Mr. Kerik made to Mr. Breen and defense attorney Joseph Tacopina that had been passed on to investigators.

"Even if Mr. Breen were not to become an actual witness, he would be an unsworn witness who could subtly impart to the jury his first-hand knowledge of events without having to swear an oath or be subject to cross-examination," Judge Robinson said. "For defense counsel, becoming an unsworn witness, standing alone, is sufficient for disqualification."

Mr. Breen said yesterday that Mr. Kerik is disappointed with the decision and is reviewing his options.

In 2004, Mr. Kerik withdrew his nomination as Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security after he admitted he had not paid taxes on the wages he paid his children's nanny. Soon after, Mr. Kerik became the target of accusations about personal, ethical and financial improprieties, including accepting renovations to his Bronx apartment from a company that was seeking city contracts.

Mr. Tacopina, Mr. Kerik's then-defense attorney who later withdrew from the case for reasons unstated, met with the Bronx district attorney following Mr. Kerik's resignation as police commissioner.

Mr. Tacopina told prosecutors that Mr. Kerik had paid for the renovations to his Riverdale apartment himself and a Manhattan Realtor had given him a loan for a down payment on the apartment, a loan Mr. Kerik had repaid in 2003.

Mr. Kerik pleaded guilty to two misdemeanors in the Bronx case in June 2006, admitting he failed to report a loan and that he accepted $165,000 in renovations to the apartment. He was fined $221,000.

Prosecutors with the Southern District U.S. Attorney's Office questioned Mr. Tacopina on his statements about the renovations and loan. Mr. Tacopina confirmed first that he had made the statements and second, that he had received the information from Mr. Kerik for the "express purpose" of conveying it to Bronx prosecutors.

As the federal investigation proceeded, Southern District prosecutors also met with a deputy commissioner of the New York City Department of Investigation, who reported being told by Mr. Tacopina that the Kerik apartment renovations cost between $30,000 and $50,000 and no one else had paid for them. Again, Mr. Tacopina confirmed making the statements for the express purpose of informing the Department of Investigation.

The statements made to the Bronx district attorney and the Department of Investigations were the basis for some of the federal charges later levied against Mr. Kerik.

Mr. Breen joined the Kerik defense team in 2005 and Mr. Tacopina told investigators over the course of the following year that Mr. Kerik repeated those statements to both himself and Mr. Breen. Mr. Tacopina left the case before the 2007 federal indictment.

Mr. Breen filed a brief in opposition his disqualification. James D. Wareham, also of Paul Hastings, represented him at the oral arguments before Judge Robinson.

Arguments Rejected

Assistant U.S. Attorneys Perry A. Carbone and Elliott B. Jacobson told the court that Mr. Kerik was informed of the conflict more than seven months before his indictment.

After his indictment, Mr. Kerik argued that the alleged conflict was merely hypothetical and that, in any event, the conflict was waivable. He also claimed the statements were privileged and protected by Federal Rule of Evidence 410 because they were made in the course of plea negotiations.

And even if they were not protected by Rule 401, he argued, admission of the statements would deprive him of his Sixth Amendment right to counsel.

Mr. Kerik said Mr. Breen's role was limited and that Mr. Tacopina was the one who took the lead on what he claimed were plea discussions.

"Unfortunately for the defendant," Judge Robinson said in his ruling, "this type of potential disagreement or nuance to the discussions at issue is exactly the kind of argument that could necessitate Mr. Breen's testimony at trial."

Mr. Kerik tried to argue that he was not challenging his plea allocution in the Bronx but was instead reserving the right to challenge the government's interpretation of that allocution.

"This argument misses the point," Judge Robinson said. "It is not the truth of Mr. Kerik's plea allocution that is questioned here. The issue is whether in discussions prior to his plea Mr. Kerik authorized his attorneys, including Mr. Breen, to relay statements . . . that were misleading and obstructive."

Mr. Breen's potential testimony, the judge said, "is direct evidence of the charges contained in the indictment."

The judge said it was likely that Mr. Kerik will "disagree with and heavily cross-examine Mr. Tacopina regarding the alleged authorization by the defendant as well as the substance of any discussions."

Mr. Breen may have to be called to corroborate or dispute those accounts, he said, and should he disagree with Mr. Tacopina's recollections, Mr. Breen "will either be forced to sit quietly in detriment to his client or (without taking an oath or being cross-examined) to ask questions to which the jury might assign undue weight."

Judge Robinson rejected the rest of Mr. Kerik's arguments.

Even if the statements were privileged and the privilege has not been waived, he said, "the statements would still be admissible under the crime-fraud exception, even where, as here, the attorney was not a knowing participant in the crime or fraud in question."

By Mark Hamblett

New York Law Journal/New York Lawyer - January 25, 2008

A federal judge has ordered the attorney of ex-New York Police Commissioner Bernard Kerik off the case for an actual conflict of interest.

As a result, Kenneth Breen, a partner at Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker, will no longer be able to defend Mr. Kerik against a 16-count indictment that includes charges of accepting payments from a company that sought to do business with New York City, tax fraud, making false statements to the federal government and providing false information on a loan application.

Southern District Judge Stephen Robinson based his decision on the virtual certainty that Mr. Breen would be called as a witness in United States v. Kerik, 07 Cr. 1027.

"The conflict in this case is so severe that no remedial measure will cure it," the judge said as he discussed the allegedly misleading statements Mr. Kerik made to Mr. Breen and defense attorney Joseph Tacopina that had been passed on to investigators.

"Even if Mr. Breen were not to become an actual witness, he would be an unsworn witness who could subtly impart to the jury his first-hand knowledge of events without having to swear an oath or be subject to cross-examination," Judge Robinson said. "For defense counsel, becoming an unsworn witness, standing alone, is sufficient for disqualification."

Mr. Breen said yesterday that Mr. Kerik is disappointed with the decision and is reviewing his options.

In 2004, Mr. Kerik withdrew his nomination as Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security after he admitted he had not paid taxes on the wages he paid his children's nanny. Soon after, Mr. Kerik became the target of accusations about personal, ethical and financial improprieties, including accepting renovations to his Bronx apartment from a company that was seeking city contracts.

Mr. Tacopina, Mr. Kerik's then-defense attorney who later withdrew from the case for reasons unstated, met with the Bronx district attorney following Mr. Kerik's resignation as police commissioner.

Mr. Tacopina told prosecutors that Mr. Kerik had paid for the renovations to his Riverdale apartment himself and a Manhattan Realtor had given him a loan for a down payment on the apartment, a loan Mr. Kerik had repaid in 2003.

Mr. Kerik pleaded guilty to two misdemeanors in the Bronx case in June 2006, admitting he failed to report a loan and that he accepted $165,000 in renovations to the apartment. He was fined $221,000.

Prosecutors with the Southern District U.S. Attorney's Office questioned Mr. Tacopina on his statements about the renovations and loan. Mr. Tacopina confirmed first that he had made the statements and second, that he had received the information from Mr. Kerik for the "express purpose" of conveying it to Bronx prosecutors.

As the federal investigation proceeded, Southern District prosecutors also met with a deputy commissioner of the New York City Department of Investigation, who reported being told by Mr. Tacopina that the Kerik apartment renovations cost between $30,000 and $50,000 and no one else had paid for them. Again, Mr. Tacopina confirmed making the statements for the express purpose of informing the Department of Investigation.

The statements made to the Bronx district attorney and the Department of Investigations were the basis for some of the federal charges later levied against Mr. Kerik.

Mr. Breen joined the Kerik defense team in 2005 and Mr. Tacopina told investigators over the course of the following year that Mr. Kerik repeated those statements to both himself and Mr. Breen. Mr. Tacopina left the case before the 2007 federal indictment.

Mr. Breen filed a brief in opposition his disqualification. James D. Wareham, also of Paul Hastings, represented him at the oral arguments before Judge Robinson.

Arguments Rejected

Assistant U.S. Attorneys Perry A. Carbone and Elliott B. Jacobson told the court that Mr. Kerik was informed of the conflict more than seven months before his indictment.

After his indictment, Mr. Kerik argued that the alleged conflict was merely hypothetical and that, in any event, the conflict was waivable. He also claimed the statements were privileged and protected by Federal Rule of Evidence 410 because they were made in the course of plea negotiations.

And even if they were not protected by Rule 401, he argued, admission of the statements would deprive him of his Sixth Amendment right to counsel.

Mr. Kerik said Mr. Breen's role was limited and that Mr. Tacopina was the one who took the lead on what he claimed were plea discussions.

"Unfortunately for the defendant," Judge Robinson said in his ruling, "this type of potential disagreement or nuance to the discussions at issue is exactly the kind of argument that could necessitate Mr. Breen's testimony at trial."

Mr. Kerik tried to argue that he was not challenging his plea allocution in the Bronx but was instead reserving the right to challenge the government's interpretation of that allocution.

"This argument misses the point," Judge Robinson said. "It is not the truth of Mr. Kerik's plea allocution that is questioned here. The issue is whether in discussions prior to his plea Mr. Kerik authorized his attorneys, including Mr. Breen, to relay statements . . . that were misleading and obstructive."

Mr. Breen's potential testimony, the judge said, "is direct evidence of the charges contained in the indictment."

The judge said it was likely that Mr. Kerik will "disagree with and heavily cross-examine Mr. Tacopina regarding the alleged authorization by the defendant as well as the substance of any discussions."

Mr. Breen may have to be called to corroborate or dispute those accounts, he said, and should he disagree with Mr. Tacopina's recollections, Mr. Breen "will either be forced to sit quietly in detriment to his client or (without taking an oath or being cross-examined) to ask questions to which the jury might assign undue weight."

Judge Robinson rejected the rest of Mr. Kerik's arguments.

Even if the statements were privileged and the privilege has not been waived, he said, "the statements would still be admissible under the crime-fraud exception, even where, as here, the attorney was not a knowing participant in the crime or fraud in question."

Wednesday, January 23, 2008

More Mississippi Mud on Scruggs' Judicial Fixin' (MORE, CLICK HERE)

The Legal Trail in a Delta Drama

The New York Times By NELSON D. SCHWARTZ - January 20, 2008