The System Is the Crime

Judicial Reports by Mark Lagerkvist - October 29, 2008

mark@lagerkvist.net

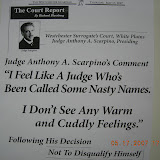

Judicial campaign committees around Albany are raising funds from law firms with business pending before the judge — and one firm is particularly generous. Supreme Court Appellate Justice Anthony J. Carpinello’s re-election campaign accepted a $10,000 gift in May from an Albany law firm that had recently appeared before him in court to argue a medical malpractice appeal. Three months after the contribution, which was disclosed in his campaign’s filings with the State Board of Elections, Carpinello cast a deciding vote in a 3-2 decision on the case, Caruso v. Northeast Emergency Medical Associates. He also wrote the majority opinion that could allow the firm, Powers & Santola, to collect as much as $200,000 in fees. The judge claims he was unaware of the contribution. “I’ve never done anything unethical in my life,” said Carpinello. “I follow the law, and I’m not supposed to know who contributes to my campaign.” The law firm, meanwhile, contends it would never give a campaign gift to a judge who could be influenced by it. “If this is somebody we think we can curry favor with by making a contribution, we won’t make the contribution,” said senior partner John K. Powers. “Because if we can curry favor, so can someone else. And that’s not somebody we want sitting on the bench.”

SERIAL SHILLING

If there is a guilty party, it is arguably the controversial process of electing judges throughout New York State. Lawyers are allowed to fork over campaign cash to judges running for re-election — even while they have cases pending before those judges. Gifts from attorneys account for roughly half of money raised by Supreme Court candidates, incumbents and challengers, for the coming election. Judges claim they are not influenced because court rules forbid them from learning who contributes to their campaigns or how much. However, details on donors are part of a public record readily available to anyone with an Internet connection.

“They’re not supposed to know who contributes money to them, but they’re also not idiots,” said Powers. “Now that it’s online, somebody’s going to mention to you, at some point, who contributed money.” For next Tuesday’s election, Justice Carpinello’s campaign has raised in excess of $238,000, more than any of the other 51 candidates running for Supreme Court seats across the State, according to its disclosures to the Board of Elections. “I am fighting for my professional career,” said Carpinello. “I’ve worked so hard to schedule my fundraisers – and I do attend because I’m permitted to be there.” A Judicial Reports investigation found that lawyers have handed out more than $116,000 to Carpinello, nearly half of the money raised by his campaign. His political committee has accepted 142 contributions from individual attorneys and 89 from law firms or partnerships, according to disclosures to State Board of Elections. Thirty-eight of the gifts from lawyers were for $1,000 or more.

THE POWERS & SANTOLA THAT BE

At the top of the list is Powers & Santola, a plaintiff’s firm that specializes in personal injury and medical malpractice cases. Its five partners and one associate frequently appear in the Supreme Court venues that surround Albany, including the Appellate Division’s Third Department, where Carpinello sits. And the firm is extraordinarily active on the campaign front, having given five-figure contributions to nine sitting Supreme Court justices, as well as Carpinello’s opponent.

Since 2004, Powers & Santola has doled out $157,725 in campaign cash to Supreme Court candidates in the firm’s primary area of practice, Judicial Reports found in an analysis of campaign filings. Those gifts included:

• $25,000 in 2004 to Presiding Appellate Justice Anthony V. Cardona of the Third Department;

• $20,125 last year to Albany County Supreme Court Justice Joseph C. Teresi;

• $15,000 in 2006 to Appellate Justice Karen K. Peters of the Third Department;

• $15,000 in 2005 to Appellate Justice Edward O. Spain of the Third Department;

• $10,000 last year to Saratoga County Supreme Court Justice Frank B. Williams (who is also Supervising Judge of the Third Judicial District); and

• $10,000 last year to Rensselaer County Supreme Court Justice George B. Ceresia, Jr. (who is also Administrative Judge of the Third District.)

That pattern continues in this year’s election. In addition to its gift to Carpinello, Powers & Santola has written five-figure checks to the following judicial campaigns:

• $10,000 to Schenectady County Supreme Court Justice Vito C. Caruso )who also serves as Administrative Judge of the Fourth District.)

• $10,000 to Saratoga County Supreme Court Justice Stephen A. Ferradino.

• $10,000 to Rensselaer County Court Judge Patrick J. McGrath, who is running against Carpinello for Supreme Court in the Nov. 4 election.

Justices Teresi, Peters, Spain, Williams, Ceresia and McGrath did not respond to calls from Judicial Reports. Through aides, Justices Cardona and Ferradino said they complied with court rules forbidding them from knowing any details about their campaign contributors in compliance. In an interview, Justice Caruso said that although he did see lawyers from Powers & Santola at two of his fundraisers this year, he does not know any details about the contributions from that firm or any other political donors.

“I really do maintain that wall between me and finding out,” said Caruso. “Anybody who wants to can go online and find out. Who’s stopping me, other than my own ethical feelings about it? People say to you, ‘Did you get my contribution?’ How the heck do I know? You look kind of foolish that you don’t know.” Caruso said he has never disqualified himself from a case because of a campaign gift, and that his court decisions could not be swayed by contributions, even if he did know who gave and how much. According to Powers, all of the solicitations from his firm were initiated by the judges’ political committees — which often regard the firm and its renowned political generosity as “low-hanging fruit” for their harvests of campaign cash. “I can’t speak for the judges, but if I were a judge, yes, I’d feel awkward about it,” said Powers. “I’d feel awkward about soliciting contributions from anyone. Because however you go about doing it, that is not going to be a perfect system from insulating you from the fact you’re trying to raise large sums of money over a short period of time.”

Also awkward may be the frequency with which Power’s firm appears in the courts of the judges it supports. Teresi, Ferradino, Ceresia, Caruso and Williams serve as trial-level Supreme Court Justices. Powers & Santola has appeared in their courts in a total of 35 cases during the past two decades, according to the New York State Unified Court System’s eCourts index. Powers & Santola has also appeared repeatedly before Judges Carpinello, Cardona, Spain and Peters in the Third Department of Supreme Court’s Appellate Division. In the past 11 years, the firm has argued 49 cases before the Third Department. In 47 of those instances, the panels of judges included at least one judge who would sooner or later accept a campaign gift of $10,000 or more from the firm. “In my view, we should have public financing of judicial elections because those are the people you want to have the most independence from even the taint of who’s giving the money,” said Powers. “But the reality is until we have that, the only people who are likely to make contributions to candidates are going to be lawyers.”

THE LATEST CONFLICT

The most recent Powers & Santola case before the Third Department was Caruso v. Northeast Emergency Medical Associates. The lead plaintiff was Thomas Caruso of Colonie, who claimed a hospital and emergency room physician failed to diagnose intracranial bleeding in 2001 that led to permanent neurological damage. The defendants were Ellis Hospital, Dr. Alex Pasquariello and Northeast, Pasquariello’s employer.

The case was settled before trial. Pasquariello agreed to pay Caruso $3 million. Ellis Hospital agreed to pay $1 million, plus assign Caruso its right to receive another $1 million, its anticipated indemnification payment from Northeast. However, Northeast refused to pay the $1 million, declaring Caruso had relinquished any rights to collect when he signed the general release in the settlement paperwork. In 2007, the trial court granted a summary judgment in Northeast’s favor. For Powers & Santola, it was a decision that could cost the firm an estimated $200,000 in lost contingency fees. The plaintiff appealed to the Supreme Court’s Appellate Division; the appeal was received by the Third Department on Oct. 15, 2007. A five-judge panel heard oral arguments on Jan. 18, 2008. Seven months later, on August 21, the case was decided by a 3-2 decision in favor of the plaintiff — and Powers & Santola.

The majority opinion, written by Carpinello, ruled that the general release was ambiguous. A dissenting opinion argued that the general release was valid. Northeast has petitioned the Appellate Division for leave to appeal to the State Court of Appeals; a decision has yet to be announced. Absent from the court record is the fact that Carpinello’s re-election campaign accepted the five-figure gift from Powers & Santola on May 13, while the case was being decided. Carpinello asserted that he has never disqualified himself from any case because of political contributions because he said he has no knowledge of those gifts. Sources confirmed that the issue of recusal was not raised in the Caruso appeal. “He probably doesn’t know it,” said Powers. “And if he does know it, he also knows I gave $10,000 to his opponent [Rensselaer County Court Judge Patrick J. McGrath]. Or maybe he knows that I gave $10,000 to his opponent but not [about] the $10,000 to him. I don’t think those things make a difference one way or another. “Is there a chance of [negative] public perception? I guess. Do those who contribute get some sort of favored treatment? If you’re talking about certain boroughs of New York City, that already exists…but it doesn’t happen up here.”

MLK said: "Injustice Anywhere is a Threat to Justice Everywhere"

End Corruption in the Courts!

Court employee, judge or citizen - Report Corruption in any Court Today !! As of June 15, 2016, we've received over 142,500 tips...KEEP THEM COMING !! Email: CorruptCourts@gmail.com

Most Read Stories

- Tembeckjian's Corrupt Judicial 'Ethics' Commission Out of Control

- As NY Judges' Pay Fiasco Grows, Judicial 'Ethics' Chief Enjoys Public-Paid Perks

- New York Judges Disgraced Again

- Wall Street Journal: When our Trusted Officials Lie

- Massive Attorney Conflict in Madoff Scam

- FBI Probes Threats on Federal Witnesses in New York Ethics Scandal

- Federal Judge: "But you destroyed the faith of the people in their government."

- Attorney Gives New Meaning to Oral Argument

- Wannabe Judge Attorney Writes About Ethical Dilemmas SHE Failed to Report

- 3 Judges Covered Crony's 9/11 Donation Fraud

- Former NY State Chief Court Clerk Sues Judges in Federal Court

- Concealing the Truth at the Attorney Ethics Committee

- NY Ethics Scandal Tied to International Espionage Scheme

- Westchester Surrogate's Court's Dastardly Deeds

Friday, October 31, 2008

Law School Dean: 2nd Circuit Chief Judge should be "ashamed of himself"

Judge's Remarks Cause Stir Over Goal of Pro Bono Work

The New York Law Journal by Mark Hamblett - October 31, 2008

Chief Judge Dennis Jacobs of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit raised some hackles earlier this month with a speech on pro bono lawyering at a Federalist Society dinner in Rochester. The Oct. 6 speech, entitled "Pro Bono for Fun and Profit," promised at the outset to be "unusually provocative" and the judge said straight away, "My point, in a nutshell, is that much of what we call legal work for the public interest is essentially self-serving: Lawyers use public interest litigation to promote their own agendas, social and political - and (on a wider plane) to promote the power and the role of the legal profession itself."

Judge Jacobs cited examples where litigation against governments and officials had unintended consequences. He criticized "so-called impact litigation" as overtly political and divorced from the requirements of standing. In one case, he said, attorneys at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law challenging the legal services statute illustrated "a mechanism that is often in the shadows, and showed how public interest litigation promotes political interests of lawyers and activists, altogether apart from any felt need by clients, who are marginalized or rendered superfluous altogether." Judge Jacobs also went out of his way to appreciate "lawyers who serve people and institutions that otherwise would be denied essential services and opportunities" and praised pro bono work for providing services in the "great tradition of American volunteerism." The speech drew some heated reaction, with Dean Erwin Chemerinsky of the University of California, Irvine School of Law, telling the National Law Journal that Judge Jacobs should be "ashamed of himself." Judge Jacobs later told a law blog that the National Law Journal article "grossly misstates what I said and think," adding later, "I support, endorse and solicit pro bono work, and my talk said just that. The talk identifies abuses."

Judge Jacobs declined to be interviewed when called on the matter, but said he was satisfied to have the full text of the speech published. Daniel L. Greenberg, former President of the Legal Aid Society and now special counsel at Schulte Roth & Zabel, where he heads the firm's pro bono program, had his own reaction to the speech. "It's ironic that a federal judge misunderstands that a pro bono lawyer prevails only after the other side has presented all of its facts, so to rail against the bringing of a lawsuit just strikes me as kind of odd," Mr. Greenberg said. Mr. Greenberg was amused by the notion of powerful pro bono attorneys overwhelming government lawyers, saying, "It just doesn't reflect the reality of what is happening." He added, "It's not incorrect to say that public interest as a category sometimes is broad in terms of the entire public's interest - by definition, there will always be somebody whose ox is gored. I've been doing this for 30 years and I've only had one case where everyone in the firm was pleased."

Here's the speech:

Speech by Judge Dennis G. Jacobs

Transcript - October 6, 2008 - Dennis G. Jacobs

The following remarks were delivered by Chief Judge Dennis Jacobs of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit befoe the Rochester Lawyers Chapter of the Federalist Society on October 6, 2008.

Pro Bono for Fun and Profit

I am deeply flattered to be speaking at the inaugural event of the Rochester chapter of the Federalist Society Lawyers Division. The reason so many people come to the Federalist Society events allover the country, is that, by tradition, the debates are lively and fairly matched and the talks are provocative and free of the usual stuff one hears at meetings of the bar associations. In honor of this occasion, I am going to make some remarks that are perhaps more than usually provocative. When lawyers gather and judges speak, you can count on hearing something on the subject of pro bono service. It is always praise of all that is done, with encouragement to do more. This evening I am going to articulate a view that you may not have heard: I will touch on some of the anti-social effects of some pro bono activity; I will try to explain why such observations are virtually never made by judges; and I will encourage the kind of pro bono activity that is an aspect of traditional American volunteerism.

My point, in a nutshell, is that much of what we call legal work for the public interest is essentially selfserving: Lawyers use public interest litigation to promote their own agendas, social and political--and (on a wider plane) to promote the power and the role of the legal profession itself. Lawyers and firms use pro bono litigation for training and experience. Big law firms use public interest litigation to assist their recruiting--to confer glamor on their work, and to give solace to overworked law associates. And it has been reported that some firms in New York City pay money to public-interest groups for the opportunity of litigating the cases that public-interest groups conceive on behalf of the clients they recruit. There are citizens in every profession, craft and walk of life who are active in promoting their own political views and agendas. When they do this, it is understood that they are advancing their own views and interests. But when lawyers do it, through litigation, it is said to be work for the public interest. . . . Well, sometimes yes, and sometimes no. When we do work of this kind, a lot of people would see it as doing well while doing bono. Prosperous law firms that prevail in pro bono litigation do not hesitate to put in for legal fees where the law allows, and happily collect compensation--often from the taxpayers--for work they have touted as their service to the public. And even if the firms donate all or part to charity, the charities are usually groups that have as their charitable object the promotion of litigation rather than (say) medical research or hurricane relief. Whether a goal is pro bono publico or anti, is often a policy and political judgment. No public good is good for everybody. Much public interest litigation, often accurately classified as impact litigation, is purely political, and transcends the interest of the named plaintiffs, who are not clients in any ordinary sense. Pro bono activity covers a host of things, but I'm going to limit myself to two major categories, which overlap, and which seem to me to call for a close look, and re-appraisal. First, litigation against governments and officials; second, so-called impact litigation.

A lot of public interest litigation is brought against governments, and against the elected and appointed officials of government. I do not delude myself that governments function all the time (or even very often) for the public benefit; and there is no doubt that people who are elected and appointed to government posts are imperfect, make mistakes, and promote themselves, their parties, or the interest groups that support them. But we should sometimes consider that in pro bono litigation, the government itself often has a fair claim to representing the public interest-and often a better claim. Everyone in government is accountable to the public (to the extent the public exacts accountability), either because they are directly elected by the people, or are appointed by elected officials, or hold their positions by virtue of civil service rules that have been created and administered over time by elected and appointed officials.

It is therefore odd that judges, juries and even the public often form the impression that the legal coalitions that sue governments and government officials are the ones who are appearing on behalf of the public interest. Representation of the public interest is high moral ground, the best location in town; so everyone struggles to occupy that space. The field is crowded: the activists and public interest lawyers, the professors and law school clinics, and the pro bono cadres in the law firms. They're in competition with government lawyers, and they often overwhelm government counsel with superior resources. But their standing to speak for the public is self-conferred, nothing more than a pretension. As a group, they (of course) do both good and harm. But, unlike public officials, they never have to take responsibility for the outcomes--intended and unintended--of the policy choices they work to impose in the courts.

I have an apt example. In the 1980s, six environmental organizations brought suit objecting to the Sicily Island Area Levee Project, a federal project to abate backwater flooding in Catahoula Parish, LA. The pro bono activists claimed, among other things, that levee construction could not proceed without an additional environmental impact statement. The District Court dismissed the complaint; but the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated and remanded on the impact claim, holding that the Army Corps of Engineers was required, in light of an intervening judicial decision, to go back and reconsider assumptions underlying its environmental impact statement, and if necessary issue another one. Circuit Judge Alvin Rubin dissented on the ground that plaintiffs failed to carry their burden of proof as to necessity of a supplemental statement. Judge Rubin pointed out that the project had been planned in 1975, that after several environmental evaluations, litigation began in 1983, and that the Court's 1985 remand would result in more lost time, further litigation attacks on whatever the Army Corps of Engineers come up with, and the possible frustration of the project. As he pointed out: The effect of the course my brethren follow is likely, if pursued in other cases, to be disastrous. [N]o project could ever be completed if the opposition is determined. I've Googled the Sicily Island Area Levee Project. The environmental groups succeeded. As late as 2002, the Army Corps of Engineers was still seeking funds to complete the project. Sicily Island was one of the areas hardest hit by Hurricane Katrina. You can look it up: Louisiana Wildlife Federation, Inc. v. York, 761 F.2d 1044 (5th Cir. 1985)

I have attended so many luncheons, banquets and cocktail parties honoring public interest lawyers. Many of the public interest groups and pro bono departments honor each other, sometimes over and over. It is very rare for anyone to question the usefulness of public interest lawyering. I was present one day many years ago at a law banquet at which then-Mayor Koch did just that. Unfortunately, the object of the retaliation was my law firm--and we were there in force because we had a table. Mayor Koch said that pro bono lawyers in the law firms frequently act to vindicate interests that are anti-social. He began to describe the case of a woman who (as I recall) had several dozen birds in her City-owned rental apartment. The City sought to evict her on the ground that she was impairing the premises and creating a health menace involving some kind of bird-caused disease that I cannot spell or pronounce. Anyway, the City was doing alright until a lawyer at myoId firm became involved--pro bono--and several years of litigation ensued in which the resources of a Wall Street litigation department were brought to bear. As the Mayor started talking about crazy pro bono litigations that were bedeviling the City, my colleague leaned over and said to me: "My God; he's going to talk about the bird lady." Mayor Koch described the issues in the litigation and its very long and expensive course, in a way that seemed to be quite amusing, at least to people at the other tables. I thought what Mayor Koch was doing was asserting the authority of his elected office as against pro bono lawyers who have neither a general responsibility for public health, nor an interest generally in the conditions or amenities enjoyed by residents of public housing.

The lady with the birds was entitled to a defense of her interests, as I recognized then and today. But, it 1S an entirely separate question whether in rendering that service, pro bono lawyers may be said to represent the public interest in any real sense. When public interest lawyers sue governments and officialdom, they have some natural advantages. What a government does in its operations is often limited by what it can spend, by the civil service employees who carry out its mandates, and by legitimate political considerations. Consequently, it is often the case that in litigation concerning government services, the government is arguing for a program that is not as effective as it would be if there were limitless resources, or on behalf of an agency that could (hypothetically) be improved--such as if every police officer had a degree in Constitutional law. Public interest lawyers, on the other hand, are often arguing for something that is better--which often means more expensive-than what the government is providing (or even can provide) . So a judge may well wonder: Why rule for the town or the state in order to achieve a less than optimal result for the people who live there?

Also, I think judges tend to assume that a government would itself wish to be ordered to spend more money and provide more services--particularly if the money comes from somewhere else. And sometimes a government administration may be politically well-disposed to the objective of the public interest counsel, and may be willing to succumb and be ordered to do what it would wish to do anyway. To my observation, government lawyers rarely argue that they are representing the right of the people to make decisions through their elected representatives: about governance, about the balancing of significant values and interests, and about priorities in the spending of public money and the deploYment of public resources. In any particular case, the government may be right or it may be wrong; but it is odd that government lawyers so easily yield the distinction and prestige of representing the public.

Now, let me turn to what is called impact litigation. Some years ago I was on a panel of my Court on a case that went to the Supreme Court, called Valasguez v. Legal Services. The record in that case offered an extraordinary look into the mechanism of public interest litigation. In a nutshell, Valasguez was a challenge to part of a federal statute governing the Legal Services Corporation, which operates by giving out grants to legal clinics and pro bono groups. The statute said that the grantees could serve individual clients seeking benefits under statutes as written, but could not bring class actions, or challenge the constitutionality of statutes. The kicker was that the statute also provided that any grantee that challenged that proviso would get no grants; this presented a problem for the lawyers in finding a plaintiff--and they set to work on the plaintiff problem.

The attorneys challenging the legal services statute were at the Brennan Center in my old law school, NYU. In order to assure that someone might have standing to challenge this statute, a scatter-shot approach was used; there were a score of plaintiffs, each one citing by affidavit the role he or she played in the prosecution of public interest litigation and therefore the interest that each had in overturning the statutory restraint on the ability of grantees to bring class actions and conduct impact litigation. The affidavits submitted to establish standing shed a bright light on a mechanism that is often in shadows, and showed how public interest litigation promotes political interests of lawyers and activists, often altogether apart from any felt need by clients, who are marginalized or rendered superfluous altogether. The plaintiffs' affidavits show that the use of LSC funds for client service to individual needy persons with legal problems is at best a secondary interest to them (a bore) as they work with indefatigable hands to channel public money toward political ends.

What do the affidavits say?

A New York City Councilmember was deprived of a body of lawyers who would "influenc[e] legislation, including engaging in lobbying activities and testifying before legislative bodies. [He] can no longer call upon various attorneys to assist" him in drafting legislation, (JA 218) or rely on them "to enforce the legislation" that he and they drafted together. (JA 217).

A plaintiff with a farmworkers group relied on a grantee to conduct "educational workshops. . to inform [farmworkersl of their rights," to represent them in "judicial, administrative and/or legislative proceedings," and to give "legal advice and training ln connection with advocacy programs." (JA 262-65). A plaintiff employed by a grantee said that she has as "an integral component of her work" to educate disabled and elderly persons about their legal rights, and then represent them in vindicating those rights. (JA 283). The managing attorney of another grantee averred she has "no interest in practicing law except on behalf of poor people, persons with disabilities, or other groups of oppressed people." (JA 186-87).

The director of special litigation at another grantee had as part of her work identifying issues and undertaking class actions "in the program's highest priority areas," "and to reach out and maintain communication with client groups to determine problems where intensified advocacy is needed." (JA 134-35). The general counsel to a grantee averred that his group has for decades worked with legal services offices, serving as a client for briefs amicus curiae, as a donor of policy analysis in class action litigation, and as a provider of expert testimony. (JA 194-95).

Another plaintiff averred that he had "donated money" to a legal services program for the elderly, with the hope that it could be spent "without any restrictions on the type of legal action taken or clients represented." The donor was, incidentally, of counsel to that organization in at least one other litigation. One of those witnesses explained that "[a] n essential part" of her work has been "public testimony and comments, bill and regulation drafting, and advocacy in legislative and regulatory forums and conducting community legal education." (JA 149). (JA 150-51).

The affidavits of the plaintiffs in the Valasguez case thereby described a reciprocating motor of political activism that ties together policy research and lobbying, litigation and briefs amicus, and the arousing of politically-targeted demographics in which lawyers go shopping for useful clients. In a couple of ways, this resembles how industries in the private sector lobby and litigate, and there is nothing unethical about these initiatives. At the same time, private-sector lobbyists don't finance their efforts with public money, do not claim or get the prestige of doing their work in the public interest--and they have honest-to-goodness clients. Lots of people work hard on political initiatives and campaigns, on every side. But they are not acting pro bono (and do not deserve that pretension): Neither are lawyers who are promoting their political agendas in the courts.

When I started talking I said that I would be articulating some views that you don't hear from judges, and I said that I would explain why this occasion--on which a judge says a single word critical of public interest litigation--is so rare. The fact is, most judges are very grateful for public interest and impact litigation. Cases in which the lawyers can and do make an impact are (by the same token) cases in which the judges can make an impact; and impacts are exercises of influence and power. Judges have little impetus to question or complain when activist lawyers identify a high-visibility issue, search out a client that has at least a nominal interest, and present for adjudication questions of consequence that expand judicial power and influence over hotly debated issues. If the question is sufficiently important, influential and conspicuous, it matters little to many judges whether the plaintiff has any palpable injury sufficient to support standing or even whether there is a client at all behind the litigation, as opposed to lawyers with a cause whose preparation for suit involves (in addition to research and drafting) the finding of a client--as a sort of technical requirement (like getting a person over 18 years old to serve the summons).

Similarly, you will hear no criticism of public interest litigation or impact litigation at the bar associations, and I submit that is for essentially the same reason. When matters of public importance are brought within the ambit of the court system, lawyers as well as judges are empowered. True, we have an adversary system, but the adversary system is staffed on every side by lawyers. There is a neutral judge, but judges are lawyers too; and it is hard for a judge to avoid an insidious bias in favor of assuming that all things important need to be contested by the workings of the legal profession, and decided by the judiciary. In the courtroom, advocates advocate, and judges rule, but lawyers as a profession encounter no competitors for influence and power. In the solution of political, social, moral and policy questions, everyone else is subordinated: public officials, the voters, the rate-payers, the clergy, the teachers and principals, the wardens, the military and the police. The lawyers and judges become the only active players, and everything that matters--the nature of the proceedings, how the issues are presented, what arguments and facts may be considered, the allowable patterns of analysis--are all decided and implemented by legal professionals and the legal profession, and dominated and ordered by what we think of proudly as the legal mind. Great harm can be done when the legal profession uses pro bono litigation to promote political ends and to advance the interests and powers of the legal profession and the judicial branch of our governments. Constitutionally necessary principles are eroded: the requirement of a case or controversy; the requirement of standing. Democracy itself is impaired: The people are distanced from their government; the priorities people vote for are re-ordered; the fisc is opened. These things are done by judges who are unelected (or designated in arcane ways), at the behest of a tiny group of ferociously active lawyers making arguments that the public (being busy about the other needs of family and work) cannot be expected to study or understand. And, on those rare occasions when our competitors protest, when elected officials and the public contend that the courts and legal profession have gone too far and have arrogated to themselves powers that belong to other branches of government, to other professions or other callings, or that would benefit from other modes of thinking (such as morals or faith), the Bar forms a cordon around the judiciary and declares that any harsh or effective criticism is an attack on judicial independence.

When I was in practice, I met my firm's benchmark hours for pro bono service, and I am as appreciative about work done for the public good as anybody else. The Second Circuit often reaches out to prevail on lawyers to represent parties and points-of-view that lack other representation, and we are grateful for such services rendered. To the extent that lawyers act as volunteers for the relief of those who require but cannot afford legal services, lawyers' work is beyond praise. I am grateful (and I think the public should be grateful) to lawyers who serve people and institutions that otherwise would be denied essential services and opportunities. I think of wills for the sick, corporate work for non-profit schools and hospitals, and the representation of pro se litigants whose claims have likely merit. (Perhaps less is done in the way of assistance to small businesses and individuals who could use help in coping with the web of regulation they encounter.) My colleague, Judge Robert A. Katzmann, has called for lawyers to step forward to assist aliens who are working their way through our immigration system, and I subscribe entirely.

These services are in a great tradition of American volunteerism. Indeed, the overwhelming weight of important volunteer services are provided by non-lawyers outside any legal context: volunteers in hospitals, hospices and nursing homes; individuals who mobilize for disaster relief; volunteers for military service; people who take care of the old and sick and children in our own families; volunteer teachers in churches and schools and prisons; members of PTAs; poll-watchers; volunteer firemen and people who maintain forests and trails; coaches in community centers; people who serve on school boards, and other local government bodies, including block associations--not to mention philanthropists. Of course, lawyers do many of these things side by side with other citizens. When lawyers contribute their professional services, they are making a contribution on a par with what countless volunteers do in other professions, crafts, and walks of life. By the same token, we are doing no more than acting in the spirit of volunteer service that animates people in every walk of life and field of endeavor. So I encourage such work. But in the policy area, we should as a profession consider dispassionately whether some public interest litigation has become an anti-social influence, whether the promotion of social and political agendas in the courts is in any real sense a service to the public, and whether the public interest would be best served by initiatives to abate somewhat the power of judges and lawyers and the legal profession as an interest group.

The New York Law Journal by Mark Hamblett - October 31, 2008

Chief Judge Dennis Jacobs of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit raised some hackles earlier this month with a speech on pro bono lawyering at a Federalist Society dinner in Rochester. The Oct. 6 speech, entitled "Pro Bono for Fun and Profit," promised at the outset to be "unusually provocative" and the judge said straight away, "My point, in a nutshell, is that much of what we call legal work for the public interest is essentially self-serving: Lawyers use public interest litigation to promote their own agendas, social and political - and (on a wider plane) to promote the power and the role of the legal profession itself."

Judge Jacobs cited examples where litigation against governments and officials had unintended consequences. He criticized "so-called impact litigation" as overtly political and divorced from the requirements of standing. In one case, he said, attorneys at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law challenging the legal services statute illustrated "a mechanism that is often in the shadows, and showed how public interest litigation promotes political interests of lawyers and activists, altogether apart from any felt need by clients, who are marginalized or rendered superfluous altogether." Judge Jacobs also went out of his way to appreciate "lawyers who serve people and institutions that otherwise would be denied essential services and opportunities" and praised pro bono work for providing services in the "great tradition of American volunteerism." The speech drew some heated reaction, with Dean Erwin Chemerinsky of the University of California, Irvine School of Law, telling the National Law Journal that Judge Jacobs should be "ashamed of himself." Judge Jacobs later told a law blog that the National Law Journal article "grossly misstates what I said and think," adding later, "I support, endorse and solicit pro bono work, and my talk said just that. The talk identifies abuses."

Judge Jacobs declined to be interviewed when called on the matter, but said he was satisfied to have the full text of the speech published. Daniel L. Greenberg, former President of the Legal Aid Society and now special counsel at Schulte Roth & Zabel, where he heads the firm's pro bono program, had his own reaction to the speech. "It's ironic that a federal judge misunderstands that a pro bono lawyer prevails only after the other side has presented all of its facts, so to rail against the bringing of a lawsuit just strikes me as kind of odd," Mr. Greenberg said. Mr. Greenberg was amused by the notion of powerful pro bono attorneys overwhelming government lawyers, saying, "It just doesn't reflect the reality of what is happening." He added, "It's not incorrect to say that public interest as a category sometimes is broad in terms of the entire public's interest - by definition, there will always be somebody whose ox is gored. I've been doing this for 30 years and I've only had one case where everyone in the firm was pleased."

Here's the speech:

Speech by Judge Dennis G. Jacobs

Transcript - October 6, 2008 - Dennis G. Jacobs

The following remarks were delivered by Chief Judge Dennis Jacobs of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit befoe the Rochester Lawyers Chapter of the Federalist Society on October 6, 2008.

Pro Bono for Fun and Profit

I am deeply flattered to be speaking at the inaugural event of the Rochester chapter of the Federalist Society Lawyers Division. The reason so many people come to the Federalist Society events allover the country, is that, by tradition, the debates are lively and fairly matched and the talks are provocative and free of the usual stuff one hears at meetings of the bar associations. In honor of this occasion, I am going to make some remarks that are perhaps more than usually provocative. When lawyers gather and judges speak, you can count on hearing something on the subject of pro bono service. It is always praise of all that is done, with encouragement to do more. This evening I am going to articulate a view that you may not have heard: I will touch on some of the anti-social effects of some pro bono activity; I will try to explain why such observations are virtually never made by judges; and I will encourage the kind of pro bono activity that is an aspect of traditional American volunteerism.

My point, in a nutshell, is that much of what we call legal work for the public interest is essentially selfserving: Lawyers use public interest litigation to promote their own agendas, social and political--and (on a wider plane) to promote the power and the role of the legal profession itself. Lawyers and firms use pro bono litigation for training and experience. Big law firms use public interest litigation to assist their recruiting--to confer glamor on their work, and to give solace to overworked law associates. And it has been reported that some firms in New York City pay money to public-interest groups for the opportunity of litigating the cases that public-interest groups conceive on behalf of the clients they recruit. There are citizens in every profession, craft and walk of life who are active in promoting their own political views and agendas. When they do this, it is understood that they are advancing their own views and interests. But when lawyers do it, through litigation, it is said to be work for the public interest. . . . Well, sometimes yes, and sometimes no. When we do work of this kind, a lot of people would see it as doing well while doing bono. Prosperous law firms that prevail in pro bono litigation do not hesitate to put in for legal fees where the law allows, and happily collect compensation--often from the taxpayers--for work they have touted as their service to the public. And even if the firms donate all or part to charity, the charities are usually groups that have as their charitable object the promotion of litigation rather than (say) medical research or hurricane relief. Whether a goal is pro bono publico or anti, is often a policy and political judgment. No public good is good for everybody. Much public interest litigation, often accurately classified as impact litigation, is purely political, and transcends the interest of the named plaintiffs, who are not clients in any ordinary sense. Pro bono activity covers a host of things, but I'm going to limit myself to two major categories, which overlap, and which seem to me to call for a close look, and re-appraisal. First, litigation against governments and officials; second, so-called impact litigation.

A lot of public interest litigation is brought against governments, and against the elected and appointed officials of government. I do not delude myself that governments function all the time (or even very often) for the public benefit; and there is no doubt that people who are elected and appointed to government posts are imperfect, make mistakes, and promote themselves, their parties, or the interest groups that support them. But we should sometimes consider that in pro bono litigation, the government itself often has a fair claim to representing the public interest-and often a better claim. Everyone in government is accountable to the public (to the extent the public exacts accountability), either because they are directly elected by the people, or are appointed by elected officials, or hold their positions by virtue of civil service rules that have been created and administered over time by elected and appointed officials.

It is therefore odd that judges, juries and even the public often form the impression that the legal coalitions that sue governments and government officials are the ones who are appearing on behalf of the public interest. Representation of the public interest is high moral ground, the best location in town; so everyone struggles to occupy that space. The field is crowded: the activists and public interest lawyers, the professors and law school clinics, and the pro bono cadres in the law firms. They're in competition with government lawyers, and they often overwhelm government counsel with superior resources. But their standing to speak for the public is self-conferred, nothing more than a pretension. As a group, they (of course) do both good and harm. But, unlike public officials, they never have to take responsibility for the outcomes--intended and unintended--of the policy choices they work to impose in the courts.

I have an apt example. In the 1980s, six environmental organizations brought suit objecting to the Sicily Island Area Levee Project, a federal project to abate backwater flooding in Catahoula Parish, LA. The pro bono activists claimed, among other things, that levee construction could not proceed without an additional environmental impact statement. The District Court dismissed the complaint; but the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated and remanded on the impact claim, holding that the Army Corps of Engineers was required, in light of an intervening judicial decision, to go back and reconsider assumptions underlying its environmental impact statement, and if necessary issue another one. Circuit Judge Alvin Rubin dissented on the ground that plaintiffs failed to carry their burden of proof as to necessity of a supplemental statement. Judge Rubin pointed out that the project had been planned in 1975, that after several environmental evaluations, litigation began in 1983, and that the Court's 1985 remand would result in more lost time, further litigation attacks on whatever the Army Corps of Engineers come up with, and the possible frustration of the project. As he pointed out: The effect of the course my brethren follow is likely, if pursued in other cases, to be disastrous. [N]o project could ever be completed if the opposition is determined. I've Googled the Sicily Island Area Levee Project. The environmental groups succeeded. As late as 2002, the Army Corps of Engineers was still seeking funds to complete the project. Sicily Island was one of the areas hardest hit by Hurricane Katrina. You can look it up: Louisiana Wildlife Federation, Inc. v. York, 761 F.2d 1044 (5th Cir. 1985)

I have attended so many luncheons, banquets and cocktail parties honoring public interest lawyers. Many of the public interest groups and pro bono departments honor each other, sometimes over and over. It is very rare for anyone to question the usefulness of public interest lawyering. I was present one day many years ago at a law banquet at which then-Mayor Koch did just that. Unfortunately, the object of the retaliation was my law firm--and we were there in force because we had a table. Mayor Koch said that pro bono lawyers in the law firms frequently act to vindicate interests that are anti-social. He began to describe the case of a woman who (as I recall) had several dozen birds in her City-owned rental apartment. The City sought to evict her on the ground that she was impairing the premises and creating a health menace involving some kind of bird-caused disease that I cannot spell or pronounce. Anyway, the City was doing alright until a lawyer at myoId firm became involved--pro bono--and several years of litigation ensued in which the resources of a Wall Street litigation department were brought to bear. As the Mayor started talking about crazy pro bono litigations that were bedeviling the City, my colleague leaned over and said to me: "My God; he's going to talk about the bird lady." Mayor Koch described the issues in the litigation and its very long and expensive course, in a way that seemed to be quite amusing, at least to people at the other tables. I thought what Mayor Koch was doing was asserting the authority of his elected office as against pro bono lawyers who have neither a general responsibility for public health, nor an interest generally in the conditions or amenities enjoyed by residents of public housing.

The lady with the birds was entitled to a defense of her interests, as I recognized then and today. But, it 1S an entirely separate question whether in rendering that service, pro bono lawyers may be said to represent the public interest in any real sense. When public interest lawyers sue governments and officialdom, they have some natural advantages. What a government does in its operations is often limited by what it can spend, by the civil service employees who carry out its mandates, and by legitimate political considerations. Consequently, it is often the case that in litigation concerning government services, the government is arguing for a program that is not as effective as it would be if there were limitless resources, or on behalf of an agency that could (hypothetically) be improved--such as if every police officer had a degree in Constitutional law. Public interest lawyers, on the other hand, are often arguing for something that is better--which often means more expensive-than what the government is providing (or even can provide) . So a judge may well wonder: Why rule for the town or the state in order to achieve a less than optimal result for the people who live there?

Also, I think judges tend to assume that a government would itself wish to be ordered to spend more money and provide more services--particularly if the money comes from somewhere else. And sometimes a government administration may be politically well-disposed to the objective of the public interest counsel, and may be willing to succumb and be ordered to do what it would wish to do anyway. To my observation, government lawyers rarely argue that they are representing the right of the people to make decisions through their elected representatives: about governance, about the balancing of significant values and interests, and about priorities in the spending of public money and the deploYment of public resources. In any particular case, the government may be right or it may be wrong; but it is odd that government lawyers so easily yield the distinction and prestige of representing the public.

Now, let me turn to what is called impact litigation. Some years ago I was on a panel of my Court on a case that went to the Supreme Court, called Valasguez v. Legal Services. The record in that case offered an extraordinary look into the mechanism of public interest litigation. In a nutshell, Valasguez was a challenge to part of a federal statute governing the Legal Services Corporation, which operates by giving out grants to legal clinics and pro bono groups. The statute said that the grantees could serve individual clients seeking benefits under statutes as written, but could not bring class actions, or challenge the constitutionality of statutes. The kicker was that the statute also provided that any grantee that challenged that proviso would get no grants; this presented a problem for the lawyers in finding a plaintiff--and they set to work on the plaintiff problem.

The attorneys challenging the legal services statute were at the Brennan Center in my old law school, NYU. In order to assure that someone might have standing to challenge this statute, a scatter-shot approach was used; there were a score of plaintiffs, each one citing by affidavit the role he or she played in the prosecution of public interest litigation and therefore the interest that each had in overturning the statutory restraint on the ability of grantees to bring class actions and conduct impact litigation. The affidavits submitted to establish standing shed a bright light on a mechanism that is often in shadows, and showed how public interest litigation promotes political interests of lawyers and activists, often altogether apart from any felt need by clients, who are marginalized or rendered superfluous altogether. The plaintiffs' affidavits show that the use of LSC funds for client service to individual needy persons with legal problems is at best a secondary interest to them (a bore) as they work with indefatigable hands to channel public money toward political ends.

What do the affidavits say?

A New York City Councilmember was deprived of a body of lawyers who would "influenc[e] legislation, including engaging in lobbying activities and testifying before legislative bodies. [He] can no longer call upon various attorneys to assist" him in drafting legislation, (JA 218) or rely on them "to enforce the legislation" that he and they drafted together. (JA 217).

A plaintiff with a farmworkers group relied on a grantee to conduct "educational workshops. . to inform [farmworkersl of their rights," to represent them in "judicial, administrative and/or legislative proceedings," and to give "legal advice and training ln connection with advocacy programs." (JA 262-65). A plaintiff employed by a grantee said that she has as "an integral component of her work" to educate disabled and elderly persons about their legal rights, and then represent them in vindicating those rights. (JA 283). The managing attorney of another grantee averred she has "no interest in practicing law except on behalf of poor people, persons with disabilities, or other groups of oppressed people." (JA 186-87).

The director of special litigation at another grantee had as part of her work identifying issues and undertaking class actions "in the program's highest priority areas," "and to reach out and maintain communication with client groups to determine problems where intensified advocacy is needed." (JA 134-35). The general counsel to a grantee averred that his group has for decades worked with legal services offices, serving as a client for briefs amicus curiae, as a donor of policy analysis in class action litigation, and as a provider of expert testimony. (JA 194-95).

Another plaintiff averred that he had "donated money" to a legal services program for the elderly, with the hope that it could be spent "without any restrictions on the type of legal action taken or clients represented." The donor was, incidentally, of counsel to that organization in at least one other litigation. One of those witnesses explained that "[a] n essential part" of her work has been "public testimony and comments, bill and regulation drafting, and advocacy in legislative and regulatory forums and conducting community legal education." (JA 149). (JA 150-51).

The affidavits of the plaintiffs in the Valasguez case thereby described a reciprocating motor of political activism that ties together policy research and lobbying, litigation and briefs amicus, and the arousing of politically-targeted demographics in which lawyers go shopping for useful clients. In a couple of ways, this resembles how industries in the private sector lobby and litigate, and there is nothing unethical about these initiatives. At the same time, private-sector lobbyists don't finance their efforts with public money, do not claim or get the prestige of doing their work in the public interest--and they have honest-to-goodness clients. Lots of people work hard on political initiatives and campaigns, on every side. But they are not acting pro bono (and do not deserve that pretension): Neither are lawyers who are promoting their political agendas in the courts.

When I started talking I said that I would be articulating some views that you don't hear from judges, and I said that I would explain why this occasion--on which a judge says a single word critical of public interest litigation--is so rare. The fact is, most judges are very grateful for public interest and impact litigation. Cases in which the lawyers can and do make an impact are (by the same token) cases in which the judges can make an impact; and impacts are exercises of influence and power. Judges have little impetus to question or complain when activist lawyers identify a high-visibility issue, search out a client that has at least a nominal interest, and present for adjudication questions of consequence that expand judicial power and influence over hotly debated issues. If the question is sufficiently important, influential and conspicuous, it matters little to many judges whether the plaintiff has any palpable injury sufficient to support standing or even whether there is a client at all behind the litigation, as opposed to lawyers with a cause whose preparation for suit involves (in addition to research and drafting) the finding of a client--as a sort of technical requirement (like getting a person over 18 years old to serve the summons).

Similarly, you will hear no criticism of public interest litigation or impact litigation at the bar associations, and I submit that is for essentially the same reason. When matters of public importance are brought within the ambit of the court system, lawyers as well as judges are empowered. True, we have an adversary system, but the adversary system is staffed on every side by lawyers. There is a neutral judge, but judges are lawyers too; and it is hard for a judge to avoid an insidious bias in favor of assuming that all things important need to be contested by the workings of the legal profession, and decided by the judiciary. In the courtroom, advocates advocate, and judges rule, but lawyers as a profession encounter no competitors for influence and power. In the solution of political, social, moral and policy questions, everyone else is subordinated: public officials, the voters, the rate-payers, the clergy, the teachers and principals, the wardens, the military and the police. The lawyers and judges become the only active players, and everything that matters--the nature of the proceedings, how the issues are presented, what arguments and facts may be considered, the allowable patterns of analysis--are all decided and implemented by legal professionals and the legal profession, and dominated and ordered by what we think of proudly as the legal mind. Great harm can be done when the legal profession uses pro bono litigation to promote political ends and to advance the interests and powers of the legal profession and the judicial branch of our governments. Constitutionally necessary principles are eroded: the requirement of a case or controversy; the requirement of standing. Democracy itself is impaired: The people are distanced from their government; the priorities people vote for are re-ordered; the fisc is opened. These things are done by judges who are unelected (or designated in arcane ways), at the behest of a tiny group of ferociously active lawyers making arguments that the public (being busy about the other needs of family and work) cannot be expected to study or understand. And, on those rare occasions when our competitors protest, when elected officials and the public contend that the courts and legal profession have gone too far and have arrogated to themselves powers that belong to other branches of government, to other professions or other callings, or that would benefit from other modes of thinking (such as morals or faith), the Bar forms a cordon around the judiciary and declares that any harsh or effective criticism is an attack on judicial independence.

When I was in practice, I met my firm's benchmark hours for pro bono service, and I am as appreciative about work done for the public good as anybody else. The Second Circuit often reaches out to prevail on lawyers to represent parties and points-of-view that lack other representation, and we are grateful for such services rendered. To the extent that lawyers act as volunteers for the relief of those who require but cannot afford legal services, lawyers' work is beyond praise. I am grateful (and I think the public should be grateful) to lawyers who serve people and institutions that otherwise would be denied essential services and opportunities. I think of wills for the sick, corporate work for non-profit schools and hospitals, and the representation of pro se litigants whose claims have likely merit. (Perhaps less is done in the way of assistance to small businesses and individuals who could use help in coping with the web of regulation they encounter.) My colleague, Judge Robert A. Katzmann, has called for lawyers to step forward to assist aliens who are working their way through our immigration system, and I subscribe entirely.

These services are in a great tradition of American volunteerism. Indeed, the overwhelming weight of important volunteer services are provided by non-lawyers outside any legal context: volunteers in hospitals, hospices and nursing homes; individuals who mobilize for disaster relief; volunteers for military service; people who take care of the old and sick and children in our own families; volunteer teachers in churches and schools and prisons; members of PTAs; poll-watchers; volunteer firemen and people who maintain forests and trails; coaches in community centers; people who serve on school boards, and other local government bodies, including block associations--not to mention philanthropists. Of course, lawyers do many of these things side by side with other citizens. When lawyers contribute their professional services, they are making a contribution on a par with what countless volunteers do in other professions, crafts, and walks of life. By the same token, we are doing no more than acting in the spirit of volunteer service that animates people in every walk of life and field of endeavor. So I encourage such work. But in the policy area, we should as a profession consider dispassionately whether some public interest litigation has become an anti-social influence, whether the promotion of social and political agendas in the courts is in any real sense a service to the public, and whether the public interest would be best served by initiatives to abate somewhat the power of judges and lawyers and the legal profession as an interest group.

Thursday, October 30, 2008

Presidential Candidates Challenged on Corruption Fix (CLICK HERE)

Presidential Candidates asked to pledge to close the IRS, and realign resources from the Treasury Department to the understaffed Justice Department to fight Public Corruption.

Integrity in the Courts

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Court Group Challenges Presidential Candidates to Close the IRS, and realign Resources from the Treasury Department to the Justice Department to fight Corruption

___________________________

Integrity in the Courts Asks All Federal Candidates To Protect Individual Liberties by Abolishing the Tax Code and IRS

Integrity in the Courts, a New York based public interest group, has joined with several other organizations to found a non-partisan Coalition to Abolish the Tax Code and the IRS. The purpose of the new coalition is to support various proposals put forth by such groups as the National Federation of Independent Businesses (seeking wide scale tax reform), Freedom Works (favoring flat tax), Americans for Fair Taxation, Fair Tax Blog, and the CATO Institute (favoring national sales tax).

These policy groups and others have as a common goal eliminating the current tax code and the Internal Revenue Service. They seek to replace the code with an entirely new tax system that would be uncomplicated, just and fair. Also, any substitute system would use as its cornerstone a consumer friendly monitoring agency, in place of one that strikes fear in the hearts of most Americans.

Under the plan, the nationwide IRS structure, and most of the 90,000-plus well-trained personnel, would be reassigned from duties under the Treasury Department to functions within the understaffed Department of Justice to specifically address issues of public corruption.

Every Citizen’s Plea is Clear: “Restore our faith in our government!”

The Coalition to Abolish the IRS is seeking to impact the presidential elections, as well as all races for Federal office. It is asking Democratic, Republican and third party candidates to sign

a pledge to vote to abolish the tax court and the IRS in the event they are elected to office.

The Coalition has issued the following statement in support of its pledge drive: “The Coalition believes that it is imperative that this tax reform effort become an essential element in the 2008 Federal elections. Without question, the outright abolishment of the current unfair, unworkable, overly complex tax system is long overdue. Most importantly, as citizens are freed from government intruding in their personal lives, the abolishment of the present tax system will restore individual creativity, drive and initiative that will be major factors in reviving the economic engine of the United States.

The Pledge

The Coalition to Abolish the IRS has requested all candidates for Federal office to execute the following pledge. The pledge below has been drawn up for the two major party presidential candidates:

I, Barack Obama/John McCain, hereby pledge to propose as a first order of business legislation to the U.S. Congress to abolish the present Tax Code and the Internal Revenue Service during my first term in office. I further pledge to support legislation to replace the present code with a system that is simple, honest, and fair. Under the new system to be proposed, the IRS will be eliminated and replaced with a mere bookkeeping agency with strictly limited powers. I am committed to fighting public corruption and will lead the nation in the restoration of the people’s faith in their government.

In addition, I hereby call on all candidates for election to the House and Senate to pledge to vote for the legislation I will propose to abolish the tax code and IRS.

For further information contact the coalition at: abolish.irs@gmail.com

For More Information, Contact:

Frank Brady at Integrity in the Courts

www.IntegrityInTheCourts.com

206-426-3558 (tel and fax)

BLOG: www.CoalitionToAbolishTheIRS.wordpress.com

########

Integrity in the Courts

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

October 30, 2008

Senator Barack Obama

713 Hart Senate Office Building

Washington, D.C. 20510 Via facsimile 202-228-4260

Senator John McCain

241 Russell Senate Office Building

Washington, D.C. Via facsimile 202-228-2862

RE: Your Signed Pledge to Restore Our Faith in Our Government

Dear Senators Obama and McCain,

Integrity in the Courts, a New York based public interest group, has joined with several other organizations to found a non-partisan Coalition to Abolish the Tax Code and the IRS. The purpose of the new coalition is to support various proposals put forth by such groups as the National Federation of Independent Businesses, Freedom Works, Americans for Fair Taxation, Fair Tax Blog, and the CATO Institute.

Under the plan, the nationwide IRS structure, and most of the 90,000-plus well-trained personnel, would be reassigned from duties under the Treasury Department to functions within the understaffed Department of Justice to specifically address issues of public corruption.

It is respectfully requested that you review the attached, and sign the following pledge:

I, __________________________, hereby pledge to propose as a first order of business legislation to the U.S. Congress to abolish the present Tax Code and the Internal Revenue Service during my first term in office. I further pledge to support legislation to replace the present code with a system that is simple, honest, and fair. Under the new system to be proposed, the IRS will be eliminated and replaced with a mere bookkeeping agency with strictly limited powers. I also pledge my commitment to fighting public corruption and will lead the nation in the restoration of the people’s faith in their government.

In addition, I hereby call on all candidates for election to the House and Senate to pledge to vote for the legislation I will propose to abolish the tax code and IRS.

Date: _________________ __________________________________

Good Luck. To all of us!

Founded by Committee for Fair Tax, Integrity in the Courts, Government Reorganization.Com, In Support of: National Federation of Independent Business, Freedom Works

The Coalition to Abolish IRS has been founded to support the goals of a number of national organizations that seek the replacement of the present burdensome, inequitable and unfair tax code and the IRS. These organizations propose replacement systems that will assure fairness, simplicity and justice, together with the abolishment of the IRS. Among the organizations supported by the Coalition are National Federation of Independent Business.

On June 17, 1998, the House of Representatives passed the Tax Code Termination Act (H.R.3097) by a 219-209 vote. The National Federation of Independent Business endorsed the legislation. On July 28, 1998, the U.S. Senate failed to pass the legislation n a 49 – 49 vote. At the time of its passage, the Tax Code Termination Act was seen as an outstanding victory for a grass roots effort of average taxpayers, small business owners, and all persons who have experienced dread and fear on receiving a notice from the IRS. Since that time, many proposals have been put forth to abolish the present tax system, but to date, they have not been made a part of national election campaigns.

The Coalition to Abolish IRS is placing the question of this fundamental tax reform on the national agenda by seeking the endorsement of all candidates for election to the House, Senate and the Presidency. All candidates for federal office are requested to take a similar pledge.

The Coalition believes that it is imperative that this tax reform legislative proposal become a central element of plans to overcome the present economic crisis. Without question, the abolishment of the present unfair, regressive system and the IRS enforcement agency will unleash individual productivity, drive, ingenuity, dedication and initiative that will generate economic growth and prosperity.

As critics well know, the present tax system in the U.S. has far more in common with plans of Karl Marx to redistribute wealth than the fundamental goal of our founding fathers to never subject our population to the unfairness of a national income taxation system. Unfortunately, the Congress long ago abandoned this basic economic freedom charted by the founders, replacing it with a grotesque tax code, which unfairly victimizes all who cannot employ tax accountants, and subjects countless honest, hard working citizens to an IRS, which assumes the taxpayer to be guilty, directly contrary to the Constitutional guarantee of presumption of innocence.

The American Revolution was fought to end the right of the King of England to destroy his subjects through unfair tax systems. The Coalition and those national organizations it supports are solely dedicated to restore fairness to the tax system, preserving the personal rights and liberties of all citizens. And in this process, the IRS, which ranks as the government’s largest, most inefficient, costly, unfair, arbitrary and unjust administrative agency, will be totally abolished.

The Coalition, on behalf of all organizations seeking fundamental reform of the U.S, tax system, invites all candidates for federal office to execute the attached pledge to abolish the tax code and the IRS. In this way, the 2008 general elections will mark the end of the present federal tax system, and the restoration of personal economic freedom with the realignment of Resources from the Treasury Department to the Justice Department to fight Public Corruption.

For More, See: www.abolishIRS.8k.com

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release

Court Group Challenges Presidential Candidates to Close the IRS, and realign Resources from the Treasury Department to the Justice Department to fight Corruption

___________________________

Integrity in the Courts Asks All Federal Candidates To Protect Individual Liberties by Abolishing the Tax Code and IRS

Integrity in the Courts, a New York based public interest group, has joined with several other organizations to found a non-partisan Coalition to Abolish the Tax Code and the IRS. The purpose of the new coalition is to support various proposals put forth by such groups as the National Federation of Independent Businesses (seeking wide scale tax reform), Freedom Works (favoring flat tax), Americans for Fair Taxation, Fair Tax Blog, and the CATO Institute (favoring national sales tax).

These policy groups and others have as a common goal eliminating the current tax code and the Internal Revenue Service. They seek to replace the code with an entirely new tax system that would be uncomplicated, just and fair. Also, any substitute system would use as its cornerstone a consumer friendly monitoring agency, in place of one that strikes fear in the hearts of most Americans.

Under the plan, the nationwide IRS structure, and most of the 90,000-plus well-trained personnel, would be reassigned from duties under the Treasury Department to functions within the understaffed Department of Justice to specifically address issues of public corruption.

Every Citizen’s Plea is Clear: “Restore our faith in our government!”

The Coalition to Abolish the IRS is seeking to impact the presidential elections, as well as all races for Federal office. It is asking Democratic, Republican and third party candidates to sign

a pledge to vote to abolish the tax court and the IRS in the event they are elected to office.

The Coalition has issued the following statement in support of its pledge drive: “The Coalition believes that it is imperative that this tax reform effort become an essential element in the 2008 Federal elections. Without question, the outright abolishment of the current unfair, unworkable, overly complex tax system is long overdue. Most importantly, as citizens are freed from government intruding in their personal lives, the abolishment of the present tax system will restore individual creativity, drive and initiative that will be major factors in reviving the economic engine of the United States.

The Pledge

The Coalition to Abolish the IRS has requested all candidates for Federal office to execute the following pledge. The pledge below has been drawn up for the two major party presidential candidates:

I, Barack Obama/John McCain, hereby pledge to propose as a first order of business legislation to the U.S. Congress to abolish the present Tax Code and the Internal Revenue Service during my first term in office. I further pledge to support legislation to replace the present code with a system that is simple, honest, and fair. Under the new system to be proposed, the IRS will be eliminated and replaced with a mere bookkeeping agency with strictly limited powers. I am committed to fighting public corruption and will lead the nation in the restoration of the people’s faith in their government.

In addition, I hereby call on all candidates for election to the House and Senate to pledge to vote for the legislation I will propose to abolish the tax code and IRS.

For further information contact the coalition at: abolish.irs@gmail.com

For More Information, Contact:

Frank Brady at Integrity in the Courts

www.IntegrityInTheCourts.com

206-426-3558 (tel and fax)

BLOG: www.CoalitionToAbolishTheIRS.wordpress.com

########

Here's the Letter sent to the Presidential Candidates and All U.S. Senators:

Integrity in the Courts

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

October 30, 2008

Senator Barack Obama

713 Hart Senate Office Building

Washington, D.C. 20510 Via facsimile 202-228-4260

Senator John McCain

241 Russell Senate Office Building

Washington, D.C. Via facsimile 202-228-2862

RE: Your Signed Pledge to Restore Our Faith in Our Government

Dear Senators Obama and McCain,

Integrity in the Courts, a New York based public interest group, has joined with several other organizations to found a non-partisan Coalition to Abolish the Tax Code and the IRS. The purpose of the new coalition is to support various proposals put forth by such groups as the National Federation of Independent Businesses, Freedom Works, Americans for Fair Taxation, Fair Tax Blog, and the CATO Institute.

Under the plan, the nationwide IRS structure, and most of the 90,000-plus well-trained personnel, would be reassigned from duties under the Treasury Department to functions within the understaffed Department of Justice to specifically address issues of public corruption.

It is respectfully requested that you review the attached, and sign the following pledge:

I, __________________________, hereby pledge to propose as a first order of business legislation to the U.S. Congress to abolish the present Tax Code and the Internal Revenue Service during my first term in office. I further pledge to support legislation to replace the present code with a system that is simple, honest, and fair. Under the new system to be proposed, the IRS will be eliminated and replaced with a mere bookkeeping agency with strictly limited powers. I also pledge my commitment to fighting public corruption and will lead the nation in the restoration of the people’s faith in their government.

In addition, I hereby call on all candidates for election to the House and Senate to pledge to vote for the legislation I will propose to abolish the tax code and IRS.

Date: _________________ __________________________________

Good Luck. To all of us!

Very truly yours,

Frank Brady for Integrity in the Courts

www.IntegrityInTheCourts.com

abolish.irs@gmail.com