The Washington Post by Robert Barnes - March 2, 2009

W.Va. Justice Ruled for a Man Who Spent Millions to Elect Him

BECKLEY, W.Va. -- Hugh Caperton was born into the coal business, but for more than a decade he has spent more time in a courthouse than in a mine. The complex, intrigue-filled legal tale he will present to the Supreme Court this week was literally enough to spawn a suspense novel, but it boils down to this: Caperton and his little coal company sued a huge coal company on claims that it unlawfully drove him out of business, and a jury agreed, awarding him $50 million. That company's chief executive vowed an appeal to the West Virginia Supreme Court -- but first, he spent an unprecedented $3 million to persuade voters to get rid of a justice he didn't like and elect one he did.

That justice provided the decisive vote in overturning Caperton's multimillion-dollar award. And the case raises profound questions about the way Americans elect their judges, the duty of judges to recuse themselves when the people who bankrolled their campaigns come before them and, even, the very meaning of judicial impartiality. The facts are so compelling that John Grisham used them as a basis for his bestseller "The Appeal." On opposing sides during oral arguments Tuesday will be two of the court's most prolific and persuasive practitioners, former solicitor general Theodore B. Olson and Andrew L. Frey.

But the implications go far beyond West Virginia, energizing critics of the multimillion-dollar political campaigns that are now the norm in many of the 39 states that elect judges, where no-holds-barred television advertising has replaced the staid and polite debates of the past. Among the outpouring of supporters for Caperton are a number of unlikely compatriots -- Wal-Mart siding with the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law, for instance. "It's about the fundamental responsibility of the judiciary: a fair hearing before an impartial arbiter," said James Sample of the Brennan Center. "This is a fact-bound, multi-factor, worst-of-the-worst scenario; if any sort of floor exists for due process, this is the best case to plumb those depths."

But the facts, according to Caperton's nemesis, Don Blankenship, chief executive of A.T. Massey Coal Co., are these: Blankenship made lawful contributions to and on behalf of now-Justice Brent Benjamin. As in other political causes he has supported, he has a right to his political views about who is best to serve on the West Virginia Supreme Court. And there is no evidence that Benjamin had anything to gain financially from the dispute between Caperton and Blankenship, the only reason for recusal the Supreme Court until now has recognized. Blankenship attorney Frey, in his brief to the court, rejects arguments from Caperton that Benjamin had an obligation to recuse himself because of bias or "the probability of bias" or because he owed Blankenship a "debt of gratitude." "Such a theory . . . would have no limiting principle, would be entirely unworkable and would create serious administrative problems for courts," Frey wrote.

He spins an intriguing set of conflicts. Should a judge sit on a case involving a newspaper that endorsed his campaign? Is recusal necessary when one party is an interest group that worked for the judge's election? If the justice Blankenship worked so hard to oust had been reelected, would he harbor such animus that he should recuse himself from the case? "If 'probability of bias' were the constitutional standard," Frey wrote to the justices, "many members of this court would quite likely have been acting unconstitutionally by participating in numerous cases decided over the past 200 years." Caperton attorney Olson dismisses such a "slippery-slope/parade-of-horrible argument" as a distraction. "The thing I ask people is: 'If you had an important case coming up and your opponent gave $3 million to elect the judge who was going to decide it, would you think that was fair?'" Olson said. "I haven't met a person yet who thinks that's fair."

Caperton said that certainly was his thought in 2006, the first time he entered the ornate chambers of the West Virginia Supreme Court. His legal battles had been largely successful to that point, despite what he said was an early warning from Blankenship. "He said, 'I spend a million dollars a month on attorneys, and I'll tie you up for years in court,' " Caperton said. " 'Every expert you get, I'll find three.' " Blankenship and Benjamin declined to be interviewed. Nevertheless, Caperton convinced juries in Virginia and West Virginia that Massey Coal's business tactics -- including buying Caperton's coal purchaser and canceling contracts -- had unlawfully driven Caperton out of business. Blankenship appealed to the West Virginia high court, but not before he got heavily involved in its 2004 elections. Although he gave only the allowed maximum $1,000 to Benjamin's campaign, he formed a political fundraising organization to "beat Warren McGraw," a longtime state politician and justice who was up for reelection and would be Benjamin's opponent.

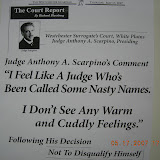

The $3 million Blankenship spent on the race was more than all of Benjamin's other contributors combined. Blankenship and business groups supported Benjamin, labor unions and defense lawyers supported McGraw, and the result was one of the nastiest races in state history. "I'd been in some of the meanest campaigns in West Virginia," said McGraw, who has served in many state political offices and is now a judge in tiny Pineville. "But this campaign for the Supreme Court was without honor." Though Blankenship's dispute with Caperton was in the background of the race, the ads portrayed McGraw as voting to release a child molester: "Letting a child rapist go free? To work in our schools? That's radical Justice Warren McGraw." Benjamin, the first non-incumbent Republican elected to the court since the 1920s, declined to recuse himself when Blankenship's appeal reached the court. "No objective information is advanced to show that this justice has a bias for or against any litigant . . . or that this justice will be anything but fair and impartial," he wrote.

So when Caperton entered the court that day and looked at the five justices who would decide his case, he saw one whose campaign was financed by Blankenship and another rumored to be one of Blankenship's best friends. "I'm not thinking due process and I'm not thinking 14th Amendment; as a citizen I'm sitting there saying, 'How in the world? I've got two votes against me and we haven't even started yet,' " Caperton said. The court reversed the award, 3 to 2, saying among other things that the suit was not filed in the proper jurisdiction. But that was only the beginning of what became something of a meltdown on the West Virginia Supreme Court. Caperton's attorney received photos of Blankenship and Justice Elliott "Spike" Maynard, the one with whom he was rumored to be friendly, at a dinner on vacation on the French Riviera. And Justice Larry Starcher was quoted in the New York Times saying Blankenship's bankrolling of Benjamin's campaign made him want to "puke."

A rehearing was scheduled, with two circuit judges taking the places of Maynard and Starcher. The vote again was 3-2, with Benjamin again casting the decisive vote. "I just want a hearing in front of an impartial court of justices," Caperton said, and his petition asks for a remand to the West Virginia Supreme Court, without Benjamin. Caperton has drawn lopsided support in the case from legal and business groups, as well as those who worry about the role money now plays in judicial elections. Wal-Mart joined with Lockheed Martin, Pepsi and other corporations on Caperton's side, telling the court in a brief that requiring Benjamin's recusal "would signal to businesses and the general public that judicial decisions cannot be bought and sold."

Justice at Stake, a judicial reform group that has been sounding the alarm about the role of money in judges' races, notes that the amount of money raised by state supreme court candidates from 2000 to 2007 was almost $168 million, nearly double that raised during the 1990s. Former Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O'Connor is among those sharply critical of those elections. The Justice at Stake brief, joined by Common Cause, the League of Women Voters and a host of others, warns the court that it would "weaken state reform efforts" to find no "constitutionally significant threat to equal justice" in the case. Frey said the real goal of those lined up against his client is their desire that judges be appointed, not elected. "I'm no fan of judicial elections either, but it's not the job of the Supreme Court" to decide that, Frey said. The other side, Frey said, would erase the "presumption that a judge really will be impartial." And he said that in all the briefs filed on behalf of his opponent, no one proposes a clear line for what level of support -- be it financial or editorial or even gratitude to the chief executive who appointed a judge -- to call that presumption of impartiality into question.

BECKLEY, W.Va. -- Hugh Caperton was born into the coal business, but for more than a decade he has spent more time in a courthouse than in a mine. The complex, intrigue-filled legal tale he will present to the Supreme Court this week was literally enough to spawn a suspense novel, but it boils down to this: Caperton and his little coal company sued a huge coal company on claims that it unlawfully drove him out of business, and a jury agreed, awarding him $50 million. That company's chief executive vowed an appeal to the West Virginia Supreme Court -- but first, he spent an unprecedented $3 million to persuade voters to get rid of a justice he didn't like and elect one he did.

That justice provided the decisive vote in overturning Caperton's multimillion-dollar award. And the case raises profound questions about the way Americans elect their judges, the duty of judges to recuse themselves when the people who bankrolled their campaigns come before them and, even, the very meaning of judicial impartiality. The facts are so compelling that John Grisham used them as a basis for his bestseller "The Appeal." On opposing sides during oral arguments Tuesday will be two of the court's most prolific and persuasive practitioners, former solicitor general Theodore B. Olson and Andrew L. Frey.

But the implications go far beyond West Virginia, energizing critics of the multimillion-dollar political campaigns that are now the norm in many of the 39 states that elect judges, where no-holds-barred television advertising has replaced the staid and polite debates of the past. Among the outpouring of supporters for Caperton are a number of unlikely compatriots -- Wal-Mart siding with the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law, for instance. "It's about the fundamental responsibility of the judiciary: a fair hearing before an impartial arbiter," said James Sample of the Brennan Center. "This is a fact-bound, multi-factor, worst-of-the-worst scenario; if any sort of floor exists for due process, this is the best case to plumb those depths."

But the facts, according to Caperton's nemesis, Don Blankenship, chief executive of A.T. Massey Coal Co., are these: Blankenship made lawful contributions to and on behalf of now-Justice Brent Benjamin. As in other political causes he has supported, he has a right to his political views about who is best to serve on the West Virginia Supreme Court. And there is no evidence that Benjamin had anything to gain financially from the dispute between Caperton and Blankenship, the only reason for recusal the Supreme Court until now has recognized. Blankenship attorney Frey, in his brief to the court, rejects arguments from Caperton that Benjamin had an obligation to recuse himself because of bias or "the probability of bias" or because he owed Blankenship a "debt of gratitude." "Such a theory . . . would have no limiting principle, would be entirely unworkable and would create serious administrative problems for courts," Frey wrote.

He spins an intriguing set of conflicts. Should a judge sit on a case involving a newspaper that endorsed his campaign? Is recusal necessary when one party is an interest group that worked for the judge's election? If the justice Blankenship worked so hard to oust had been reelected, would he harbor such animus that he should recuse himself from the case? "If 'probability of bias' were the constitutional standard," Frey wrote to the justices, "many members of this court would quite likely have been acting unconstitutionally by participating in numerous cases decided over the past 200 years." Caperton attorney Olson dismisses such a "slippery-slope/parade-of-horrible argument" as a distraction. "The thing I ask people is: 'If you had an important case coming up and your opponent gave $3 million to elect the judge who was going to decide it, would you think that was fair?'" Olson said. "I haven't met a person yet who thinks that's fair."

Caperton said that certainly was his thought in 2006, the first time he entered the ornate chambers of the West Virginia Supreme Court. His legal battles had been largely successful to that point, despite what he said was an early warning from Blankenship. "He said, 'I spend a million dollars a month on attorneys, and I'll tie you up for years in court,' " Caperton said. " 'Every expert you get, I'll find three.' " Blankenship and Benjamin declined to be interviewed. Nevertheless, Caperton convinced juries in Virginia and West Virginia that Massey Coal's business tactics -- including buying Caperton's coal purchaser and canceling contracts -- had unlawfully driven Caperton out of business. Blankenship appealed to the West Virginia high court, but not before he got heavily involved in its 2004 elections. Although he gave only the allowed maximum $1,000 to Benjamin's campaign, he formed a political fundraising organization to "beat Warren McGraw," a longtime state politician and justice who was up for reelection and would be Benjamin's opponent.

The $3 million Blankenship spent on the race was more than all of Benjamin's other contributors combined. Blankenship and business groups supported Benjamin, labor unions and defense lawyers supported McGraw, and the result was one of the nastiest races in state history. "I'd been in some of the meanest campaigns in West Virginia," said McGraw, who has served in many state political offices and is now a judge in tiny Pineville. "But this campaign for the Supreme Court was without honor." Though Blankenship's dispute with Caperton was in the background of the race, the ads portrayed McGraw as voting to release a child molester: "Letting a child rapist go free? To work in our schools? That's radical Justice Warren McGraw." Benjamin, the first non-incumbent Republican elected to the court since the 1920s, declined to recuse himself when Blankenship's appeal reached the court. "No objective information is advanced to show that this justice has a bias for or against any litigant . . . or that this justice will be anything but fair and impartial," he wrote.

So when Caperton entered the court that day and looked at the five justices who would decide his case, he saw one whose campaign was financed by Blankenship and another rumored to be one of Blankenship's best friends. "I'm not thinking due process and I'm not thinking 14th Amendment; as a citizen I'm sitting there saying, 'How in the world? I've got two votes against me and we haven't even started yet,' " Caperton said. The court reversed the award, 3 to 2, saying among other things that the suit was not filed in the proper jurisdiction. But that was only the beginning of what became something of a meltdown on the West Virginia Supreme Court. Caperton's attorney received photos of Blankenship and Justice Elliott "Spike" Maynard, the one with whom he was rumored to be friendly, at a dinner on vacation on the French Riviera. And Justice Larry Starcher was quoted in the New York Times saying Blankenship's bankrolling of Benjamin's campaign made him want to "puke."

A rehearing was scheduled, with two circuit judges taking the places of Maynard and Starcher. The vote again was 3-2, with Benjamin again casting the decisive vote. "I just want a hearing in front of an impartial court of justices," Caperton said, and his petition asks for a remand to the West Virginia Supreme Court, without Benjamin. Caperton has drawn lopsided support in the case from legal and business groups, as well as those who worry about the role money now plays in judicial elections. Wal-Mart joined with Lockheed Martin, Pepsi and other corporations on Caperton's side, telling the court in a brief that requiring Benjamin's recusal "would signal to businesses and the general public that judicial decisions cannot be bought and sold."

Justice at Stake, a judicial reform group that has been sounding the alarm about the role of money in judges' races, notes that the amount of money raised by state supreme court candidates from 2000 to 2007 was almost $168 million, nearly double that raised during the 1990s. Former Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O'Connor is among those sharply critical of those elections. The Justice at Stake brief, joined by Common Cause, the League of Women Voters and a host of others, warns the court that it would "weaken state reform efforts" to find no "constitutionally significant threat to equal justice" in the case. Frey said the real goal of those lined up against his client is their desire that judges be appointed, not elected. "I'm no fan of judicial elections either, but it's not the job of the Supreme Court" to decide that, Frey said. The other side, Frey said, would erase the "presumption that a judge really will be impartial." And he said that in all the briefs filed on behalf of his opponent, no one proposes a clear line for what level of support -- be it financial or editorial or even gratitude to the chief executive who appointed a judge -- to call that presumption of impartiality into question.

4 comments:

But, not in New York. These thugs just do whatever they want.

I found as a long time court clerk in Buffalo NY, that most judges correctly used the recusal option.

Most of them rarely used it and those that did, mostly did it for absolutely appropriate causes.

We did have a few judges over the years that used it to remove cases from his/her caseload, so the difficult ones (trial worthy) would leave their count and give them more time to take off!

The most prominent one that strikes me as worthy of proposing and issuing strict guidelines relative to recusals, is the one where a female judge returned a file..because she did not believe the recusal was necessary.

Judges do not have to state what the reason for the recusal is...but this lady judge learned about it from the DA.

The reason for the recusal was... an ex-judge was appearing in front of the recusing judge and that judge's court clerk had participated in the heavily reported removal of that judge from the bench. The clerk was harassed by that judge and his wife for years and if the presiding judge was to maintain a working relationship with his clerk, as well as having any concern for her well being and not liking that judge himself for the reasons he was removed and knowing the people that were involved... as he was friends with them......he knew he must remove that ONE case. I repeat...one case!

This female judge...who is now in county court...always had an issue with this very public sexual harassment case, and really was just mad that was the reason for the judge's recusal..so she decided that that judge was not prejudiced.....because she certainly wasn't...and returned the case...complaining, screaming and making a huge issue of it throughout the courthouse...didn't you Shirley T!

This case was the only time in my 30 yrs that a judge determined what was in another judge's mind...and negated his own mental determination. She got voted into another and higher office....as discriminatory and juvenile as she is and was.

This is why recusals must be defined and also established as non-returnable....surprisingly to the supposed learned of the law and promoters of justice. The above female judge's behavior as I have described it, is within the terms of abuse of her judicial oath.

See this in today's NYT's:

Sidebar

Supreme Court Enters the YouTube Era

this same scenario of an interested party buying a judgeship is the theme behind john grisham's latest books. I think it is called: "The Appeal".

Post a Comment