Lawyer's Phony Letter That Got Her Boss Fired Could Get Her Disbarred

The Connecticut Law Tribune by Douglas S. Malan - June 30, 2008

It started as a political story. Attorney Maureen Duggan was working for a state agency boss who, she claims, pressured her to go out for drinks with him, who worked fewer than 40 hours a week, and who played fast and loose with administrative rules in his position of power. As the sole provider for her family, Duggan told officials that she couldn't risk losing her job by challenging his actions. So she crafted an anonymous letter, filled with typos, purportedly from a parking lot attendant at the State Ethics Commission office in Hartford, and used it to kick-start a state investigation that led to the ouster of her boss, former Ethics Commission Director Alan S. Plofsky. Now, however, the focus is on Duggan and her future in the legal profession. Judicial Branch officials who investigate attorney misconduct say the reported fact pattern surrounding Duggan's case is extremely rare and most likely falls under Rules of Professional Conduct 8.4(3), which involves "dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation." Practice Book rules prohibit these officials from discussing particulars of any grievance complaint or investigation against an attorney until probable cause is found. But as for a scenario involving a deceitful letter, "it's really something that you don't see every day," said Michael P. Bowler, head counsel of the Statewide Grievance Committee. Bowler said he has seen instances of an attorney drafting fraudulent documents to cover their illegal or ethically questionable activities, "but when's the last time I saw this as a way to raise claims against his or her boss? Never," Bowler added. "It's almost impossible to classify something like this."

Governor's Review

While Bowler has the sole authority to suspend or revoke Duggan's law license, Gov. M. Jodi Rell's office is looking into whether Duggan, who now works for the state Department of Children and Families, can be disciplined as a state employee. Anna Ficeto, the governor's chief legal counsel, conducted a preliminary review and referred the matter to the state Department of Administrative Services for further investigation, said Adam Liegeot, spokesman for the governor. "Governor Rell requested the review to determine what, if any, action would be appropriate under DAS personnel policies," Liegeot said, adding that possible discipline include counseling, a reprimand, a demotion, a suspension, sanctions or dismissal. "DAS officials are reviewing the matter and it would be inappropriate to comment further until the review is complete." Duggan wrote the letter in 2004 when she was a staff lawyer at the Ethics Commission. After it triggered an investigation, Duggan and staff lawyers Alice Sexton and Brenda Bergeron then filed sworn whistle-blower complaints against Plofsky. In those complaints, the women described an unprofessional workplace in which Plofsky referred to female staffers with pet names and encouraged Duggan to leak information to the media that he believed would help him politically but that she believed to be confidential.

Federal Lawsuit

Plofsky eventually was fired. He appealed and was moved to another state job before retiring earlier this year. He is suing the Office of State Ethics in federal court in New Haven over his firing, a case being heard by U.S. District Judge Janet C. Hall. A motion for summary judgment currently is pending, but Duggan's letter has no impact on that matter, said Gregg D. Adler, who is Plofsky's lawyer. The letter, however, could have an impact on a jury. "It's relevant in showing how the final events unfolded that led to Alan's termination," he noted.

In a deposition taken in January for that lawsuit, Duggan, who is now assistant legal director for DCF, revealed the genesis of the process by which Plofsky was removed from office. "I drafted this," she said, answering Adler's question about when she first saw the anonymous letter. "The only bit of good lawyering I did was moving through that answer and not acting surprised," he said. However, from the beginning, "it was really clear that [the letter] wasn't written by a parking lot attendant." Duggan said her husband at the time, Steven M. Regula, a lawyer for Chubb Specialty Insurance in Simsbury, knew about the letter and the work environment Plofsky created. "Ultimately I concluded that I couldn't send" the letter, Duggan said. "When I said I couldn't do this, what I intended to say was that I couldn't go through with going forward in this manner. What [Regula] took it to mean was that I couldn't do it and I needed his help. So he sent the letter."

Duggan and Regula are now divorced. Duggan declined comment for this story, as did her attorney, Hope C. Seeley of Santos & Seeley in Hartford. Regula did not return phone calls for comment. In her affidavit, Duggan said she took no steps to alert any of the ethics commissioners that she had written the letter. She said she was left with no choice but to use the letter to spearhead the investigation into Plofsky's activities. "I felt between a rock and a hard place," she said in her deposition. "I had a family to support and I couldn't walk away from my job. My husband wasn't working at the time. And on the other hand, I was going in to employment where I felt that the conduct and how the office was being run and how I was being treated personally by Mr. Plofsky was becoming increasingly problematic." When asked why she sent a letter supposedly written by a parking lot attendant rather than a letter with her name on it, she said: "I was very concerned for my financial well-being…and safety."

MLK said: "Injustice Anywhere is a Threat to Justice Everywhere"

End Corruption in the Courts!

Court employee, judge or citizen - Report Corruption in any Court Today !! As of June 15, 2016, we've received over 142,500 tips...KEEP THEM COMING !! Email: CorruptCourts@gmail.com

Most Read Stories

- Tembeckjian's Corrupt Judicial 'Ethics' Commission Out of Control

- As NY Judges' Pay Fiasco Grows, Judicial 'Ethics' Chief Enjoys Public-Paid Perks

- New York Judges Disgraced Again

- Wall Street Journal: When our Trusted Officials Lie

- Massive Attorney Conflict in Madoff Scam

- FBI Probes Threats on Federal Witnesses in New York Ethics Scandal

- Federal Judge: "But you destroyed the faith of the people in their government."

- Attorney Gives New Meaning to Oral Argument

- Wannabe Judge Attorney Writes About Ethical Dilemmas SHE Failed to Report

- 3 Judges Covered Crony's 9/11 Donation Fraud

- Former NY State Chief Court Clerk Sues Judges in Federal Court

- Concealing the Truth at the Attorney Ethics Committee

- NY Ethics Scandal Tied to International Espionage Scheme

- Westchester Surrogate's Court's Dastardly Deeds

Monday, June 30, 2008

Lawyer's Phony Letter Could Get Her Disbarred

Sunday, June 29, 2008

Washington Post Editorial: Bias in High Places

Bias in High Places: The Justice Department had a litmus test.

EDITORIAL - The Washington Post - Sunday, June 29, 2008; B06

NOWHERE IS the need for impartial, nonpartisan decision-making more important than at the Justice Department. Charged with enforcing the nation's criminal and civil laws, lawyers in the department must be trusted to apply those laws evenly and without favor. That is one reason the department's policies insist that political affiliation play no role in the hiring of career attorneys. These policies, however, were systematically shredded by some in the Bush administration's Justice Department.

A recently released report by the Justice Department's Office of Inspector General and Office of Professional Responsibility confirmed that in 2002 under Attorney General John D. Ashcroft and again in 2006 under Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales applicants for entry-level positions through the department's honors and summer internship programs were weeded out based on their perceived liberal leanings. The report is one in a series that examines the alleged politicization of the department during the Bush administration. The report focuses much attention on the infractions of two political appointees -- Esther Slater McDonald, then counsel to the associate attorney general, and Michael J. Elston, then chief of staff to Deputy Attorney General Paul J. McNulty. Before 2002, the vetting process for candidates for these programs was handled primarily by career Justice Department employees. In 2006 Mr. Elston was chair of the three-member committee that screened applications for both programs; Ms. McDonald was a member, as was career prosecutor Daniel Fridman, who is praised in the report for reporting violations by Mr. Elston and Ms. McDonald.

How did these two sniff out political proclivities? According to the report, Ms. McDonald searched candidates' applications for " 'leftist commentary and buzzwords' such as 'environmental justice,' 'social justice,' 'making policy,' or 'anything else that involves legislating rather than enforcing' "; she also apparently punished membership in liberal organizations. The report faults Mr. Elston for failing to stop Ms. McDonald's breaches and at times for using political markers to disqualify candidates on his own. The report concludes that both violated Justice Department policy and civil laws, but because they have left the department they can no longer be sanctioned for policy violations, and the department apparently has no standing to bring civil suits for the alleged legal violations. It would be wrong to assume that the Justice Department is now overrun with conservative zealots; most components hire only a handful of entry-level lawyers each year. Attorney General Michael B. Mukasey should be commended for condemning the use of politics in career hiring decisions and revising the selection process to ensure more neutral, merit-based assessments. It is disgraceful that his predecessors did not understand the damage they were doing.

EDITORIAL - The Washington Post - Sunday, June 29, 2008; B06

NOWHERE IS the need for impartial, nonpartisan decision-making more important than at the Justice Department. Charged with enforcing the nation's criminal and civil laws, lawyers in the department must be trusted to apply those laws evenly and without favor. That is one reason the department's policies insist that political affiliation play no role in the hiring of career attorneys. These policies, however, were systematically shredded by some in the Bush administration's Justice Department.

A recently released report by the Justice Department's Office of Inspector General and Office of Professional Responsibility confirmed that in 2002 under Attorney General John D. Ashcroft and again in 2006 under Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales applicants for entry-level positions through the department's honors and summer internship programs were weeded out based on their perceived liberal leanings. The report is one in a series that examines the alleged politicization of the department during the Bush administration. The report focuses much attention on the infractions of two political appointees -- Esther Slater McDonald, then counsel to the associate attorney general, and Michael J. Elston, then chief of staff to Deputy Attorney General Paul J. McNulty. Before 2002, the vetting process for candidates for these programs was handled primarily by career Justice Department employees. In 2006 Mr. Elston was chair of the three-member committee that screened applications for both programs; Ms. McDonald was a member, as was career prosecutor Daniel Fridman, who is praised in the report for reporting violations by Mr. Elston and Ms. McDonald.

How did these two sniff out political proclivities? According to the report, Ms. McDonald searched candidates' applications for " 'leftist commentary and buzzwords' such as 'environmental justice,' 'social justice,' 'making policy,' or 'anything else that involves legislating rather than enforcing' "; she also apparently punished membership in liberal organizations. The report faults Mr. Elston for failing to stop Ms. McDonald's breaches and at times for using political markers to disqualify candidates on his own. The report concludes that both violated Justice Department policy and civil laws, but because they have left the department they can no longer be sanctioned for policy violations, and the department apparently has no standing to bring civil suits for the alleged legal violations. It would be wrong to assume that the Justice Department is now overrun with conservative zealots; most components hire only a handful of entry-level lawyers each year. Attorney General Michael B. Mukasey should be commended for condemning the use of politics in career hiring decisions and revising the selection process to ensure more neutral, merit-based assessments. It is disgraceful that his predecessors did not understand the damage they were doing.

Federal Judge: "The justice system made you a rich man, yet you attempted to corrupt it.”

Judge sentences Scruggs to five years

The Oxford Eagle - Alyssa Schnugg, Staff Writer - June 27, 2008

The Oxford Eagle - Alyssa Schnugg, Staff Writer - June 27, 2008

OXFORD, MISSISSIPPI- Richard Scruggs walked into the courtroom with a smile and a handshake for many in the room. His smile quickly faded as U.S. District Senior Judge Neal Biggers Jr. berated the powerful trial attorney for his actions before sentencing him to five years in prison. Scruggs began to cry, and his body shook as he leaned against his attorney John Keker. A chair was brought over for him to sit while Biggers finished sentencing him. “I couldn’t be more ashamed to be where I am today, to be mixed up in a judicial bribery scheme,” Scruggs said to the court prior to his sentencing. “I disappointed everyone — my wife, my family, my son, my friends ... I deeply regret my conduct ... There’s a scar and a stain on my soul forever.”

Scruggs was charged in November for attempting to bribe Circuit Court Judge Henry Lackey with $40,000 for a favorable ruling in a lawsuit against him. He pleaded guilty to one charge of conspiring to bribe a judge in March. Four others — his son Zach Scruggs, Timothy Balducci, Steven Patterson, and his former law partner Sidney Backstrom — were also charged and have since pleaded guilty. Backstrom’s sentencing was set for 2 this afternoon at the U.S. District Courthouse in Oxford. Biggers spoke to Scruggs for almost 10 minutes, reading parts of the oath lawyers take before becoming a lawyer and calling his crime “one of the worst crimes a lawyer could commit.” “This is very unpleasant for me,” Biggers said. “You not only attempted to bribe the court, but you violated the oath. ... You found out Judge Lackey is not a man to bribe. The justice system made you a rich man, yet you attempted to corrupt it.”

Scruggs was given a $250,000 fine and must report to prison by Aug. 4. He will afterward serve three years of supervised probation. Keker asked Biggers to recommend Scruggs serve his time at the Federal Prison Camp in Pensacola, Fla., since they have family there and it would make it easier for Scruggs’ wife, Diane, to visit him. Biggers obliged. “Best of luck to you,” were Biggers’ final words to Scruggs. Part of Scruggs’ plea agreement he signed in March capped the possible prison sentence at 60 months. Backstrom is expected to receive a 30-month sentence, since his plea agreement stated he could receive up to half of whatever sentence Scruggs received. The younger Scruggs is set for sentencing on July 2. Balducci and Patterson have not yet received sentencing dates.

End of a career

After establishing his small practice in Pascagoula, Scruggs gained national attention for earning millions of dollars from asbestos litigation and for his role in a multibillion-dollar settlement with tobacco companies in the mid-1990s. His meteoric rise in the legal profession and his sudden wealth was a story that could have been scripted by Hollywood — a fact emphasized when his case against the tobacco companies was made a central part of the 1999 movie “The Insider,” starring Al Pacino and Russell Crowe. An actor portrayed Scruggs in the movie, and some scenes were filmed at Scruggs’ home in Pascagoula. Scruggs, whose brother-in-law is former U.S. Sen. Trent Lott, moved his home and his practice from the Gulf Coast to Oxford about three years ago. He invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in renovations to his office over looking the Square and in the new home he is building around the corner from William Faulkner’s Rowan Oak.

Scruggs sued State Farm Insurance on behalf of hundreds of policyholders whose claims had been denied by insurance companies after their homes were destroyed in Hurricane Katrina. Scruggs put together a legal team, called the Scruggs Katrina Group, to represent the policyholders in the court battle against the insurance companies. One of the firms brought in to work with Scruggs was Jones, Funderburg, Sessums, Peterson & Lee, a law firm based in Jackson.

After the legal team reached a settlement with State Farm Insurance Cos. in January 2007, a dispute over how the $26.5 million in legal fees would be distributed to the firms erupted between the Jones law firm and the other members of the Scruggs Katrina Group. The Jones firm was kicked out of the legal team and, after attempts to resolve the compensation dispute failed, the Jones firm took the unusual step of filing a lawsuit against the other members of the legal team. The Jones firm, led by attorney John G. Jones, filed a civil lawsuit, Jones, et all. v. Scruggs, et al, in the Lafayette County Circuit Court in March 2007. The Jackson firm hired the Tollison Law Firm in Oxford to represent them in the litigation. That’s when Scruggs and the other four men indicted in November 2007 allegedly hatched a plan to bribe Lackey to issue a ruling in this legal dispute in their favor, according to the indictment.

Not over yet

Scruggs is still being investigated in the alleged attempted bribing of Hinds County Court Judge Bobby DeLaughter. According to court records, Scruggs used his influence with Lott to dangle the possibility of a federal judge appointment in front of DeLaughter if he ruled favorably in a lawsuit against Scruggs — Wilson v. Scruggs. Attorney Joey Langston has been indicted in that case and has pleaded guilty. He is awaiting sentencing. No other charges have been filed in that case thus far.

Scruggs was charged in November for attempting to bribe Circuit Court Judge Henry Lackey with $40,000 for a favorable ruling in a lawsuit against him. He pleaded guilty to one charge of conspiring to bribe a judge in March. Four others — his son Zach Scruggs, Timothy Balducci, Steven Patterson, and his former law partner Sidney Backstrom — were also charged and have since pleaded guilty. Backstrom’s sentencing was set for 2 this afternoon at the U.S. District Courthouse in Oxford. Biggers spoke to Scruggs for almost 10 minutes, reading parts of the oath lawyers take before becoming a lawyer and calling his crime “one of the worst crimes a lawyer could commit.” “This is very unpleasant for me,” Biggers said. “You not only attempted to bribe the court, but you violated the oath. ... You found out Judge Lackey is not a man to bribe. The justice system made you a rich man, yet you attempted to corrupt it.”

Scruggs was given a $250,000 fine and must report to prison by Aug. 4. He will afterward serve three years of supervised probation. Keker asked Biggers to recommend Scruggs serve his time at the Federal Prison Camp in Pensacola, Fla., since they have family there and it would make it easier for Scruggs’ wife, Diane, to visit him. Biggers obliged. “Best of luck to you,” were Biggers’ final words to Scruggs. Part of Scruggs’ plea agreement he signed in March capped the possible prison sentence at 60 months. Backstrom is expected to receive a 30-month sentence, since his plea agreement stated he could receive up to half of whatever sentence Scruggs received. The younger Scruggs is set for sentencing on July 2. Balducci and Patterson have not yet received sentencing dates.

End of a career

After establishing his small practice in Pascagoula, Scruggs gained national attention for earning millions of dollars from asbestos litigation and for his role in a multibillion-dollar settlement with tobacco companies in the mid-1990s. His meteoric rise in the legal profession and his sudden wealth was a story that could have been scripted by Hollywood — a fact emphasized when his case against the tobacco companies was made a central part of the 1999 movie “The Insider,” starring Al Pacino and Russell Crowe. An actor portrayed Scruggs in the movie, and some scenes were filmed at Scruggs’ home in Pascagoula. Scruggs, whose brother-in-law is former U.S. Sen. Trent Lott, moved his home and his practice from the Gulf Coast to Oxford about three years ago. He invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in renovations to his office over looking the Square and in the new home he is building around the corner from William Faulkner’s Rowan Oak.

Scruggs sued State Farm Insurance on behalf of hundreds of policyholders whose claims had been denied by insurance companies after their homes were destroyed in Hurricane Katrina. Scruggs put together a legal team, called the Scruggs Katrina Group, to represent the policyholders in the court battle against the insurance companies. One of the firms brought in to work with Scruggs was Jones, Funderburg, Sessums, Peterson & Lee, a law firm based in Jackson.

After the legal team reached a settlement with State Farm Insurance Cos. in January 2007, a dispute over how the $26.5 million in legal fees would be distributed to the firms erupted between the Jones law firm and the other members of the Scruggs Katrina Group. The Jones firm was kicked out of the legal team and, after attempts to resolve the compensation dispute failed, the Jones firm took the unusual step of filing a lawsuit against the other members of the legal team. The Jones firm, led by attorney John G. Jones, filed a civil lawsuit, Jones, et all. v. Scruggs, et al, in the Lafayette County Circuit Court in March 2007. The Jackson firm hired the Tollison Law Firm in Oxford to represent them in the litigation. That’s when Scruggs and the other four men indicted in November 2007 allegedly hatched a plan to bribe Lackey to issue a ruling in this legal dispute in their favor, according to the indictment.

Not over yet

Scruggs is still being investigated in the alleged attempted bribing of Hinds County Court Judge Bobby DeLaughter. According to court records, Scruggs used his influence with Lott to dangle the possibility of a federal judge appointment in front of DeLaughter if he ruled favorably in a lawsuit against Scruggs — Wilson v. Scruggs. Attorney Joey Langston has been indicted in that case and has pleaded guilty. He is awaiting sentencing. No other charges have been filed in that case thus far.

Saturday, June 28, 2008

Federal Judge Bribery Scheme Gets Lawyer 5 Years

High-Profile Attorney Gets 5 Years For Judicial Bribery Scheme

New York Lawyer by Holbrook Mohr, Associated Press Writer - June 27, 2008

OXFORD, Miss. - Richard "Dickie" Scruggs, the attorney who built his career by taking on tobacco, asbestos and insurance companies, was sentenced Friday to five years in prison for conspiring to bribe a judge. U.S. District Judge Neal Biggers Jr. called Scruggs' conduct "reprehensible" and fined him $250,000. The judge handed down the full sentence requested by prosecutors despite arguments from the defense for half that time in prison. Scruggs appeared to nearly faint as the federal judge scolded him for his conduct. Some people in the courtroom gasped as Scruggs started to sway side to side and his attorney grabbed his arm to steady him. He had to be seated before the sentence was read. "I could not be more ashamed where I am today, mixed up in a judicial bribery scheme," Scruggs told the judge. Scruggs must report to prison by Aug. 4 and pay the fine in one lump sum within 30 days. Scruggs gained fame in the 1990s by using a corporate insider against tobacco companies in lawsuits that resulted in a $206 billion settlement. That case was portrayed in the 1999 film "The Insider."

Scruggs was indicted in November along with his son and a law partner after an associate wore a wire for the FBI and secretly recorded conversations about the alleged bribery. Scruggs initially denied wrongdoing. But in March, Scruggs and former law partner Sidney Backstrom pleaded guilty to conspiring to bribe Lafayette County Circuit Court Judge Henry Lackey with $50,000. Prosecutors say Scruggs wanted a favorable ruling in a dispute over $26.5 million in legal fees from a mass settlement of Hurricane Katrina insurance cases. Scruggs' son, Zach Scruggs, pleaded guilty to misprision of a felony, meaning he knew a crime was committed but didn't report it. He is to be sentenced next week. Many high-profile friends had sought leniency for Scruggs in letters to the federal judge, including Former "60 Minutes" producer Lowell Bergman and tobacco industry whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand, both portrayed in "The Insider."

New York Lawyer by Holbrook Mohr, Associated Press Writer - June 27, 2008

OXFORD, Miss. - Richard "Dickie" Scruggs, the attorney who built his career by taking on tobacco, asbestos and insurance companies, was sentenced Friday to five years in prison for conspiring to bribe a judge. U.S. District Judge Neal Biggers Jr. called Scruggs' conduct "reprehensible" and fined him $250,000. The judge handed down the full sentence requested by prosecutors despite arguments from the defense for half that time in prison. Scruggs appeared to nearly faint as the federal judge scolded him for his conduct. Some people in the courtroom gasped as Scruggs started to sway side to side and his attorney grabbed his arm to steady him. He had to be seated before the sentence was read. "I could not be more ashamed where I am today, mixed up in a judicial bribery scheme," Scruggs told the judge. Scruggs must report to prison by Aug. 4 and pay the fine in one lump sum within 30 days. Scruggs gained fame in the 1990s by using a corporate insider against tobacco companies in lawsuits that resulted in a $206 billion settlement. That case was portrayed in the 1999 film "The Insider."

Scruggs was indicted in November along with his son and a law partner after an associate wore a wire for the FBI and secretly recorded conversations about the alleged bribery. Scruggs initially denied wrongdoing. But in March, Scruggs and former law partner Sidney Backstrom pleaded guilty to conspiring to bribe Lafayette County Circuit Court Judge Henry Lackey with $50,000. Prosecutors say Scruggs wanted a favorable ruling in a dispute over $26.5 million in legal fees from a mass settlement of Hurricane Katrina insurance cases. Scruggs' son, Zach Scruggs, pleaded guilty to misprision of a felony, meaning he knew a crime was committed but didn't report it. He is to be sentenced next week. Many high-profile friends had sought leniency for Scruggs in letters to the federal judge, including Former "60 Minutes" producer Lowell Bergman and tobacco industry whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand, both portrayed in "The Insider."

Friday, June 27, 2008

Kaye Scholer Hit with Malpractice Suit

Suit Against Kaye Scholer Alleges Discovery Foul-ups

The New York Law Journal by Anthony Lin - June 27, 2008

Kaye Scholer has been hit with a legal malpractice suit by a former client that claims the New York law firm's discovery mistakes forced it to enter into a $107 million antitrust settlement. Dallas-based chemical and plastics giant Celanese Corp. announced June 13 it was paying that amount to resolve multi-district litigation brought in federal court in North Carolina by several textile manufacturers that had accused the company of fixing prices in the market for polyester staple fibers. Kaye Scholer had represented Celanese in the disputes from March 2002 to July 2006. In a 33-page amended complaint filed Wednesday in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, Celanese said it only paid such a large settlement because Kaye Scholer's failure to turn over hundreds of thousands of documents to the plaintiffs had exposed Celanese to draconian trial sanctions. "The negligence and malpractice of Kaye Scholer and the consequences of that negligence caused the chances of Celanese's prevailing at trial to decrease dramatically," the company said.

Celanese originally filed its complaint in Texas state court but the suit was removed to federal court. In addition to the firm itself, Celanese also names as individual defendants Kaye Scholer partner and executive committee member Michael D. Blechman and former special counsel Robert B. Bernstein. Celanese claims it would have only paid a nuisance settlement without the threat of sanctions but for Kaye Scholer's errors. It is asking in damages the difference between that nominal amount and the $107 million it paid. A spokesman for Kaye Scholer declined comment yesterday, citing a firm policy against discussing active litigation. However, the firm filed its own lawsuit against Celanese last week, seeking alleged unpaid legal fees as well as a declaratory judgment that Kaye Scholer's work met professional standards. "There is a bona fide dispute and actual controversy among the parties concerning the extent to which Kaye Scholer's legal services to the Celanese Entities were in accordance with the standards of care ordinarily provided by professionals providing legal representation and consistent with any fiduciary duty owed to the Celanese Entities," the firm said in its complaint.

Celanese claims that it and another of its law firms, Baker Botts, advised Kayer Scholer of the existence of 20,000 boxes of documents in a facility in Hillside, N.J., possibly relating to the polyester staple fiber market. Kaye Scholer lawyers, the complaint says, were also aware of responsive documents contained in a 3,000-roll microfilm archive, as well as additional responsive documents stored in North Carolina, Virginia and Mexico. But, according to the suit, Kaye Scholer only produced 220 pages of documents in response to the antitrust plaintiffs' document requests, repeatedly representing that those were the only relevant documents in Celanese's possession. At a June 6, 2006, hearing, the judge overseeing the antitrust case, Judge Richard L. Voorhees of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of North Carolina, took Celanese to task for "the trove of documents it held in the wings just out of sight" and said the company had been playing "cat and mouse" with the court and plaintiffs. According to malpractice suit, Judge Voorhees sanctioned Celanese $114,000 in fees and expenses, and said he would consider further sanctions on evaluating the impact of the discovery misconduct.

The judge also reserved ruling on an October 2006 sanctions motion by plaintiffs asking for a range of findings against Celanese, including that the company acted in bad faith that an adverse inference should be drawn against it on key issues and that the company should be prevented from presenting evidence on certain issues. Celanese said in its suit that the prospect of such sanctions, which would have severely hampered its ability to defend itself at trial, forced it to enter into a settlement in May. The company fired Kaye Scholer in July 2006 and hired Hector Torres of Kasowitz, Benson, Torres & Friedman to continue to represent it. The Kasowitz firm is also representing Celanese in its suit against Kaye Scholer. Trial sanctions over discovery foul-ups have been a major area of concerns for litigants and their lawyers in recent years. A sanction instructing a jury to draw an adverse inference led to a $1.6 billion verdict against Morgan Stanley in a high-profile suit in Florida state court. But that award was later overturned on appeal. - Anthony Lin can be reached at alin@alm.com.

The New York Law Journal by Anthony Lin - June 27, 2008

Kaye Scholer has been hit with a legal malpractice suit by a former client that claims the New York law firm's discovery mistakes forced it to enter into a $107 million antitrust settlement. Dallas-based chemical and plastics giant Celanese Corp. announced June 13 it was paying that amount to resolve multi-district litigation brought in federal court in North Carolina by several textile manufacturers that had accused the company of fixing prices in the market for polyester staple fibers. Kaye Scholer had represented Celanese in the disputes from March 2002 to July 2006. In a 33-page amended complaint filed Wednesday in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, Celanese said it only paid such a large settlement because Kaye Scholer's failure to turn over hundreds of thousands of documents to the plaintiffs had exposed Celanese to draconian trial sanctions. "The negligence and malpractice of Kaye Scholer and the consequences of that negligence caused the chances of Celanese's prevailing at trial to decrease dramatically," the company said.

Celanese originally filed its complaint in Texas state court but the suit was removed to federal court. In addition to the firm itself, Celanese also names as individual defendants Kaye Scholer partner and executive committee member Michael D. Blechman and former special counsel Robert B. Bernstein. Celanese claims it would have only paid a nuisance settlement without the threat of sanctions but for Kaye Scholer's errors. It is asking in damages the difference between that nominal amount and the $107 million it paid. A spokesman for Kaye Scholer declined comment yesterday, citing a firm policy against discussing active litigation. However, the firm filed its own lawsuit against Celanese last week, seeking alleged unpaid legal fees as well as a declaratory judgment that Kaye Scholer's work met professional standards. "There is a bona fide dispute and actual controversy among the parties concerning the extent to which Kaye Scholer's legal services to the Celanese Entities were in accordance with the standards of care ordinarily provided by professionals providing legal representation and consistent with any fiduciary duty owed to the Celanese Entities," the firm said in its complaint.

Celanese claims that it and another of its law firms, Baker Botts, advised Kayer Scholer of the existence of 20,000 boxes of documents in a facility in Hillside, N.J., possibly relating to the polyester staple fiber market. Kaye Scholer lawyers, the complaint says, were also aware of responsive documents contained in a 3,000-roll microfilm archive, as well as additional responsive documents stored in North Carolina, Virginia and Mexico. But, according to the suit, Kaye Scholer only produced 220 pages of documents in response to the antitrust plaintiffs' document requests, repeatedly representing that those were the only relevant documents in Celanese's possession. At a June 6, 2006, hearing, the judge overseeing the antitrust case, Judge Richard L. Voorhees of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of North Carolina, took Celanese to task for "the trove of documents it held in the wings just out of sight" and said the company had been playing "cat and mouse" with the court and plaintiffs. According to malpractice suit, Judge Voorhees sanctioned Celanese $114,000 in fees and expenses, and said he would consider further sanctions on evaluating the impact of the discovery misconduct.

The judge also reserved ruling on an October 2006 sanctions motion by plaintiffs asking for a range of findings against Celanese, including that the company acted in bad faith that an adverse inference should be drawn against it on key issues and that the company should be prevented from presenting evidence on certain issues. Celanese said in its suit that the prospect of such sanctions, which would have severely hampered its ability to defend itself at trial, forced it to enter into a settlement in May. The company fired Kaye Scholer in July 2006 and hired Hector Torres of Kasowitz, Benson, Torres & Friedman to continue to represent it. The Kasowitz firm is also representing Celanese in its suit against Kaye Scholer. Trial sanctions over discovery foul-ups have been a major area of concerns for litigants and their lawyers in recent years. A sanction instructing a jury to draw an adverse inference led to a $1.6 billion verdict against Morgan Stanley in a high-profile suit in Florida state court. But that award was later overturned on appeal. - Anthony Lin can be reached at alin@alm.com.

Thursday, June 26, 2008

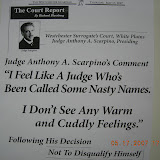

Complaints Against New York Judges Reach a High

Complaints Against New York Judges Reach a High, but Fewer Merit Investigations

The New York Times by JOHN ELIGON - June 26, 2008

A record number of complaints were filed against New York State judges in 2007, according to a report by the State Commission on Judicial Conduct. But the number of complaints that warranted a full investigation during that time was lower than it had been in a decade, the report said.

The commission, which has been collecting grievances since 1975, submitted the report to the State Legislature last month. It encompasses all of the state’s roughly 3,500 judges, including Supreme Court justices, city and county court judges, and justices in villages and towns. There were 1,711 complaints filed against judges last year, the report said. That number is up from the previous high over the past decade: 1,565 complaints in 2005. Nearly 1,300 of the 2007 complaints were found to have no basis and were dismissed almost immediately, while more than 400 others were sent on for preliminary inquiries. The commission found 192 of the complaints to be potentially valid and sent them on for full-fledged inquiries. The last time that fewer than 200 complaints were sent on for full investigation was in 1997, when there were 172.

“I think that the fact that there is less substantiated wrongdoing shows that the judges are doing an outstanding job,” said David Bookstaver, a spokesman for the Office of the Court Administration. Five judges were removed last year, 10 were censured and 9 admonished. But some of those punishments were the result of complaints pending prior to 2007. The record number of complaints was more indicative of the public’s increased awareness of the commission’s duties, not the performance of judges, said Robert H. Tembeckjian, the administrator of the agency. Mr. Tembeckjian cited several reasons for the commission’s increased exposure, including wider use of the Internet and reports in the news media.

He cited a series in The New York Times in 2006 that found a long history of judicial misconduct and poor training in small-town courts in New York. Mr. Tembeckjian also mentioned several instances of judicial misconduct that were widely publicized. Last November, Robert M. Restaino, a judge on the Niagara Falls City Court, was removed for sending 46 defendants who sat in his courtroom into police custody after no one took responsibility for a cellphone that rang in the courtroom. Mr. Tembeckjian said he received media inquiries in that case from around the globe. As people see the commission acting on judicial misconduct, Mr. Tembeckjian said, they become more inclined to file complaints.

“As the public and civic organizations and lawyers become more confident and satisfied that the commission will seriously treat their complaints,” Mr. Tembeckjian said, “there tends to be more public confidence in the commission’s discharge of its responsibilities.” In more than half the cases last year — 941 — the complaints were about a judge’s decision. Those complaints were immediately dismissed because that is an issue for an appellate court, Mr. Tembeckjian said. A judge’s demeanor drew the second most number of complaints last year with 235, the report said. The subject of other complaints include claims of delays, conflicts of interest, bias, corruption and intoxication.

The New York Times by JOHN ELIGON - June 26, 2008

A record number of complaints were filed against New York State judges in 2007, according to a report by the State Commission on Judicial Conduct. But the number of complaints that warranted a full investigation during that time was lower than it had been in a decade, the report said.

The commission, which has been collecting grievances since 1975, submitted the report to the State Legislature last month. It encompasses all of the state’s roughly 3,500 judges, including Supreme Court justices, city and county court judges, and justices in villages and towns. There were 1,711 complaints filed against judges last year, the report said. That number is up from the previous high over the past decade: 1,565 complaints in 2005. Nearly 1,300 of the 2007 complaints were found to have no basis and were dismissed almost immediately, while more than 400 others were sent on for preliminary inquiries. The commission found 192 of the complaints to be potentially valid and sent them on for full-fledged inquiries. The last time that fewer than 200 complaints were sent on for full investigation was in 1997, when there were 172.

“I think that the fact that there is less substantiated wrongdoing shows that the judges are doing an outstanding job,” said David Bookstaver, a spokesman for the Office of the Court Administration. Five judges were removed last year, 10 were censured and 9 admonished. But some of those punishments were the result of complaints pending prior to 2007. The record number of complaints was more indicative of the public’s increased awareness of the commission’s duties, not the performance of judges, said Robert H. Tembeckjian, the administrator of the agency. Mr. Tembeckjian cited several reasons for the commission’s increased exposure, including wider use of the Internet and reports in the news media.

He cited a series in The New York Times in 2006 that found a long history of judicial misconduct and poor training in small-town courts in New York. Mr. Tembeckjian also mentioned several instances of judicial misconduct that were widely publicized. Last November, Robert M. Restaino, a judge on the Niagara Falls City Court, was removed for sending 46 defendants who sat in his courtroom into police custody after no one took responsibility for a cellphone that rang in the courtroom. Mr. Tembeckjian said he received media inquiries in that case from around the globe. As people see the commission acting on judicial misconduct, Mr. Tembeckjian said, they become more inclined to file complaints.

“As the public and civic organizations and lawyers become more confident and satisfied that the commission will seriously treat their complaints,” Mr. Tembeckjian said, “there tends to be more public confidence in the commission’s discharge of its responsibilities.” In more than half the cases last year — 941 — the complaints were about a judge’s decision. Those complaints were immediately dismissed because that is an issue for an appellate court, Mr. Tembeckjian said. A judge’s demeanor drew the second most number of complaints last year with 235, the report said. The subject of other complaints include claims of delays, conflicts of interest, bias, corruption and intoxication.

Court Revives Malpractice Suit Against NY Firm

Court Revives Malpractice Suit Against NY Firm

The New York Law Journal by Anthony Lin - June 26, 2008

The Court of Appeals yesterday revived a legal malpractice suit against law firm Larossa, Mitchell & Ross over its representation of a personal injury lawyer found to have defrauded New York City by fabricating evidence in tort cases. The suit, which was previously dismissed because Larossa's ex-client was in dissolution, cannot now be barred on res judicata grounds against a successor firm, the court ruled. The case stems from the travails of the law firm Morris J. Eisen PC. Once one of the New York's top personal injury firms, the firm was accused by the city of falsifying evidence in a 1986 civil suit. Seven lawyers and investigators for the firm, including Morris J. Eisen, were subsequently targeted by federal prosecutors in Brooklyn and convicted on Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act charges in 1991. Mr. Eisen had been represented in the criminal case by James M. Larossa, and the Larossa firm also represented the Eisen firm in the civil suit by the city. Eisen first tried to bring a legal malpractice suit against Larossa after a court granted partial summary judgment to the city on its fraud claims. The city was awarded $2.1 million.

The suit claimed Larossa did not adequately oppose the city's summary judgment motion, failing to present evidence that would have shown that, notwithstanding any false testimony, the city was actually responsible for the injuries in the cases at issue. Eisen's complaint was dismissed in January 2000 on the grounds that the firm was a dissolved professional corporation for failure to pay its franchise taxes, and it lacked capacity to bring the suit. A successor firm, Landau, with Mr. Eisen as an assignee, filed an identical suit, but it was barred on res judicata grounds. The Court of Appeals reversed. In a decision written by Judge Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick, the Court said the dismissal without prejudice in Landau v. Larossa, Mitchell & Ross, 604476/01, "lacks a necessary element of res judicata - by its terms such a judgment is not a final determination on the merits." The Court noted that only the issues of Eisen and Landau's standing and capacity had thus far been litigated.

"We remain mindful that if applied too rigidly, res judicata has the potential to work considerable injustice," the Court said, adding that "Landau has yet to have its day in court to litigate the merits of its legal malpractice claim against defendants and we therefore find that res judicata is not applicable to plaintiff in this case." Mr. Eisen was represented in the appeal by John P. Coffey of Bernstein Litowitz Berger & Grossman, who said he was very pleased Mr. Eisen would get to litigate his claims after "many, many years." Larossa was represented by Nancy A. Breslow of Martin, Clearwater & Bell. The accusations and subsequent prosecution of Mr. Eisen was a major scandal in the legal community at the time. In one case, the personal injury lawyers put on one witness who was in jail at the time of the accident he apparently saw. They also once used a pickax to enlarge a pothole for a photograph to be used as a trial exhibit. But Mr. Coffey said yesterday that Mr. Eisen was found guilty for the actions of his underlings and noted that he was dropped as an individual defendant from the city suit.

The New York Law Journal by Anthony Lin - June 26, 2008

The Court of Appeals yesterday revived a legal malpractice suit against law firm Larossa, Mitchell & Ross over its representation of a personal injury lawyer found to have defrauded New York City by fabricating evidence in tort cases. The suit, which was previously dismissed because Larossa's ex-client was in dissolution, cannot now be barred on res judicata grounds against a successor firm, the court ruled. The case stems from the travails of the law firm Morris J. Eisen PC. Once one of the New York's top personal injury firms, the firm was accused by the city of falsifying evidence in a 1986 civil suit. Seven lawyers and investigators for the firm, including Morris J. Eisen, were subsequently targeted by federal prosecutors in Brooklyn and convicted on Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act charges in 1991. Mr. Eisen had been represented in the criminal case by James M. Larossa, and the Larossa firm also represented the Eisen firm in the civil suit by the city. Eisen first tried to bring a legal malpractice suit against Larossa after a court granted partial summary judgment to the city on its fraud claims. The city was awarded $2.1 million.

The suit claimed Larossa did not adequately oppose the city's summary judgment motion, failing to present evidence that would have shown that, notwithstanding any false testimony, the city was actually responsible for the injuries in the cases at issue. Eisen's complaint was dismissed in January 2000 on the grounds that the firm was a dissolved professional corporation for failure to pay its franchise taxes, and it lacked capacity to bring the suit. A successor firm, Landau, with Mr. Eisen as an assignee, filed an identical suit, but it was barred on res judicata grounds. The Court of Appeals reversed. In a decision written by Judge Carmen Beauchamp Ciparick, the Court said the dismissal without prejudice in Landau v. Larossa, Mitchell & Ross, 604476/01, "lacks a necessary element of res judicata - by its terms such a judgment is not a final determination on the merits." The Court noted that only the issues of Eisen and Landau's standing and capacity had thus far been litigated.

"We remain mindful that if applied too rigidly, res judicata has the potential to work considerable injustice," the Court said, adding that "Landau has yet to have its day in court to litigate the merits of its legal malpractice claim against defendants and we therefore find that res judicata is not applicable to plaintiff in this case." Mr. Eisen was represented in the appeal by John P. Coffey of Bernstein Litowitz Berger & Grossman, who said he was very pleased Mr. Eisen would get to litigate his claims after "many, many years." Larossa was represented by Nancy A. Breslow of Martin, Clearwater & Bell. The accusations and subsequent prosecution of Mr. Eisen was a major scandal in the legal community at the time. In one case, the personal injury lawyers put on one witness who was in jail at the time of the accident he apparently saw. They also once used a pickax to enlarge a pothole for a photograph to be used as a trial exhibit. But Mr. Coffey said yesterday that Mr. Eisen was found guilty for the actions of his underlings and noted that he was dropped as an individual defendant from the city suit.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

Committee On Attorney Conduct Selects Chairman of Search Committee

Litigation Recovery Trust

515 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022

Tel: 347-632-9775 email: lrtinformation@gmail.com

Fax: 801-926-9269 email: pcacinformation@gmail.com

PRESS RELEASE

For Immediate Release

Ad Hoc Public Committee On Attorney Conduct Selects John T. Whitely As Chairman of Executive Search Committee

PCAC Formed To Review Actions Of New York State Ethics Committees Moves to Recruit Members As First Step to Replace Existing Grievance Committee Structures

New York, NY - The Ad Hoc Public Committee On Attorney Conduct (PCAC) has announced the appointment of John T. Whitely as chairman of the PCAC Executive Search Committee. The PCAC was recently established by joint action of Litigation Recovery Trust, a New York based rights administration organization, and Integrity in the Courts and Expose Corrupt Courts, two Internet blogs focused on judicial and attorney disciplinary process and procedures. The objective of the new organization is to oversee New York State’s Attorney Disciplinary Committees. The Ad Hoc bar oversight committee is being headquartered in New York City.

In announcing the appointment of the search committee, William J. Hallenbeck, executive director of Litigation Recovery Trust, stated that efforts were being made to accelerate the establishment of the PCAC as a direct result of the continued filing of a growing number of federal lawsuits against the statewide attorney grievance committees and their parent organization, New York State Office of Court Administration. Mr. Hallenbeck noted, “As legal actions against the attorney disciplinary committees continue to multiply, it is clear that timing has now become a critical issue. We must move forward expeditiously to organize PCAC so that it can undertake a detailed review of the fatally flawed system, which allows attorneys in New York to oversee, protect and cover-up the unethical and often illegal conduct of their fellow lawyers.”

Mr. Hallenbeck continued, “ A former long time executive vice president of Grace & Company, and president - CEO of Amerace and Federation Chemical, both New York Stock Exchange registered companies, Jack Whitely brings decades of practical, high-level executive experience to the task of organizing the PCAC organization.” Mr. Whitely is a graduate of Notre Dame University and its law school.

In accepting the appointment, Mr. Whitely noted, “The well documented complaints of malpractice, personal attacks and even theft that have recently been filed with the federal courts against grievance committee executive staff, and individual lawyers allegedly shielded by the disciplinary committee process, reflects a system totally out of control and beyond repair. I look forward to assisting PCAC to speed the establishment of a new structure under which the public will become the controlling part of the lawyer oversight process.”

Expose Corrupt Courts blog issued the following statement: “We are gratified that Jack Whitely has agreed to assist with recruitment of PCAC members. What is sought is a committee made up of members with broad and diverse business experience and expertise, as well as impeccable records of fairness and sound judgment to review breaches of attorney ethics and past rulings which can be classified as highly suspect.”

Under the plan put forth by LRT, Integrity in the Courts. and Expose Corrupt Courts, the newly formed Public Committee On Attorney Conduct will review both past and present cases brought before the grievance committees to provide an independent review and analysis of the facts, and issue proposed findings. With respect to past cases, the committee will be particularly interested in hearing from persons who maintain that they have been treated unfairly and unjustly by the disciplinary committees. As part of its initial efforts, the new committee will actively seek documentation of all complaints against any attorneys dating to January 1, 1988.

According to the founding organizations, the Public Committee On Attorney Conduct will include as members individuals, who through their personal and professional lives have established a reputation of responsibility and fairness. While attorneys will be available to the PCAC as advisers, all voting members issuing formal reports and decisions will be non attorneys.

In commenting on the structure of the ad hoc committee, Mr. Hallenbeck noted that this will be the first time in the United States that a review body made up entirely of non attorneys will be assembled to investigate and practicing lawyers. He added, “By initially establishing a parallel committee structure to the New York State grievance committees, we will have the opportunity to determine that a bar review process made up entirely of non attorneys can achieve the desired result. We should make it clear that our immediate goal here is to create a practical, working model to replace the attorney grievance committees.”

Mr. Hallenbeck also reported that since news of the formation of the PCAC was first made public on June 17, individual complainants have begun submitting requests to PCAC to review both past and current matters before the New York State grievance committees. Requests and documents are being received by PCAC at its email address: pcacinformation @gmail.com. Telephone inquiries can be directed to 347-632-9775 .For additional information, contact the PCAC website at www.pcac.8k.com.

#### 30 ####

For additional information please contact:

515 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022

Tel: 347-632-9775 email: lrtinformation@gmail.com

Fax: 801-926-9269 email: pcacinformation@gmail.com

PRESS RELEASE

For Immediate Release

Ad Hoc Public Committee On Attorney Conduct Selects John T. Whitely As Chairman of Executive Search Committee

PCAC Formed To Review Actions Of New York State Ethics Committees Moves to Recruit Members As First Step to Replace Existing Grievance Committee Structures

New York, NY - The Ad Hoc Public Committee On Attorney Conduct (PCAC) has announced the appointment of John T. Whitely as chairman of the PCAC Executive Search Committee. The PCAC was recently established by joint action of Litigation Recovery Trust, a New York based rights administration organization, and Integrity in the Courts and Expose Corrupt Courts, two Internet blogs focused on judicial and attorney disciplinary process and procedures. The objective of the new organization is to oversee New York State’s Attorney Disciplinary Committees. The Ad Hoc bar oversight committee is being headquartered in New York City.

In announcing the appointment of the search committee, William J. Hallenbeck, executive director of Litigation Recovery Trust, stated that efforts were being made to accelerate the establishment of the PCAC as a direct result of the continued filing of a growing number of federal lawsuits against the statewide attorney grievance committees and their parent organization, New York State Office of Court Administration. Mr. Hallenbeck noted, “As legal actions against the attorney disciplinary committees continue to multiply, it is clear that timing has now become a critical issue. We must move forward expeditiously to organize PCAC so that it can undertake a detailed review of the fatally flawed system, which allows attorneys in New York to oversee, protect and cover-up the unethical and often illegal conduct of their fellow lawyers.”

Mr. Hallenbeck continued, “ A former long time executive vice president of Grace & Company, and president - CEO of Amerace and Federation Chemical, both New York Stock Exchange registered companies, Jack Whitely brings decades of practical, high-level executive experience to the task of organizing the PCAC organization.” Mr. Whitely is a graduate of Notre Dame University and its law school.

In accepting the appointment, Mr. Whitely noted, “The well documented complaints of malpractice, personal attacks and even theft that have recently been filed with the federal courts against grievance committee executive staff, and individual lawyers allegedly shielded by the disciplinary committee process, reflects a system totally out of control and beyond repair. I look forward to assisting PCAC to speed the establishment of a new structure under which the public will become the controlling part of the lawyer oversight process.”

Expose Corrupt Courts blog issued the following statement: “We are gratified that Jack Whitely has agreed to assist with recruitment of PCAC members. What is sought is a committee made up of members with broad and diverse business experience and expertise, as well as impeccable records of fairness and sound judgment to review breaches of attorney ethics and past rulings which can be classified as highly suspect.”

Under the plan put forth by LRT, Integrity in the Courts. and Expose Corrupt Courts, the newly formed Public Committee On Attorney Conduct will review both past and present cases brought before the grievance committees to provide an independent review and analysis of the facts, and issue proposed findings. With respect to past cases, the committee will be particularly interested in hearing from persons who maintain that they have been treated unfairly and unjustly by the disciplinary committees. As part of its initial efforts, the new committee will actively seek documentation of all complaints against any attorneys dating to January 1, 1988.

According to the founding organizations, the Public Committee On Attorney Conduct will include as members individuals, who through their personal and professional lives have established a reputation of responsibility and fairness. While attorneys will be available to the PCAC as advisers, all voting members issuing formal reports and decisions will be non attorneys.

In commenting on the structure of the ad hoc committee, Mr. Hallenbeck noted that this will be the first time in the United States that a review body made up entirely of non attorneys will be assembled to investigate and practicing lawyers. He added, “By initially establishing a parallel committee structure to the New York State grievance committees, we will have the opportunity to determine that a bar review process made up entirely of non attorneys can achieve the desired result. We should make it clear that our immediate goal here is to create a practical, working model to replace the attorney grievance committees.”

Mr. Hallenbeck also reported that since news of the formation of the PCAC was first made public on June 17, individual complainants have begun submitting requests to PCAC to review both past and current matters before the New York State grievance committees. Requests and documents are being received by PCAC at its email address: pcacinformation @gmail.com. Telephone inquiries can be directed to 347-632-9775 .For additional information, contact the PCAC website at www.pcac.8k.com.

#### 30 ####

For additional information please contact:

William J. Hollenbeck

Executive Director

Litigation Recovery Trust

515 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 10022

Telephone 6462019269

E-mail: lrtinformation@gmail.com

Web: litigationrecoverytrust.8k.com

Frank Brady

www.IntegrityintheCourts.wordpress.com

Email: integrityinthecourts@gmail.com

Expose Corrupt Courts

Email:corruptcourt@gmail.com

Web: www.exposecorruptcourts.blogspot.com

PCAC membership inquiries should be directed to:

John T. Whitely

Chairman Executive Search Committee

Public Committee on Attorney Conduct

515 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 10022

Telephone 347-632-9775 E-mail: pcacinformation@gmail.com

Web: pcac.8k.com

About Litigation Recovery Trust

Founded in 1995, Litigation Recovery Trust is a New York based claims and rights administration organization. LRT pursues claims and causes of action worldwide, and processes single and group litigation claims, as well as general rights fees and awards. LRT also participates in legislative and administrative initiatives designed to protect or advance individual claims and rights.

About Integrity in the Courts Blog

Integrity in the Courts is a daily blog, which focuses on ethical and legal issues related to the administration of justice nationwide. Issues impacting both the judiciary and the bar are investigated, including compliance with a codes of judicial conduct, the codes of professional responsibility. Violations of law and failure to abide by codes of conduct are monitored, together with actions leading to disciplinary rulings, including admonishment, reprimand, censure, suspension or loss of licenses to practice law.

About Expose Corrupt Courts

Since beginning publication in March 2007, Expose Corrupt Courts has become one of the leading sources of both public and inside information concerning bench and bar misconduct. While the blog focuses primary attention on the court system of New York State, it regularly covers stories of interest throughout the U.S. Expose Corrupt Courts has led coverage of the massive corruption charges that have been filed against the attorney grievance committees in New York that have resulted in the filing of over a dozen law suits with the federal district court in Manhattan.

Executive Director

Litigation Recovery Trust

515 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 10022

Telephone 6462019269

E-mail: lrtinformation@gmail.com

Web: litigationrecoverytrust.8k.com

Frank Brady

www.IntegrityintheCourts.wordpress.com

Email: integrityinthecourts@gmail.com

Expose Corrupt Courts

Email:corruptcourt@gmail.com

Web: www.exposecorruptcourts.blogspot.com

PCAC membership inquiries should be directed to:

John T. Whitely

Chairman Executive Search Committee

Public Committee on Attorney Conduct

515 Madison Avenue

New York, New York 10022

Telephone 347-632-9775 E-mail: pcacinformation@gmail.com

Web: pcac.8k.com

About Litigation Recovery Trust

Founded in 1995, Litigation Recovery Trust is a New York based claims and rights administration organization. LRT pursues claims and causes of action worldwide, and processes single and group litigation claims, as well as general rights fees and awards. LRT also participates in legislative and administrative initiatives designed to protect or advance individual claims and rights.

About Integrity in the Courts Blog

Integrity in the Courts is a daily blog, which focuses on ethical and legal issues related to the administration of justice nationwide. Issues impacting both the judiciary and the bar are investigated, including compliance with a codes of judicial conduct, the codes of professional responsibility. Violations of law and failure to abide by codes of conduct are monitored, together with actions leading to disciplinary rulings, including admonishment, reprimand, censure, suspension or loss of licenses to practice law.

About Expose Corrupt Courts

Since beginning publication in March 2007, Expose Corrupt Courts has become one of the leading sources of both public and inside information concerning bench and bar misconduct. While the blog focuses primary attention on the court system of New York State, it regularly covers stories of interest throughout the U.S. Expose Corrupt Courts has led coverage of the massive corruption charges that have been filed against the attorney grievance committees in New York that have resulted in the filing of over a dozen law suits with the federal district court in Manhattan.

The Wall Street Journal: Checks and Judicial Balances

Checks and Judicial Balances

The Wall Street Journal - June 14, 2008 - Page A10

Here's a weekend daydream: What if on Monday, you walked into work and gave yourself a raise? That's what happened in New York this week, when a state judge ordered the Governor and state legislature to pony up bigger paychecks for him and the rest of his judicial friends. It's the perfect plan – if only it weren't for that inconvenient detail about separation of powers. The ruling, by New York Supreme Court Justice Edward Lehner, commands the state Senate and Assembly to pass a pay raise for judges in the next 90 days – and make some provision to retroactively compensate them for the lean years. The four plaintiffs in the suit suggested $600,000 each would do the trick. Multiplied out for the entire New York Judiciary, that would put New York taxpayers on the line for $700 million.

New York Governor David Paterson was unamused. Only the state legislature has the power to set judicial salaries, his office rightly pointed out in a statement. The judge's decision "flies in the face of the state constitution." There's more where that came from. Still pending before Judge Lehner is a separate suit brought by New York State Chief Judge Judith Kaye, who has retained New York attorney Bernard Nussbaum to sue the Governor and legislature for a raise for all 3,000 New York judges. Judge Lehner will thus be expected to rule in a case in which he is effectively a plaintiff, and in which he is also judging a complaint by his judicial superior.

The suits are necessary, say the judges, because legislators will raise their salaries only when they also raise their own, a fact which has left paychecks unaltered for a decade. That, in Judge Lehner's words, represents an "unconstitutional interference upon the independence of the judiciary." After a decade of inflation, judges say their salaries have been effectively cut – something which is prohibited by law. At those rates, they say they now make less than what's pocketed by first-year associates at big law firms. But few would consider their salaries fodder for Oliver Twist. Chief Judge Kaye makes the most, at $156,000 a year, while others earn about $136,700. By comparison, Members of the U.S. Congress now make $169,300 a year. A memorandum of law filed on behalf of Governor Paterson and state Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver in Judge Kaye's case notes that judges are already extremely well paid relative to the state workforce.

We have some sympathy for the judges, most of whom could make far more in private life. But then they also have extended tenure. To attract better people to the bench, we'd be willing to swap higher pay for term limits. New York judges may have a legitimate complaint about salary erosion, but they are exceeding their own legal authority by asserting the right to overrule the elected branches and set their own pay – about as basic a legislative function as one can imagine. Most judges choose their robes not for the salary but for the honor and significant authority, and, dare we say, the chance to serve the public. The hours are good, the work is interesting and they don't suffer the indignities of work life that are routine for the first-year associates whose salaries trump theirs. That, as they say, is priceless.

The Wall Street Journal - June 14, 2008 - Page A10

Here's a weekend daydream: What if on Monday, you walked into work and gave yourself a raise? That's what happened in New York this week, when a state judge ordered the Governor and state legislature to pony up bigger paychecks for him and the rest of his judicial friends. It's the perfect plan – if only it weren't for that inconvenient detail about separation of powers. The ruling, by New York Supreme Court Justice Edward Lehner, commands the state Senate and Assembly to pass a pay raise for judges in the next 90 days – and make some provision to retroactively compensate them for the lean years. The four plaintiffs in the suit suggested $600,000 each would do the trick. Multiplied out for the entire New York Judiciary, that would put New York taxpayers on the line for $700 million.

New York Governor David Paterson was unamused. Only the state legislature has the power to set judicial salaries, his office rightly pointed out in a statement. The judge's decision "flies in the face of the state constitution." There's more where that came from. Still pending before Judge Lehner is a separate suit brought by New York State Chief Judge Judith Kaye, who has retained New York attorney Bernard Nussbaum to sue the Governor and legislature for a raise for all 3,000 New York judges. Judge Lehner will thus be expected to rule in a case in which he is effectively a plaintiff, and in which he is also judging a complaint by his judicial superior.

The suits are necessary, say the judges, because legislators will raise their salaries only when they also raise their own, a fact which has left paychecks unaltered for a decade. That, in Judge Lehner's words, represents an "unconstitutional interference upon the independence of the judiciary." After a decade of inflation, judges say their salaries have been effectively cut – something which is prohibited by law. At those rates, they say they now make less than what's pocketed by first-year associates at big law firms. But few would consider their salaries fodder for Oliver Twist. Chief Judge Kaye makes the most, at $156,000 a year, while others earn about $136,700. By comparison, Members of the U.S. Congress now make $169,300 a year. A memorandum of law filed on behalf of Governor Paterson and state Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver in Judge Kaye's case notes that judges are already extremely well paid relative to the state workforce.

We have some sympathy for the judges, most of whom could make far more in private life. But then they also have extended tenure. To attract better people to the bench, we'd be willing to swap higher pay for term limits. New York judges may have a legitimate complaint about salary erosion, but they are exceeding their own legal authority by asserting the right to overrule the elected branches and set their own pay – about as basic a legislative function as one can imagine. Most judges choose their robes not for the salary but for the honor and significant authority, and, dare we say, the chance to serve the public. The hours are good, the work is interesting and they don't suffer the indignities of work life that are routine for the first-year associates whose salaries trump theirs. That, as they say, is priceless.

Tuesday, June 24, 2008

AP: Lawyers Were Greedy, Alcoholic or Simple-Minded...

Lawyers Were Greedy, Alcoholic or Simple-Minded, Depending on Who's Talking

The Associated Press (New York Lawyer) by Brett Barrouquere - June 24, 2008

Three lawyers accused of defrauding their clients in a $200 million diet drug settlement were greedy, a prosecutor charged Monday during closing arguments of the high-profile trial. But a defense attorney said the attorneys did not commit any crime. U.S. Attorney Laura Voorhees told jurors in Covington, Ky., on Monday morning that the three lawyers were motivated by greed. She said the lawyers should have been paid $60 million to settle a lawsuit over the diet drug fen-phen, but walked away with $127 million. "But $60 million wasn't enough. Think of it, ladies and gentlemen, the audacity of these attorneys," Voorhees said. Attorneys Shirley Cunningham Jr., William Gallion and Melbourne Mills Jr. are being tried on charges of wire fraud conspiracy. If convicted, they could receive up to 20 years in prison. Defense attorneys told jurors Monday afternoon that their clients did not commit any crimes. Jim Shuffett, who represents Mills, said his client was "a severe alcoholic" and that made him unable to think rationally.

"If these other two gentlemen had been intending to steal $65 million, they would have not have included a bad alcoholic," Shuffett said. "That's insane." Shuffett described Gallion, Cunningham and Mills as personal injury lawyers who may not have been able to grasp the complexities of the class action settlement. "I don't think they've figured out how to read that settlement agreement yet," Shuffett said. "It's too complicated." Stephen Dobson, who represents Cunningham, sought to minimize his client's role in the settlement and anything that may have gone wrong. "Mr. Cunningham gave no instructions, no directions," Dobson said. Dobson said Cunningham lacked criminal intent, a key ingredient in proving fraud charges. O. Hale Almand, who represents Gallion, said his client documented every step to ensure the settlement was handled properly. Almand also attacked one of the witnesses, Stanley Chesley.

The three defendants hired Chesley, a class action specialist from Cincinnati, to reach a settlement with American Home Products, the maker of the diet drug. Chesley, who received immunity from prosecution, testified earlier at trial that he did nothing wrong. He also had said he had found the handling of parts of the settlement unusual. Jurors are expected to return Tuesday morning to receive final instructions and begin deliberations in the six-week-long trial. The case has been closely followed in Kentucky and the horse racing industry because Gallion and Cunningham are part-owners of 2007's Horse of the Year, Curlin.

The Associated Press (New York Lawyer) by Brett Barrouquere - June 24, 2008

Three lawyers accused of defrauding their clients in a $200 million diet drug settlement were greedy, a prosecutor charged Monday during closing arguments of the high-profile trial. But a defense attorney said the attorneys did not commit any crime. U.S. Attorney Laura Voorhees told jurors in Covington, Ky., on Monday morning that the three lawyers were motivated by greed. She said the lawyers should have been paid $60 million to settle a lawsuit over the diet drug fen-phen, but walked away with $127 million. "But $60 million wasn't enough. Think of it, ladies and gentlemen, the audacity of these attorneys," Voorhees said. Attorneys Shirley Cunningham Jr., William Gallion and Melbourne Mills Jr. are being tried on charges of wire fraud conspiracy. If convicted, they could receive up to 20 years in prison. Defense attorneys told jurors Monday afternoon that their clients did not commit any crimes. Jim Shuffett, who represents Mills, said his client was "a severe alcoholic" and that made him unable to think rationally.

"If these other two gentlemen had been intending to steal $65 million, they would have not have included a bad alcoholic," Shuffett said. "That's insane." Shuffett described Gallion, Cunningham and Mills as personal injury lawyers who may not have been able to grasp the complexities of the class action settlement. "I don't think they've figured out how to read that settlement agreement yet," Shuffett said. "It's too complicated." Stephen Dobson, who represents Cunningham, sought to minimize his client's role in the settlement and anything that may have gone wrong. "Mr. Cunningham gave no instructions, no directions," Dobson said. Dobson said Cunningham lacked criminal intent, a key ingredient in proving fraud charges. O. Hale Almand, who represents Gallion, said his client documented every step to ensure the settlement was handled properly. Almand also attacked one of the witnesses, Stanley Chesley.

The three defendants hired Chesley, a class action specialist from Cincinnati, to reach a settlement with American Home Products, the maker of the diet drug. Chesley, who received immunity from prosecution, testified earlier at trial that he did nothing wrong. He also had said he had found the handling of parts of the settlement unusual. Jurors are expected to return Tuesday morning to receive final instructions and begin deliberations in the six-week-long trial. The case has been closely followed in Kentucky and the horse racing industry because Gallion and Cunningham are part-owners of 2007's Horse of the Year, Curlin.

Monday, June 23, 2008

Manhattan Prosecutor's Shocker

PROSECUTOR'S SHOCKER: I THREW MURDER CASE

The New York Post by LAURA ITALIANO - June 23, 2008