Ex-Spitzer aide Dopp suspects 'improper conduct' by 3 on Troopergate panel

The New York Daily News by KENNETH LOVETT - July 29, 2008

ALBANY - Eliot Spitzer's former spokesman wants a committee that investigates lawyer misconduct to probe three members of the ethics panel that looked into the Troopergate scandal. Darren Dopp said he sent a letter to the Third Judicial Department Committee on Professional Standards asking for the review into possible "improper conduct" during the Troopergate investigation.

Dopp was one of four former top Spitzer aides the Public Integrity Commission charged last week with violating state ethics law. He is fighting those charges. His letter asks for a formal review of Commission Chairman John Feerick, Executive Director Herbert Teitelbaum and Commissioner Andrew Celli. All three are lawyers and fall under the purview of the Committee on Professional Standards, which investigates allegations of professional misconduct against attorneys. "Those who enforce ethics laws must be above reproach," Dopp wrote to committee chief lawyer Mark Ochs. In his letter, Dopp cited reports that Albany County District Attorney David Soares has evidence about improper communications between Teitelbaum and senior Spitzer aides during its probe. Soares alerted Feerick to the evidence.

"At a minimum, Mr. Teitelbaum and Mr. Feerick failed to recognize that their actions created the appearance of impropriety," he wrote. "More troubling is the possibility that some form of tampering or obstruction may have occurred." Dopp said Celli was quoted as defending Teitelbaum even though he officially recused himself from the Troopergate investigation because he's a friend of Spitzer's. "The conduct of Mr. Feerick, Teitelbaum and Celli have a direct bearing on my ability to get a fair hearing from the commission in an ongoing case," Dopp wrote. Commission spokesman Walter Ayres had no comment on the letter, though he and Teitelbaum have strongly defended the commission's performance. The state investigations commission is looking into several different Troopergate probes, including one by the Public Integrity Commission. klovett@nydailynews.com

MLK said: "Injustice Anywhere is a Threat to Justice Everywhere"

End Corruption in the Courts!

Court employee, judge or citizen - Report Corruption in any Court Today !! As of June 15, 2016, we've received over 142,500 tips...KEEP THEM COMING !! Email: CorruptCourts@gmail.com

Most Read Stories

- Tembeckjian's Corrupt Judicial 'Ethics' Commission Out of Control

- As NY Judges' Pay Fiasco Grows, Judicial 'Ethics' Chief Enjoys Public-Paid Perks

- New York Judges Disgraced Again

- Wall Street Journal: When our Trusted Officials Lie

- Massive Attorney Conflict in Madoff Scam

- FBI Probes Threats on Federal Witnesses in New York Ethics Scandal

- Federal Judge: "But you destroyed the faith of the people in their government."

- Attorney Gives New Meaning to Oral Argument

- Wannabe Judge Attorney Writes About Ethical Dilemmas SHE Failed to Report

- 3 Judges Covered Crony's 9/11 Donation Fraud

- Former NY State Chief Court Clerk Sues Judges in Federal Court

- Concealing the Truth at the Attorney Ethics Committee

- NY Ethics Scandal Tied to International Espionage Scheme

- Westchester Surrogate's Court's Dastardly Deeds

Thursday, July 31, 2008

Connecting Statewide Dots of "Ethics" Oversight Corruption

Wednesday, July 30, 2008

NY Court Reporter Busted for Dealing Cocaine

NY Court Reporter Busted for Dealing Cocaine

The New York Law Journal by Vesselin Mitev - July 30, 2008

A year-long probe into two Long Island cocaine rings has netted a freelance court reporter, according to Suffolk County District Attorney Thomas J. Spota. Barbara Divello, who had worked as a court reporter in Suffolk courthouses, was arrested along with several others on charges they funneled drugs into clubs and neighborhoods on the East End. Ms. Divello was a "major player," Mr. Spota said yesterday at a Riverhead news conference. Ms. Divello was charged with being a distributor for an East End auto-body shop owner, Salvatore Sapienza, who allegedly supplied Ms. Divello with the drugs. There was no immediate word on how long Ms. Divello had worked as a court reporter. CLICK HERE to see RELATED STORY, "Confessions of a New York Court Reporter."

The New York Law Journal by Vesselin Mitev - July 30, 2008

A year-long probe into two Long Island cocaine rings has netted a freelance court reporter, according to Suffolk County District Attorney Thomas J. Spota. Barbara Divello, who had worked as a court reporter in Suffolk courthouses, was arrested along with several others on charges they funneled drugs into clubs and neighborhoods on the East End. Ms. Divello was a "major player," Mr. Spota said yesterday at a Riverhead news conference. Ms. Divello was charged with being a distributor for an East End auto-body shop owner, Salvatore Sapienza, who allegedly supplied Ms. Divello with the drugs. There was no immediate word on how long Ms. Divello had worked as a court reporter. CLICK HERE to see RELATED STORY, "Confessions of a New York Court Reporter."

Officer of the Court Rips Off Church Money

Lawyer a suspect in church ripoff

The New York Daily News by WILLIAM SHERMAN - July 30, 2008

A lawyer close to the Brooklyn Democratic machine is suspected of stealing $218,000 from an East Flatbush church in a mortgage foreclosure deal, the Daily News has learned. The Brooklyn district attorney's office is probing allegations that Alan Rocoff, the court-appointed referee for the foreclosure, refused to turn over the money to the Faithway Deliverance Center. "My father founded the church with his own money and couldn't make the mortgage payments. When the property was foreclosed and sold, we were supposed to get what was left over," said Robert Booker Jr., son of the founding pastor of the Pentecostal church at 2525 Snyder Ave. Pastor Robert Booker Sr., who founded the church in 1978, died in May after struggling in the courts for more than five years to collect the debt.

Five different judges have heard the case and ordered Rocoff to pay up, but he hasn't; nor has he been charged. Foreclosure referees, often appointed through connections with judges, are typically paid $1,000 for what amounts to two hours' work. It involves collecting and then depositing the cash proceeds of a sale with a court clerk for eventual disbursement. Rocoff was appointed referee by his friend Brooklyn Civil Court Judge Michael Garson, who later admitted stealing $163,000 from an aunt's bank account. Garson was tossed off the bench. He quit the bar, reimbursed his aunt's estate and pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor to avoid jail.

The church property was sold on Nov.26, 2002, in foreclosure for $301,000. There was $218,556 left after the mortgage and other debts were paid. "A check in that amount was deposited in Greenpoint Savings Bank account in Cherry Hill, N.J., but Rocoff said he didn't know where the money was, and told other stories about what happened to to it," said Rubin Ferziger, who replaced Rocoff as referee on the case. At one point, Rocoff claimed the Mafia stole his bank accounts and files. Two years ago, he voluntarily suspended himself from the bar, saying he is medically unable to practice law. Neither Rocoff, his lawyer, nor a spokesman for the Brooklyn district attorney's office would comment. Described by a former associate as a "shadowy figure out of the Truman Democratic Club," Rocoff was a confidant of jailed former Brooklyn Democratic Party boss Clarence Norman. wsherman@nydailynews.com (With Scott Shifrel)

The New York Daily News by WILLIAM SHERMAN - July 30, 2008

A lawyer close to the Brooklyn Democratic machine is suspected of stealing $218,000 from an East Flatbush church in a mortgage foreclosure deal, the Daily News has learned. The Brooklyn district attorney's office is probing allegations that Alan Rocoff, the court-appointed referee for the foreclosure, refused to turn over the money to the Faithway Deliverance Center. "My father founded the church with his own money and couldn't make the mortgage payments. When the property was foreclosed and sold, we were supposed to get what was left over," said Robert Booker Jr., son of the founding pastor of the Pentecostal church at 2525 Snyder Ave. Pastor Robert Booker Sr., who founded the church in 1978, died in May after struggling in the courts for more than five years to collect the debt.

Five different judges have heard the case and ordered Rocoff to pay up, but he hasn't; nor has he been charged. Foreclosure referees, often appointed through connections with judges, are typically paid $1,000 for what amounts to two hours' work. It involves collecting and then depositing the cash proceeds of a sale with a court clerk for eventual disbursement. Rocoff was appointed referee by his friend Brooklyn Civil Court Judge Michael Garson, who later admitted stealing $163,000 from an aunt's bank account. Garson was tossed off the bench. He quit the bar, reimbursed his aunt's estate and pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor to avoid jail.

The church property was sold on Nov.26, 2002, in foreclosure for $301,000. There was $218,556 left after the mortgage and other debts were paid. "A check in that amount was deposited in Greenpoint Savings Bank account in Cherry Hill, N.J., but Rocoff said he didn't know where the money was, and told other stories about what happened to to it," said Rubin Ferziger, who replaced Rocoff as referee on the case. At one point, Rocoff claimed the Mafia stole his bank accounts and files. Two years ago, he voluntarily suspended himself from the bar, saying he is medically unable to practice law. Neither Rocoff, his lawyer, nor a spokesman for the Brooklyn district attorney's office would comment. Described by a former associate as a "shadowy figure out of the Truman Democratic Club," Rocoff was a confidant of jailed former Brooklyn Democratic Party boss Clarence Norman. wsherman@nydailynews.com (With Scott Shifrel)

Monday, July 28, 2008

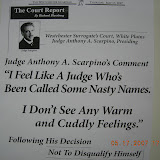

IRS Looking at Surrogate, Lawyer and Bank Chairman Link

Source Reveals the IRS is looking at the connection between Westchester County Surrogate Court Judge Anthony A. Scarpino, attorney Frank W. Streng, of White Plains-based McCarthy Fingar, and Yonkers-based Hudson Valley Bank Chairman William Griffin.

WOULD THE IRS BE INTERESTED IN WHAT’S GOING ON UNDER THE TABLES BETWEEN SCARPINO, GRIFFIN AND STRENG?

Are tax-free loans the new brown-bag payoffs that corrupt our courts?

Equity loans to judges and “gifts” to a judge’s family are not subject to annual reporting by judges, and are not income reported to the IRS. Loans for $400,000 to Surrogate Anthony Scarpino were made by Hudson Valley Bank which is controlled by William Griffin. At least $300,000 just happened to be paid to Scarpino prior to trials in which Griffin appeared before Scarpino as a witness and litigant against the Carvel family, who were represented by Frank Streng.

In 1982, the Bank and its vice president John Finnerty (who remains on the Hudson Valley Bank Business Development Board) faced and survived indictment for phony “loan” schemes and “various counts of larceny and misapplication of property”.

Why did Griffin’s bank “loan” Scarpino $400K ?

Lawyer William Griffin is the controlling shareholder and chairman of Hudson Valley Bank. Griffin also alleges to control multi-million dollar charities (including Carvel family charities “Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation”, “International Institute of Health Foods”, and others).

WOULD THE IRS BE INTERESTED IN WHAT’S GOING ON UNDER THE TABLES BETWEEN SCARPINO, GRIFFIN AND STRENG?

Are tax-free loans the new brown-bag payoffs that corrupt our courts?

Equity loans to judges and “gifts” to a judge’s family are not subject to annual reporting by judges, and are not income reported to the IRS. Loans for $400,000 to Surrogate Anthony Scarpino were made by Hudson Valley Bank which is controlled by William Griffin. At least $300,000 just happened to be paid to Scarpino prior to trials in which Griffin appeared before Scarpino as a witness and litigant against the Carvel family, who were represented by Frank Streng.

In 1982, the Bank and its vice president John Finnerty (who remains on the Hudson Valley Bank Business Development Board) faced and survived indictment for phony “loan” schemes and “various counts of larceny and misapplication of property”.

Why did Griffin’s bank “loan” Scarpino $400K ?

Lawyer William Griffin is the controlling shareholder and chairman of Hudson Valley Bank. Griffin also alleges to control multi-million dollar charities (including Carvel family charities “Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation”, “International Institute of Health Foods”, and others).

New York State Department of Banking found that Griffin’s Hudson Valley Bank altered the names on at least $5 million in U.S. Treasury securities allegedly after Thomas Carvel’s death, diverting the funds into an account co-owned and controlled by one of Griffin’s cohorts. Multi-millions that “disappeared” from all Carvel family account records at Hudson Valley Bank were one of the subjects of litigation before Scarpino. Is it any surprise that the diverted money was never returned to Agnes or Pamela Carvel?

What favors did Griffin get from undisclosed “loans”?

Neither Scarpino nor Griffin disclosed their $400,000 financial arrangements at any time. Scarpino denied a trial by jury in all Carvel cases. In the trials before Scarpino, Griffin sought to take ALL CARVEL FAMILY MONEY and end fraud investigations into the theft of over $250 million from the estates of Thomas and Agnes Carvel. Is it any surprise that Scarpino ruled in favor of Griffin against Agnes and Pamela Carvel?

Has Scarpino repeatedly paid Streng hundreds of thousands for estate litigation for throwing cases?

Streng advertised on his web site that he was an advisor to Scarpino. In other words, doesn’t Streng work for Scarpino? Neither Streng nor Scarpino disclosed their relationship at any time in the Carvel cases. Was it ever disclosed in any case? Pamela Carvel personally paid almost $1 million to Streng to fight Griffin’s involvement in charity frauds and criminal real estate scams.

Is it any surprise that Streng did nothing against Griffin? Is it any surprise that Scarpino ordered Streng to be paid almost $1 million in legal fees, but Streng refused to reimburse to Pamela Carvel the duplicate payments Streng received? Does the IRS know Streng actually received payment almost double of what he billed?

Did Scarpino repay $400K tax-free “loans” from Griffin’s bank?

The records of Westchester County Clerk and Board of Elections indicate that Westchester County Surrogate’s Court judge Anthony Scarpino received (tax-free) $400,000 from Hudson Valley Bank.

Of that sum, $100,000 was an alleged pre-election “loan” to Scarpino before his election as Surrogate. What was the security pledged for that loan? Has Scarpino ever repaid any of it?

The remaining $300,000 was alleged equity loans secured by Scarpino’s real estate in Westchester. How much of these “loans” did Scarpino repay after he ruled in Griffin’s favor?

Is the Hudson Valley Bank Development Board just another covert pay-off to loyalist politicos?

Hudson Valley Bank also runs something called “Hudson Valley Bank’s Business Development Board” of which the bank itself says, “members benefit from their association with Hudson Valley Bank” “The Board of Directors looks to fill these positions with highly-qualified professionals, who can assist in achieving the Bank’s goals.”

How much of the Bank’s record “profits” are really from diverted estate and charity assets?

James Landy is President and CEO of Hudson Valley Bank. Landy was also chairman of the board of St. Joseph’s Medial Center (and William Griffin’s wife was on that board) when Griffin bought the property next to the hospital just before a purchase grant for the very same property was given to the hospital from the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation. Not only was charity grant-money funneled to Griffin but Hudson Valley Bank also kept substantial portions of the property for itself.

Mathew Landy is James Landy’s cousin. Griffin hired Mathew Landy as the alleged office manager over one secretary for the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation – a foundation gives grants only to Griffin’s insiders since Thomas Carvel’s death.

Marc Oxman was covertly installed as guardian ad litem for Agnes Carvel without any evidence and without any hearing or trial. Oxman was hired to procure Agnes Carvel’s death by stress in London to eliminate Agnes’ claims against Griffin -- and so he did. Oxman is one of the members of the Development Board who “assists in achieving the Bank’s goals” along with Oxman’s law partner Andrew Natale, Jr.

Another Development Board member is Daniel Hollis, partner to Stuart Shamberg, attorney for Charles Lambert -- the Westchester County Public Administrator who hijacked control of Agnes Carvel’s estate into Westchester through alleged perjury by Griffin’s lawyers. Griffin’s lawyer’s alleged an “emergency” requiring the appointment of the Public Administrator for the sale 2000 acres of Carvel Dutchess County property for almost half the market value to an alleged con-man lawyer who already declared bankruptcy six months earlier -- owing Carvel businesses over $600,000. Is it any surprise that Griffin pulled off this hokey appointment at a moment when the Westchester Court lacked jurisdiction and when the law required that ALL PROCEEDINGS BE STAYED until the formal substitution of Agnes’ executor into the proceedings?

In addition to being a member of the Bank’s Development Board, Edward A. Sheeran is Executive Director of Yonkers Industrial Development Agency (“IDA”). IDA is the agency that played a part in the phony St. Joseph Hospital grant where Griffin purchased a property only after he knew his cronies in the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation approved a $2,000,000 purchase grant for a $700,000 parcel of land. Over $1,300,000 allegedly disappeared along with a corner of the property that was a branch office of Hudson Valley Bank. The IDA then stepped in to provide financing.

Michael Spicer is President and CEO of St. Joseph’s Hospital, which is the recipient of numerous unaccounted-for grants from the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation controlled by Griffin. Is it any surprise that Spicer is also “achieving the Bank’s goals” by being on the Development Board?

Lawyer Paul Amicucci is listed as being part of Griffin’s law firm. Paul Amicucci is also listed among the “Hudson Valley Bank Business Development Board” and listed as lawyer to many of the “charities” controlled by Griffin. On 6 October 2006, Griffin, allegedly acting for the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation, sold Amicucci’s brother Agnes Carvel’s $10 million former residence with 19 arcres in Ardsley, New York for only $2 million. On that same day, 6 October 2006, Amicucci’s shell company (formed in March 2006) assigned the whole property back to Griffin through Hudson Valley Bank as an alleged lease assignment for security for an alleged US$1.3 million mortgage from Hudson Valley Bank. Could this be a means for cheating Agnes’ creditors and beneficiaries who are entitled to the real income from the property?

This same Ardsley property was appraised at $1.1 million in 1990 when Thomas Carvel died. While all surrounding real estate has increased in value 300-400%, the Carvels’ unique, exclusive, mountaintop acreage property only increased about 82%. When this real estate scheme was brought before Scarpino when discovered by Pamela Carvel in 2007. Scarpino did nothing. Could this be another one of Griffin’s schemes for transferring control and profit from a property without paying taxes on the transactions? Anyone still surprised at that???

So many questions, too few answers......

What favors did Griffin get from undisclosed “loans”?

Neither Scarpino nor Griffin disclosed their $400,000 financial arrangements at any time. Scarpino denied a trial by jury in all Carvel cases. In the trials before Scarpino, Griffin sought to take ALL CARVEL FAMILY MONEY and end fraud investigations into the theft of over $250 million from the estates of Thomas and Agnes Carvel. Is it any surprise that Scarpino ruled in favor of Griffin against Agnes and Pamela Carvel?

Has Scarpino repeatedly paid Streng hundreds of thousands for estate litigation for throwing cases?

Streng advertised on his web site that he was an advisor to Scarpino. In other words, doesn’t Streng work for Scarpino? Neither Streng nor Scarpino disclosed their relationship at any time in the Carvel cases. Was it ever disclosed in any case? Pamela Carvel personally paid almost $1 million to Streng to fight Griffin’s involvement in charity frauds and criminal real estate scams.

Is it any surprise that Streng did nothing against Griffin? Is it any surprise that Scarpino ordered Streng to be paid almost $1 million in legal fees, but Streng refused to reimburse to Pamela Carvel the duplicate payments Streng received? Does the IRS know Streng actually received payment almost double of what he billed?

Did Scarpino repay $400K tax-free “loans” from Griffin’s bank?

The records of Westchester County Clerk and Board of Elections indicate that Westchester County Surrogate’s Court judge Anthony Scarpino received (tax-free) $400,000 from Hudson Valley Bank.

Of that sum, $100,000 was an alleged pre-election “loan” to Scarpino before his election as Surrogate. What was the security pledged for that loan? Has Scarpino ever repaid any of it?

The remaining $300,000 was alleged equity loans secured by Scarpino’s real estate in Westchester. How much of these “loans” did Scarpino repay after he ruled in Griffin’s favor?

Is the Hudson Valley Bank Development Board just another covert pay-off to loyalist politicos?

Hudson Valley Bank also runs something called “Hudson Valley Bank’s Business Development Board” of which the bank itself says, “members benefit from their association with Hudson Valley Bank” “The Board of Directors looks to fill these positions with highly-qualified professionals, who can assist in achieving the Bank’s goals.”

How much of the Bank’s record “profits” are really from diverted estate and charity assets?

James Landy is President and CEO of Hudson Valley Bank. Landy was also chairman of the board of St. Joseph’s Medial Center (and William Griffin’s wife was on that board) when Griffin bought the property next to the hospital just before a purchase grant for the very same property was given to the hospital from the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation. Not only was charity grant-money funneled to Griffin but Hudson Valley Bank also kept substantial portions of the property for itself.

Mathew Landy is James Landy’s cousin. Griffin hired Mathew Landy as the alleged office manager over one secretary for the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation – a foundation gives grants only to Griffin’s insiders since Thomas Carvel’s death.

Marc Oxman was covertly installed as guardian ad litem for Agnes Carvel without any evidence and without any hearing or trial. Oxman was hired to procure Agnes Carvel’s death by stress in London to eliminate Agnes’ claims against Griffin -- and so he did. Oxman is one of the members of the Development Board who “assists in achieving the Bank’s goals” along with Oxman’s law partner Andrew Natale, Jr.

Another Development Board member is Daniel Hollis, partner to Stuart Shamberg, attorney for Charles Lambert -- the Westchester County Public Administrator who hijacked control of Agnes Carvel’s estate into Westchester through alleged perjury by Griffin’s lawyers. Griffin’s lawyer’s alleged an “emergency” requiring the appointment of the Public Administrator for the sale 2000 acres of Carvel Dutchess County property for almost half the market value to an alleged con-man lawyer who already declared bankruptcy six months earlier -- owing Carvel businesses over $600,000. Is it any surprise that Griffin pulled off this hokey appointment at a moment when the Westchester Court lacked jurisdiction and when the law required that ALL PROCEEDINGS BE STAYED until the formal substitution of Agnes’ executor into the proceedings?

In addition to being a member of the Bank’s Development Board, Edward A. Sheeran is Executive Director of Yonkers Industrial Development Agency (“IDA”). IDA is the agency that played a part in the phony St. Joseph Hospital grant where Griffin purchased a property only after he knew his cronies in the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation approved a $2,000,000 purchase grant for a $700,000 parcel of land. Over $1,300,000 allegedly disappeared along with a corner of the property that was a branch office of Hudson Valley Bank. The IDA then stepped in to provide financing.

Michael Spicer is President and CEO of St. Joseph’s Hospital, which is the recipient of numerous unaccounted-for grants from the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation controlled by Griffin. Is it any surprise that Spicer is also “achieving the Bank’s goals” by being on the Development Board?

Lawyer Paul Amicucci is listed as being part of Griffin’s law firm. Paul Amicucci is also listed among the “Hudson Valley Bank Business Development Board” and listed as lawyer to many of the “charities” controlled by Griffin. On 6 October 2006, Griffin, allegedly acting for the Thomas and Agnes Carvel Foundation, sold Amicucci’s brother Agnes Carvel’s $10 million former residence with 19 arcres in Ardsley, New York for only $2 million. On that same day, 6 October 2006, Amicucci’s shell company (formed in March 2006) assigned the whole property back to Griffin through Hudson Valley Bank as an alleged lease assignment for security for an alleged US$1.3 million mortgage from Hudson Valley Bank. Could this be a means for cheating Agnes’ creditors and beneficiaries who are entitled to the real income from the property?

This same Ardsley property was appraised at $1.1 million in 1990 when Thomas Carvel died. While all surrounding real estate has increased in value 300-400%, the Carvels’ unique, exclusive, mountaintop acreage property only increased about 82%. When this real estate scheme was brought before Scarpino when discovered by Pamela Carvel in 2007. Scarpino did nothing. Could this be another one of Griffin’s schemes for transferring control and profit from a property without paying taxes on the transactions? Anyone still surprised at that???

So many questions, too few answers......

Sunday, July 27, 2008

More Smoke from Commission on Public Integrity

Teitelbaum Defends Integrity Of Spitzer Investigation

The New York Law Journal by Joel Stashenko - July 28, 2008

ALBANY - Eliot Spitzer was not charged with violating state law because, unlike four of his top subordinates, he was not involved in the misuse of State Police to discredit the ex-governor's keenest political enemy, said the executive director of the Commission on Public Integrity. Speaking Friday for the first time about the investigation that took more than 10 months to complete, Herbert Teitelbaum also defended commissioners against the "distressing" charge of being biased because of who appointed them and said investigators came to depend on advice from a "working group" of five commission members as their inquiry played out. Mr. Teitelbaum said in an interview that too much emphasis was given by the media to the manner in which purportedly damaging information on Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno was released to an Albany newspaper last summer by the Spitzer administration. That was especially true given the obscene tirade Mr. Spitzer unleashed when authorizing the release of the materials, according to testimony by his former communications secretary Darren Dopp. But Mr. Teitelbaum said the compilation of the information, not its ultimate release, was what interested the commission.

The release of the materials "may be interesting to readers of newspapers and books, but our focus was who knew what and who participated in the misuse of the State Police, or the reasonable belief of the misuse of the State Police?" Mr. Teitelbaum said. "You have to look at the record evidence. You can't make those decisions based on surmise. You can't make it on rumor . . . . How would any of us feel if we were sanctioned on the basis of rumor or surmise? It doesn't matter who you are. It doesn't matter if you are the governor or a janitor." The commission last week charged Messrs. Dopp and Preston Felton, the former acting superintendent of the State Police, with violations of Public Officers Law that could subject them to civil fines of $10,000 and $20,000 respectively. The two are challenging the charges. The commission also announced that Richard Baum, Mr. Spitzer's one-time secretary, and the governor's liaison with the State Police, William Howard, had acknowledged committing lesser violations of Public Officers Law which carry no fines. They have settled their cases. Mr. Teitelbaum reiterated Friday that the commission could renew its inquiry into Mr. Spitzer's activities if new evidence surfaces against him. In a separate interview with the Associated Press, Mr. Teitelbaum said Friday the commission might also look into whether Mr. Spitzer or someone in his office orchestrated the "obstacles" placed in the path of commission staffers as they sought information. The commission said the investigation dragged on longer than it should have because Mr. Spitzer's office resisted releasing information.

As time went on, critics openly questioned how serious the commission was about investigating Mr. Spitzer, who had appointed seven of the 13 members of the commission. The chairman, former Fordham University School of Law dean John Feerick, was picked by Mr. Spitzer to run the commission last year. Mr. Teitelbaum said Friday the commission and its staff had to take the "slings and arrows" and innuendos in silence because state Executive Law requires investigations by the agency to remain confidential until charges are brought. That stage was reached last week. "When we're attacked, when the commissioners are attacked, we can't say, 'Well, look, we're putting everybody under oath,'" Mr. Teitelbaum said. "'We're backing every request for documents with a subpoena. We're going to court to get documents. We're threatening to go to court to get documents as to which privileges were being claimed. We're taking the testimony of every high-ranking public official.'" Mr. Teitelbaum said the investigation was the most thorough one he knows of being conducted by either the Public Integrity Commission or its predecessor agencies, the Ethics and Lobbying commissions.

Unpaid Positions

He bristled at criticism that members are beholden to the officials who appointed them, or to their political parties. The unpaid commission positions are filled at the direction of the governor, legislative leaders, the state comptroller and the state attorney general. "I find it distressing, in part because the notion that a person in an unpaid position who is appointed by an elected official, the presumption that that volunteer is going to do the bidding of that elected official, I think is by and large not true, it certainly isn't true in this commission," Mr. Teitelbaum said. "It creates a misimpression in the public mind that the public believes incorrectly that people who, without compensation, who devote very, very substantial amounts of time to public service, are somehow corrupt, because that's what it would be." Mr. Teitelbaum said he has detected no partisanship in the group. "If you put bags over their heads and I put you in a room, and all you could hear is their voices, you couldn't tell who appointed whom," he said. "You wouldn't be able to tell who's a Democrat and who's a Republican. They all come to this mission with an extraordinary dedication and an extraordinary will to do the right thing." He said that with the Spitzer administration probe, he came to rely on the legal advice proffered by a "working group" of five commissioners: Mr. Feerick, former state Court of Appeals Judge Howard A. Levine and attorneys John T. Mitchell, Loretta E. Lynch and Robert J. Giuffra Jr.

Other members of the commission are Daniel R. Alonso, Virginia M. Apuzzo, John M. Brickman, Andrew G. Celli Jr., Richard D. Emery, Daniel J. French, David L. Gruenberg, and James P. King. Mr. Celli, a Spitzer friend, recused himself in this case. Mr. Teitelbaum said he did not regret leaving a secure partnership at Bryan Cave, despite the tumultuous last year for the commission and state government in Albany. He acknowledged, however, that he had never "worked in an arena where media played such a role" as with the commission's work on the Spitzer case. He joked Friday about opening the newspapers and seeing stories about a guy he can't recognize - Herbert Teitelbaum. "It's true," Mr. Teitelbaum said. "Of late, I say, 'Look at this guy. Got the same name as I do. He's also working for state government.' Wow! He's terrible." -Joel.Stashenko@incisivemedia.com

The New York Law Journal by Joel Stashenko - July 28, 2008

ALBANY - Eliot Spitzer was not charged with violating state law because, unlike four of his top subordinates, he was not involved in the misuse of State Police to discredit the ex-governor's keenest political enemy, said the executive director of the Commission on Public Integrity. Speaking Friday for the first time about the investigation that took more than 10 months to complete, Herbert Teitelbaum also defended commissioners against the "distressing" charge of being biased because of who appointed them and said investigators came to depend on advice from a "working group" of five commission members as their inquiry played out. Mr. Teitelbaum said in an interview that too much emphasis was given by the media to the manner in which purportedly damaging information on Senate Majority Leader Joseph Bruno was released to an Albany newspaper last summer by the Spitzer administration. That was especially true given the obscene tirade Mr. Spitzer unleashed when authorizing the release of the materials, according to testimony by his former communications secretary Darren Dopp. But Mr. Teitelbaum said the compilation of the information, not its ultimate release, was what interested the commission.

The release of the materials "may be interesting to readers of newspapers and books, but our focus was who knew what and who participated in the misuse of the State Police, or the reasonable belief of the misuse of the State Police?" Mr. Teitelbaum said. "You have to look at the record evidence. You can't make those decisions based on surmise. You can't make it on rumor . . . . How would any of us feel if we were sanctioned on the basis of rumor or surmise? It doesn't matter who you are. It doesn't matter if you are the governor or a janitor." The commission last week charged Messrs. Dopp and Preston Felton, the former acting superintendent of the State Police, with violations of Public Officers Law that could subject them to civil fines of $10,000 and $20,000 respectively. The two are challenging the charges. The commission also announced that Richard Baum, Mr. Spitzer's one-time secretary, and the governor's liaison with the State Police, William Howard, had acknowledged committing lesser violations of Public Officers Law which carry no fines. They have settled their cases. Mr. Teitelbaum reiterated Friday that the commission could renew its inquiry into Mr. Spitzer's activities if new evidence surfaces against him. In a separate interview with the Associated Press, Mr. Teitelbaum said Friday the commission might also look into whether Mr. Spitzer or someone in his office orchestrated the "obstacles" placed in the path of commission staffers as they sought information. The commission said the investigation dragged on longer than it should have because Mr. Spitzer's office resisted releasing information.

As time went on, critics openly questioned how serious the commission was about investigating Mr. Spitzer, who had appointed seven of the 13 members of the commission. The chairman, former Fordham University School of Law dean John Feerick, was picked by Mr. Spitzer to run the commission last year. Mr. Teitelbaum said Friday the commission and its staff had to take the "slings and arrows" and innuendos in silence because state Executive Law requires investigations by the agency to remain confidential until charges are brought. That stage was reached last week. "When we're attacked, when the commissioners are attacked, we can't say, 'Well, look, we're putting everybody under oath,'" Mr. Teitelbaum said. "'We're backing every request for documents with a subpoena. We're going to court to get documents. We're threatening to go to court to get documents as to which privileges were being claimed. We're taking the testimony of every high-ranking public official.'" Mr. Teitelbaum said the investigation was the most thorough one he knows of being conducted by either the Public Integrity Commission or its predecessor agencies, the Ethics and Lobbying commissions.

Unpaid Positions

He bristled at criticism that members are beholden to the officials who appointed them, or to their political parties. The unpaid commission positions are filled at the direction of the governor, legislative leaders, the state comptroller and the state attorney general. "I find it distressing, in part because the notion that a person in an unpaid position who is appointed by an elected official, the presumption that that volunteer is going to do the bidding of that elected official, I think is by and large not true, it certainly isn't true in this commission," Mr. Teitelbaum said. "It creates a misimpression in the public mind that the public believes incorrectly that people who, without compensation, who devote very, very substantial amounts of time to public service, are somehow corrupt, because that's what it would be." Mr. Teitelbaum said he has detected no partisanship in the group. "If you put bags over their heads and I put you in a room, and all you could hear is their voices, you couldn't tell who appointed whom," he said. "You wouldn't be able to tell who's a Democrat and who's a Republican. They all come to this mission with an extraordinary dedication and an extraordinary will to do the right thing." He said that with the Spitzer administration probe, he came to rely on the legal advice proffered by a "working group" of five commissioners: Mr. Feerick, former state Court of Appeals Judge Howard A. Levine and attorneys John T. Mitchell, Loretta E. Lynch and Robert J. Giuffra Jr.

Other members of the commission are Daniel R. Alonso, Virginia M. Apuzzo, John M. Brickman, Andrew G. Celli Jr., Richard D. Emery, Daniel J. French, David L. Gruenberg, and James P. King. Mr. Celli, a Spitzer friend, recused himself in this case. Mr. Teitelbaum said he did not regret leaving a secure partnership at Bryan Cave, despite the tumultuous last year for the commission and state government in Albany. He acknowledged, however, that he had never "worked in an arena where media played such a role" as with the commission's work on the Spitzer case. He joked Friday about opening the newspapers and seeing stories about a guy he can't recognize - Herbert Teitelbaum. "It's true," Mr. Teitelbaum said. "Of late, I say, 'Look at this guy. Got the same name as I do. He's also working for state government.' Wow! He's terrible." -Joel.Stashenko@incisivemedia.com

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Lawyer Busted for Putting Too Much Cash in Political Coffers

Lawyer Busted for Putting Too Much Cash in Political Coffers

The National Law Journal by Amanda Bronstad - July 25, 2008

Los Angeles attorney Pierce O'Donnell was indicted on federal charges of making $26,000 in "conduit" campaign contributions by reimbursing employees of his law firm who gave to a committee supporting an election campaign for mayor in 2003. O'Donnell, 61, by reimbursing others, caused 13 illegal campaign contributions to be made by 13 people to the campaign. The three-count indictment includes claims that O'Donnell made false statements to the Federal Elections Commission by failing to reveal the true nature of the contributions.

If convicted, O'Donnell faces up to 12 years in federal prison. He is expected to be arraigned next month. In 2006, as part of charges brought by the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office, O'Donnell pleaded no contest to five misdemeanor counts of using a false name while making political contributions to the 2001 mayoral campaign of James Hahn. He also agreed to pay a $155,000 fine. Separately, O'Donnell agreed to pay a $147,000 fine to the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission. That same year, the commission also issued a fine of more than $13,000 to more than half a dozen employees of O'Donnell's firm, who he allegedly reimbursed for making contributions. Pierce O'Donnell, of Los Angeles-based O'Donnell & Associates, did not return a call for comment.

The National Law Journal by Amanda Bronstad - July 25, 2008

Los Angeles attorney Pierce O'Donnell was indicted on federal charges of making $26,000 in "conduit" campaign contributions by reimbursing employees of his law firm who gave to a committee supporting an election campaign for mayor in 2003. O'Donnell, 61, by reimbursing others, caused 13 illegal campaign contributions to be made by 13 people to the campaign. The three-count indictment includes claims that O'Donnell made false statements to the Federal Elections Commission by failing to reveal the true nature of the contributions.

If convicted, O'Donnell faces up to 12 years in federal prison. He is expected to be arraigned next month. In 2006, as part of charges brought by the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office, O'Donnell pleaded no contest to five misdemeanor counts of using a false name while making political contributions to the 2001 mayoral campaign of James Hahn. He also agreed to pay a $155,000 fine. Separately, O'Donnell agreed to pay a $147,000 fine to the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission. That same year, the commission also issued a fine of more than $13,000 to more than half a dozen employees of O'Donnell's firm, who he allegedly reimbursed for making contributions. Pierce O'Donnell, of Los Angeles-based O'Donnell & Associates, did not return a call for comment.

Friday, July 25, 2008

Federal Complaint: NYS Commission on Judicial Conduct is Corrupt

Federal Complaint: New York State Commission on Judicial Conduct is Corrupt

A filing in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York says New York’s Commission on Judicial Conduct (SCJC) is a “sham” operation designed to protect certain political insiders, and to target, chill and destroy other “non-player” justices throughout the empire state.

The federal complaint alleges that the SCJC ignores its charge of upholding the ethics of New York judges, all while pursuing a small inside group’s political agenda, and is a fraud upon the citizens, judges and the state’s justice system.

Highlights of the federal filing include:

1. Plaintiff was encouraged when Appellate Division, Second Department Presiding Judge A. Gail Prudenti, directed that the allegations concerning the fraudulent assignment, internet advertising and financial sanctions be formally sent by Chief Clerk of the Court of the Appellate Division, Second Department, James Edward Pelzer to the Commission on Judicial Conduct.

2. The Commission on Judicial Conduct sent plaintiff a form letter declining to take any action.

3. Plaintiff has received numerous copies of the same denial letter sent to other complaints from the SCJC.

4. Upon information and belief, and upon a thorough review of dozens of published actions by the SCJC against certain judges, the SCJC improperly advances certain agendas against some judges, while ignoring the outrageous conduct of others.

5. Upon information and belief, the SCJC summarily ignores serious charges against select judges to advance certain agendas and to protect selected judges.

6. Upon information and belief, the SCJC is a partial arbiter of secreted agendas that provides a grossly improper disservice to plaintiff, the general public, the legal community, the system of law and, in fact, the vast majority of honorable justices of the state’s courts.

Plaintiff Discovers that the Commission on Judicial Conduct is a Sham

7. On or about Wednesday, March 5, 2008, at 10 o’clock in the morning, plaintiff met at the DDC offices with the newly appointed DDC Chief Counsel, Alan W. Friedberg who, just a few months earlier, had been the longtime Deputy Chief Counsel at the SCJC. Plaintiff had requested a meeting, and Mr. Friedberg scheduled the referenced date and time.

8. Plaintiff possesses an audio tape of the March 5, 2008 meeting with DDC Chief Counsel, and who was the prior Deputy Chief Counsel of the SCJC, Alan W. Friedberg.

9. During the meeting, Mr. Friedberg stated to plaintiff that he was a very “hands-on” type of person, and that he had, in fact been very “hands-on” at the SCJC.

10. Mr. Friedberg took great pride in stating his personal involvement in all matters and did, in fact, voice his pride in being “the person” who put Judge Garson behind bars.

11. Plaintiff did not discuss the common belief that it was Kings County District Attorney Charles J. Hynes who had prosecuted the matter of ex-judge Gerald P. Garson.

12. At no time during the March 5, 2008 meeting did Mr. Friedberg use the words “fair and impartial,” “due process” or “integrity.”

13. DDC Chief Counsel Friedberg again refused to explain to plaintiff how, why or under what authority the McQuade complaint could ever be handled by a non-existent DDC outsider, choosing instead to confront plaintiff, the complainant, personally in order to chill any pursuit of my plaintiff’s right of due process concerning an attorney’s misconduct.

14. Upon information and belief, Counsel Friedberg did concede that plaintiff was entitled to be properly represented by counsel even if, for the sake of argument, plaintiff was a mass murderer, a bank robber, the one who stole the Red Cross 9/11 monies, beat old ladies, harmed defenseless animals or was a litter bug.

15. Though he advised he was a very “hands-on” person, Mr. Friedberg told plaintiff he had never heard about the numerous submissions to the SCJC alleging that numerous judges had been involved in furthering a fraud by an attorney friend where: over $100,000.00 in Red Cross 9/11 donation money had been stolen by the justices’ friend’s client; an insurance company had been defrauded by the scheme the justices advanced; their friend’s client had committed suicide; and, the involved surrogate had confronted the pro se complainant-litigant in the courthouse lobby to voice his anger at being asked to recuse himself.

Inherent Unfairness to Judges, Attorneys and Complainants at the DDC & SCJC

16. Plaintiff’s fully documented March 5, 2008 meeting with Mr. Alan W. Friedberg provides a troubling insight by the current DDC Chief Counsel, and the former SCJC Deputy Chief Counsel, into the lack of due process at both “ethics” entities. Personal agendas and selective enforcement have completely replaced the charge of ethics oversight at the DDC and the SCJC. If, for the sake of argument, Mr. Friedberg was truthful in stating he had never heard of the various issues raised by plaintiff over the past few years, then the issue becomes who is really in charge at the DDC and SCJC.

17. Upon information and belief, lower level employees at the DDC and the SCJC, and who are improperly beholden to political and legal outsiders, advance or thwart selective ethics inquiries without regard to merit.

18. As a result of the March 5, 2008 meeting at the DDC, plaintiff corresponded with Mr. Friedberg of the DDC and with the Chief Counsel of the SCJC (Exhibit “G”). Plaintiff cannot confirm if the SCJC Chief Counsel has personally received the documents as the typical terminating form letter was the only response.

To see the filed federal complaint and exhibits, CLICK HERE

A filing in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York says New York’s Commission on Judicial Conduct (SCJC) is a “sham” operation designed to protect certain political insiders, and to target, chill and destroy other “non-player” justices throughout the empire state.

The federal complaint alleges that the SCJC ignores its charge of upholding the ethics of New York judges, all while pursuing a small inside group’s political agenda, and is a fraud upon the citizens, judges and the state’s justice system.

Highlights of the federal filing include:

1. Plaintiff was encouraged when Appellate Division, Second Department Presiding Judge A. Gail Prudenti, directed that the allegations concerning the fraudulent assignment, internet advertising and financial sanctions be formally sent by Chief Clerk of the Court of the Appellate Division, Second Department, James Edward Pelzer to the Commission on Judicial Conduct.

2. The Commission on Judicial Conduct sent plaintiff a form letter declining to take any action.

3. Plaintiff has received numerous copies of the same denial letter sent to other complaints from the SCJC.

4. Upon information and belief, and upon a thorough review of dozens of published actions by the SCJC against certain judges, the SCJC improperly advances certain agendas against some judges, while ignoring the outrageous conduct of others.

5. Upon information and belief, the SCJC summarily ignores serious charges against select judges to advance certain agendas and to protect selected judges.

6. Upon information and belief, the SCJC is a partial arbiter of secreted agendas that provides a grossly improper disservice to plaintiff, the general public, the legal community, the system of law and, in fact, the vast majority of honorable justices of the state’s courts.

Plaintiff Discovers that the Commission on Judicial Conduct is a Sham

7. On or about Wednesday, March 5, 2008, at 10 o’clock in the morning, plaintiff met at the DDC offices with the newly appointed DDC Chief Counsel, Alan W. Friedberg who, just a few months earlier, had been the longtime Deputy Chief Counsel at the SCJC. Plaintiff had requested a meeting, and Mr. Friedberg scheduled the referenced date and time.

8. Plaintiff possesses an audio tape of the March 5, 2008 meeting with DDC Chief Counsel, and who was the prior Deputy Chief Counsel of the SCJC, Alan W. Friedberg.

9. During the meeting, Mr. Friedberg stated to plaintiff that he was a very “hands-on” type of person, and that he had, in fact been very “hands-on” at the SCJC.

10. Mr. Friedberg took great pride in stating his personal involvement in all matters and did, in fact, voice his pride in being “the person” who put Judge Garson behind bars.

11. Plaintiff did not discuss the common belief that it was Kings County District Attorney Charles J. Hynes who had prosecuted the matter of ex-judge Gerald P. Garson.

12. At no time during the March 5, 2008 meeting did Mr. Friedberg use the words “fair and impartial,” “due process” or “integrity.”

13. DDC Chief Counsel Friedberg again refused to explain to plaintiff how, why or under what authority the McQuade complaint could ever be handled by a non-existent DDC outsider, choosing instead to confront plaintiff, the complainant, personally in order to chill any pursuit of my plaintiff’s right of due process concerning an attorney’s misconduct.

14. Upon information and belief, Counsel Friedberg did concede that plaintiff was entitled to be properly represented by counsel even if, for the sake of argument, plaintiff was a mass murderer, a bank robber, the one who stole the Red Cross 9/11 monies, beat old ladies, harmed defenseless animals or was a litter bug.

15. Though he advised he was a very “hands-on” person, Mr. Friedberg told plaintiff he had never heard about the numerous submissions to the SCJC alleging that numerous judges had been involved in furthering a fraud by an attorney friend where: over $100,000.00 in Red Cross 9/11 donation money had been stolen by the justices’ friend’s client; an insurance company had been defrauded by the scheme the justices advanced; their friend’s client had committed suicide; and, the involved surrogate had confronted the pro se complainant-litigant in the courthouse lobby to voice his anger at being asked to recuse himself.

Inherent Unfairness to Judges, Attorneys and Complainants at the DDC & SCJC

16. Plaintiff’s fully documented March 5, 2008 meeting with Mr. Alan W. Friedberg provides a troubling insight by the current DDC Chief Counsel, and the former SCJC Deputy Chief Counsel, into the lack of due process at both “ethics” entities. Personal agendas and selective enforcement have completely replaced the charge of ethics oversight at the DDC and the SCJC. If, for the sake of argument, Mr. Friedberg was truthful in stating he had never heard of the various issues raised by plaintiff over the past few years, then the issue becomes who is really in charge at the DDC and SCJC.

17. Upon information and belief, lower level employees at the DDC and the SCJC, and who are improperly beholden to political and legal outsiders, advance or thwart selective ethics inquiries without regard to merit.

18. As a result of the March 5, 2008 meeting at the DDC, plaintiff corresponded with Mr. Friedberg of the DDC and with the Chief Counsel of the SCJC (Exhibit “G”). Plaintiff cannot confirm if the SCJC Chief Counsel has personally received the documents as the typical terminating form letter was the only response.

To see the filed federal complaint and exhibits, CLICK HERE

Thursday, July 24, 2008

"Misprision of a felony" Charges Needed in NY to Clean-Up Court Corruption

MISPRISION OF FELONY - Whoever, having knowledge of the actual commission of a felony cognizable by a court of the U.S., conceals and does not as soon as possible make known the same to some judge or other person in civil or military authority under the U.S. 18 USC. Misprision of felony, is the like concealment of felony, without giving any degree of maintenance to the felon for if any aid be given him, the party becomes an accessory after the fact.

Famed Litigator, Son Ordered to Different Federal Prisons

By The Associated Press - New York Lawyer - July 24, 2008

Famed anti-tobacco lawyer Richard "Dickie" Scruggs has been ordered to report to a federal prison in Ashland, Ky., next month to start serving his five-year sentence for attempting to bribe a Mississippi judge. Documents filed Wednesday in federal court in Oxford, Miss., also showed Scruggs' son, Zach, will go to a federal prison in Pensacola, Fla., to serve his 14-month sentence for failing to report the crime. Sidney Backstrom, also convicted of attempted bribery and sentenced to 28 months, previously was ordered to report to the prison in Forrest City, Ark. Dickie Scruggs and Backstrom are each to report to prison by Aug. 4. Zach Scruggs was told to report by Aug. 15. In documents filed with the court Tuesday, Zach Scruggs asked that he and his father both be sent to the prison in Forrest City, Ark. Zach Scruggs said that sending them to the same prison would "ease the travel burden" on his family, especially his "health-embattled mother," Diane, who has Crohn's disease, a gastrointestinal disorder.

Dickie Scruggs was indicted in November along with his son and Backstrom after another attorney wore a wire for the FBI and secretly recorded conversations about the plan to bribe Lafayette County Circuit Judge Henry Lackey. Prosecutors said the elder Scruggs wanted a favorable ruling in a dispute over $26.5 million in legal fees from a mass settlement of Hurricane Katrina insurance cases. Dickie Scruggs and Backstrom pleaded guilty in March to conspiring to bribe Lackey with $50,000. Zach Scruggs pleaded guilty in March to misprision of a felony, meaning he knew a crime was committed but didn't report it. Dickie Scruggs gained fame in the 1990s by using a corporate insider against tobacco companies in lawsuits that resulted in a $206 billion settlement. That case was portrayed in the 1999 film "The Insider" that starred Al Pacino and Russell Crowe.

By The Associated Press - New York Lawyer - July 24, 2008

Famed anti-tobacco lawyer Richard "Dickie" Scruggs has been ordered to report to a federal prison in Ashland, Ky., next month to start serving his five-year sentence for attempting to bribe a Mississippi judge. Documents filed Wednesday in federal court in Oxford, Miss., also showed Scruggs' son, Zach, will go to a federal prison in Pensacola, Fla., to serve his 14-month sentence for failing to report the crime. Sidney Backstrom, also convicted of attempted bribery and sentenced to 28 months, previously was ordered to report to the prison in Forrest City, Ark. Dickie Scruggs and Backstrom are each to report to prison by Aug. 4. Zach Scruggs was told to report by Aug. 15. In documents filed with the court Tuesday, Zach Scruggs asked that he and his father both be sent to the prison in Forrest City, Ark. Zach Scruggs said that sending them to the same prison would "ease the travel burden" on his family, especially his "health-embattled mother," Diane, who has Crohn's disease, a gastrointestinal disorder.

Dickie Scruggs was indicted in November along with his son and Backstrom after another attorney wore a wire for the FBI and secretly recorded conversations about the plan to bribe Lafayette County Circuit Judge Henry Lackey. Prosecutors said the elder Scruggs wanted a favorable ruling in a dispute over $26.5 million in legal fees from a mass settlement of Hurricane Katrina insurance cases. Dickie Scruggs and Backstrom pleaded guilty in March to conspiring to bribe Lackey with $50,000. Zach Scruggs pleaded guilty in March to misprision of a felony, meaning he knew a crime was committed but didn't report it. Dickie Scruggs gained fame in the 1990s by using a corporate insider against tobacco companies in lawsuits that resulted in a $206 billion settlement. That case was portrayed in the 1999 film "The Insider" that starred Al Pacino and Russell Crowe.

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

Insider Says Bruno Charges Mirror FBI's Currie Corruption Case

FBI: Currie used influence for chain's benefit

The Associated Press - July 23, 2008

BALTIMORE (AP) - Influential state Sen. Ulysses Currie used his office to benefit a company he was working for, according to an affidavit written by an FBI special agent who specializes in federal public corruption cases. Currie worked as a consultant for Shoppers Food Warehouse but did not disclose income from the company on ethics forms. His dealings with the grocery chain are being investigated by the FBI. Currie, 70, declined to comment to The Associated Press on Tuesday evening. An affidavit for a search warrant unsealed Tuesday at the request of several news organizations says Currie, who chairs the Senate Budget and Taxation Committee, also had 320 phone contacts with employees of Shoppers and its parent company over the last five years. The affidavit shows that in 2005 and 2006 while the transfer of a liquor license from one store to another was being considered, phone records showed "frequent contact" between Currie's numbers and those of Shoppers representatives, Prince George's County's chief liquor inspector and a county liquor board attorney. It also shows contacts before the opening of a Shoppers store at Mondawmin Mall in Baltimore and states mall owners needed state land for a renovation key to Shoppers' decision to open a store there.

FBI special agent Steven Quisenberry, who specializes in federal public corruption cases, writes in the affidavit that the Prince George's County Democrat voted on bills that affected Shoppers during the time he received payments from the company and he believes Currie used his influence to benefit Shoppers. "During the time period that Currie received payments from SFW and SuperValu, Currie voted on a number of bills that impacted, or would have impacted, the grocery industry and therefore, SFW and its parent company SuperValu," Quisenberry wrote. "Based on the facts set forth in this affidavit, it is my belief that Currie used his official position and influence in connection with such legislation and in certain business transactions involving the State of Maryland, in ways that benefited or would have benefited SFW and SuperValu."

Information about how much Shoppers paid Currie was temporarily redacted from the affidavit at the request of Currie's attorney, Dale Kelberman. In hearings Monday, Kelberman argued that Currie has not been charged and his right to privacy outweighs the public's right to access. Kelberman has until Monday to file an appeal, effectively extending the redaction until the case reaches the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit in Richmond, Va. Currie's ties to Shoppers, where he worked as an outside consultant, are under federal investigation. His District Heights home and the chain's Lanham headquarters were searched by the FBI on May 29 as part of the investigation. The affidavit indicates Currie is being investigated in connection with mail and wire fraud schemes "regarding money and property and the deprivation of the intangible right to honest services."

The Associated Press - July 23, 2008

BALTIMORE (AP) - Influential state Sen. Ulysses Currie used his office to benefit a company he was working for, according to an affidavit written by an FBI special agent who specializes in federal public corruption cases. Currie worked as a consultant for Shoppers Food Warehouse but did not disclose income from the company on ethics forms. His dealings with the grocery chain are being investigated by the FBI. Currie, 70, declined to comment to The Associated Press on Tuesday evening. An affidavit for a search warrant unsealed Tuesday at the request of several news organizations says Currie, who chairs the Senate Budget and Taxation Committee, also had 320 phone contacts with employees of Shoppers and its parent company over the last five years. The affidavit shows that in 2005 and 2006 while the transfer of a liquor license from one store to another was being considered, phone records showed "frequent contact" between Currie's numbers and those of Shoppers representatives, Prince George's County's chief liquor inspector and a county liquor board attorney. It also shows contacts before the opening of a Shoppers store at Mondawmin Mall in Baltimore and states mall owners needed state land for a renovation key to Shoppers' decision to open a store there.

FBI special agent Steven Quisenberry, who specializes in federal public corruption cases, writes in the affidavit that the Prince George's County Democrat voted on bills that affected Shoppers during the time he received payments from the company and he believes Currie used his influence to benefit Shoppers. "During the time period that Currie received payments from SFW and SuperValu, Currie voted on a number of bills that impacted, or would have impacted, the grocery industry and therefore, SFW and its parent company SuperValu," Quisenberry wrote. "Based on the facts set forth in this affidavit, it is my belief that Currie used his official position and influence in connection with such legislation and in certain business transactions involving the State of Maryland, in ways that benefited or would have benefited SFW and SuperValu."

Information about how much Shoppers paid Currie was temporarily redacted from the affidavit at the request of Currie's attorney, Dale Kelberman. In hearings Monday, Kelberman argued that Currie has not been charged and his right to privacy outweighs the public's right to access. Kelberman has until Monday to file an appeal, effectively extending the redaction until the case reaches the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit in Richmond, Va. Currie's ties to Shoppers, where he worked as an outside consultant, are under federal investigation. His District Heights home and the chain's Lanham headquarters were searched by the FBI on May 29 as part of the investigation. The affidavit indicates Currie is being investigated in connection with mail and wire fraud schemes "regarding money and property and the deprivation of the intangible right to honest services."

Open Letter to Chief Administrative Judge Pfau on DDC Corruption

Will Galison

532 LaGuardia Place # 349

New York, New York 10012

To:

532 LaGuardia Place # 349

New York, New York 10012

To:

Hon. Ann Pfau, Chief Administrative Judge

Office of Court Administration

25 Beaver Street

New York, NY 10004 BY FAX AND BY HAND

July 19, 2008

Your Honor,

I am one of a group of ten New Yorkers who have filed federal lawsuits against the Office ofCourt Administration on grounds including obstruction of justice and official misconduct. All of our suits are substantially related to the claims of Ms. Christine Anderson, a former Investigating Attorney of the First Departmental Disciplinary Committee who was fired after reporting systemic corruption at the highest level of the DDC. I recently withdrew my federal lawsuit, because I felt that I had not yet exhausted every non-litigious recourse in resolving my grievances with the OCA.

Over the past several months, I have endeavored to communicate with Mr. Allan Friedberg and Judge John Lippman, to see if they would work with me to resolve my grievances regarding the OCA so that I might avoid re-filing my lawsuit. Sadly, my good faith efforts have been met with deceit, condescension and adamant adherence to the illegal practices oftheir predecessors, Thomas Cahill and John Buckley.

This letter to you is my final attempt to avoid re-filing my suit against the OCA. The behaviorof your subordinates at the DDC is so audacious, contemptuous and blatantly illegal that they appear to believe they have been given carte blanche to desecrate the rules and reputation of the First Department. I earnestly hope they are mistaken and that the reason they have not been held to account is that Your Honor has been unaware of the improprieties of Mr. Friedberg and his colleagues in their capacities as officers and representatives of the court for which you are responsible.

Violation and Distortion of Section 605.9

Though the list of improprieties perpetrated by Mr. Cahill and the DDC (and perpetuated by Mr. Friedberg) can be found in Ms. Anderson’s lawsuit and her related affidavits, this letter will focus on one specific practice, which is emblematic of the DDC’s disregard for the rules of the First Department and their propensity for protecting favored attorneys.

This practice is the illegal citing of “pending” or “related litigation” as an excuse to defer or close investigations of attorneys he wishes to protect. As I will demonstrate, not only does this practice directly violate of Section 605.9 of the Rules of the Unified Court System, but it leads to outrageous ramifications, including giving unethical attorneys a powerful incentive to improperly delay and prolong legal procedures.

In a letter dated 5/19/06 former Chief Counsel Cahill wrote: “Since your complaint involves parties that are in the midst of litigation, we have decided to close our investigation at this time.” The “parties” cited by Mr. Cahill were, at the time, not defendants in a civil case, but merely lawyers of counsel to parties in a civil case. Even after these lawyers withdrew as counsel in the case, Mr. Cahill’s successor, Allan Friedberg, continues to maintain that they are immune from investigation, solely because they had been of counsel to a party in the civil case at one time. Mr. Friedberg wrote: “As you know, there is pending litigation concerning the same or related facts which you allege here…Accordingly we have decided to close our investigation…The Committee…concluded that we should await the conclusion of the litigation”.

The DDC uses the words “pending” and “related” to refer to any litigation in which the accused lawyer is presently or was formerly involved as counsel. There is no provision in the Uniform Rules that allows abatement or deferment of investigations due to “pending” or“related” litigation. To the contrary, Section 605.9- the only section of the Unified Rules that deals with abatement of disciplinary investigations- is clearly intended to prohibit arbitrary, abatements of ethical investigations due to pending litigation.

605.9.1 states: “The processing of complaints involving material allegations which are substantially similar to the material allegations of pending criminal or civil litigation need not be deferred pending determination of such litigation.” 605.9.1 makes it absolutely clear that even if the ethical allegations are substantially similar to the civil or criminal case, this is not sufficient cause to close or even defer an investigation.Obviously, if the ethical allegations are not similar at all to the civil or criminal allegations,then 605.9 applies even more strictly, prohibiting the abatement of the investigation based merely on “related” litigation in another court.

Moreover, even if the subject of the ethical complaint is acquitted of substantially similar allegations in a civil or criminal case, that is STILL NOT SUFFICIENT to abate the disciplinary investigation against them. 605.9.2 states: “The acquittal of a Respondent on criminal charges or a verdict or judgment in the Respondent's favor in a civil litigation involving substantially similar material allegations shall not, in itself, justify termination of a disciplinary investigation predicated upon the same material allegations.

Acquittal of substantially similar allegations by a court of law in a case directly against accused attorneys does not exempt them from disciplinary investigation. Nevertheless, Mr.Friedman closed the investigations in my case not because the attorneys had been acquitted ofsimilar allegations in a civil case, not because the attorneys had been accused of similar allegations in a civil case, not because dissimilar allegations in the two cases arose from similar facts, not even because the attorneys are in “the midst of litigation”, but merely because the attorneys had at one time in the past been of counsel to a party in a case that isstill pending.

In my case, the civil case is still “pending” precisely due to the fact that the lawyers inquestion have broken disciplinary rules by “unnecessarily delaying and prolonging a procedure”, tampering with evidence, making false allegations, and many other egregious ethical infractions. As a result of Mr. Friedberg’s own private rule regarding abatement, these attorneys are allowed to unethically prolong the litigation precisely to avoid the ethical investigations meant to deter their unethical behavior. Mr. Friedberg’s bizarre rule is actually an incentive for delinquent lawyers to delay and prolong cases as long as possible!

The outrageous ramifications of Mr. Friedberg’s rule are illustrated in the example below:

Mr. A sues Mr. B, on the allegation that Mr. B threw a ball through Mr. A’s window.Mr. B’s lawyer then contacts Mr. A (who is represented by counsel) directly, and threatens to bring criminal charges against him if he doesn’t drop the suit against Mr. B.As a result of this unethical harassment, Mr. A files an ethical complaint with the DDC, The civil claim against Mr. B (of throwing a ball thrown through Mr. A’s window) is in no way similar to the ethical claims against Mr. B’s lawyer, which would include DR 7-104: Communicating with Represented and Unrepresented Persons and DR 7-105: Threatening Criminal Prosecution. Just because the ethical allegations against Mr. B’slawyer arose in the context of the pending broken window case, they are not “similar” or“related” to the civil allegations in any way.

Even if the ethical allegations against Mr. B’s lawyer were somehow “substantially similar” to the civil allegations against him, 605.9 deems this insufficient grounds to defer an ethical investigation. 605.9 does not even mention “related” or “pending” litigation because it would be patently outrageous for the DDC to allow Mr. B’s lawyer to continue harassing and intimidating Mr. A until the conclusion of the civil procedure -potentially for years-simply because the civil procedure is ongoing!

Under this scenario, if Mr. A files a disciplinary complaint against Mr. B’s lawyer, Mr. B’slawyer can simply cite Mr. Friedberg’s private rule, and be free to continue his abuses untilthe case is over, without so much as an admonition. If Mr. B’s lawyer can figure out ways to unnecessarily prolong and delay the litigation indefinitely, he will fare even better, because hewill be paid indefinitely, he will be allowed to intimidate Mr. A indefinitely, he will exhaust Mr. A’s finances and morale indefinitely, AND he will avoid ethical investigation indefinitely. On the other hand, what motivation does Mr. B’s lawyer have to resolve the case or cease his harassment? That is exactly why Section 605.9 was framed.

That is exactly why Mr. Friedberg and Mr.Cahill cannot be allowed to make up their own crazy rules.

De Facto Motions to Dismiss on Behalf of Accused Lawyers

Finally, the question of whether or not to commence a DDC investigation is procedurally akin to a civil court’s decision to take on a civil case. In the judicial context, if the stated claims and jurisdiction are appropriate to the court, the defendant is obliged to make a motion for dismissal, which is then considered by the court. There is nothing in the rules of the DDC that suggest a substantially different approach to vetting cases, but by citing “pending litigation”, Mr. Friedberg is making and adjudicating a de facto motion to dismiss on the attorneys’ behalf, with no input from the complainant. This is analogous to the Supreme Court undertaking and ruling on an independent investigation on behalf of the defendant to determine if a case against her is in their jurisdiction.

As it is uncontestable that my complaint refers to specific violations of specific LCPR rules by attorneys practicing law in the First Department, the jurisdiction is not in question.Therefore, the DDC’s only job is to send the complaint to the accused attorney. If that attorney has an argument as to why they should be immune from investigation (due to “pending litigation” or anything else), she or her attorney may make that argument, and the DDC must consider them in light of the (real) rules. It is not the DDC’s job to find reasonswhy the lawyers should not be investigated for complaints within their jurisdiction.

Notice, however, how Mr. Friedberg fills his letter of July 16, 2008 with paragraphs about the status of the “pending lawsuits” and discussion of certain judges dismissing claims (albeit irrelevant claims) against defendants (albeit irrelevant defendants). As I have pointed out adnauseum, even if Mr. Friedberg’s letter regarded the pertinent claims against the pertinent defendants, it would be entirely irrelevant by virtue of Section 605.9.2. What possible reason can there be for Mr. Friedberg to waste ink on irrelevant claims, defendants and decisions, other than to fool me into thinking they were relevant to the investigations of entirely distinct claims and defendants and therefore legitimate grounds for abatement?

Of the five complaints that I have filed with the DDC in the past three years, all have been against lawyers in Manhattan, all have cited specific violations of the LCPR and not one has been sent to the accused attorney. They have all been summarily closed due to “pending” or“related” litigation. Just as Mr. Cahill and Mr. Friedberg are not allowed to make up their own court rules, neither are they allowed to advocate for accused lawyers by creating and deciding sham, de facto “motions for dismissal. What they are doing is nothing less than obstruction of justice and fraud against the court.

As a taxpayer and citizen of New York City, I am demanding that the OCA investigate the illegal practices of the DDC, especially in regard to the abatement of investigations in directin violation of 605.9. It is the OCA’s obligation to investigate and rectify this outrageous situation and to punish those who have broken the law. If the OCA is too invested in this matter to fairly and effectively conduct such an investigation, it should be referred to the proper Federal authorities.

Judge Pfau; Over the past five years, I have encountered corruption, cronyism and conspiracy at every level of the Judiciary. When I received no good faith response from Mr. Cahill, Icontacted his successor, Mr. Friedberg. When I received no good faith response from Mr. Friedberg I contacted his immediate superior Judge Lippman. When I received no good faith response from Judge Lippman I contacted his immediate superior; Your Honor.

If you fail to respond in good faith, I will not bother to contact Judge Kaye. Judge Kaye is already well aware of the improprieties of the DDC. I will re-file my federal complaint naming all the parties who failed to act in response to the crystal clear butchering of Rules of the Court by high-ranking officials. By a “good faith” response, I mean a response that is honest concerned, eager to discover the facts and willing to act in earnest to rectify improprieties regardless of political considerations.

I hope and expect that you will live up to your reputation as a fair, courageous and uncorrupted Judge. If you choose to do the right thing, you will be regarded as a hero by millions of citizens and by history. I look forward to receiving your response as soon as possible.

Sincerely,

/s/

Attachments: Letters to and/ or from Allan Friedberg, Tom Cahill and Jonathan Lippman

Office of Court Administration

25 Beaver Street

New York, NY 10004 BY FAX AND BY HAND

July 19, 2008

Your Honor,