The New York Times by Clyde Haberman - January 31, 2011

Guy J. Velella, a former state senator from the Bronx who died last week, was bidden farewell at a funeral service on Monday. His legacy, however, lives on. Among other things, Mr. Velella will be remembered for having turned a career of public service into one of public shame by taking bribes and going to jail for his corruption. He will also be remembered as someone who pocketed public money even after pleading guilty in 2004. Every year, his conscience unburdened, Mr. Velella collected a state pension of more than $75,000. “The law says I’ve earned it,” he told The Daily News a few months ago. “I’m entitled to it. I take it.” Mr. Velella was not the only corrupt public official with a sense of entitlement. That is why new calls have arisen to change the law so that bribe takers, kickback schemers, pay-to-play chiselers and other finaglers holding public office do not enjoy the same retirement privileges as their honest colleagues. In Albany, the lineup of cosseted crooks has grown long. High on the list is Alan G. Hevesi, the disgraced former state comptroller, who receives an annual state pension of about $105,000. Others picking up impressive pensions after being found guilty of crimes have included Joseph L. Bruno, the former State Senate majority leader (about $96,000 a year); former Assemblyman Clarence Norman Jr. ($43,000); former Assemblywoman Gloria Davis ($62,000); and Anthony S. Seminerio, a former assemblyman who died in prison four weeks ago ($71,000). A new addition is Vincent L. Leibell III, a former state senator from Putnam County, who pleaded guilty in December to charges rooted in a kickback scheme. Like Mr. Seminerio, he is eligible for a yearly state pension of $71,000. In some Albany circles, there is a feeling that enough is enough. It is shared by the present state comptroller, Thomas P. DiNapoli, who got his job in 2007 after Mr. Hevesi washed out. The other day, Mr. DiNapoli proposed legislation to take away pensions from an array of elected officials and their appointees — potentially thousands of people at state and local levels — if they are convicted of felony charges involving an abuse of office. Because of limitations imposed by the State Constitution, this penalty would apply only to future officials. Mr. Hevesi and the others could keep cashing those pension checks. But to encourage present officeholders to walk the straight and narrow, Mr. DiNapoli recommended that wrongdoers be fined as much as double whatever money they made from their unlawful behavior.

“Public confidence in government has been bruised and battered,” the comptroller said, a statement that would seem to defy contradiction. The goal, he said, is to “remind every public official that violating the public trust will not to be tolerated.” Some other states have comparable pension-stripping laws, and Mr. DiNapoli’s aides said he was confident that New York would enact its own this year. Others are not so sure. They include State Senator Liz Krueger of Manhattan, who has sponsored bills along those lines since the Velella scandal burst open seven years ago. She has gotten nowhere. One argument she often hears, Ms. Krueger said Monday, is that to take away pensions would unfairly penalize family members who may depend on that money, and who did nothing wrong themselves. At least, she said, “that’s the argument that people can make to me with a straight face.” Her response is: “You know, when real people go to jail, their families pay a price, too. I thought we were sort of real people.” Ms. Krueger said she doubted that “a free-standing bill” would get enough votes for passage. Instead, she suggested that pension forfeiture be “rolled into an ethics reform package” that is expected from Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo. Whatever form the legislation may take, the principle remains the same. It’s quite simple: If you violate the public’s trust, you don’t deserve the public’s money. “I really believe that you, the public, get to hold me to a higher standard,” Ms. Krueger said. No one, after all, forced her to run for office. But don’t be too glum, you in high places with sticky fingers. Things could always be worse. Forfeit your pension? How about forfeiting your life? In China, they execute your kind. haberman@nytimes.com

********** Related Story..... When Our Public Officials Lie......

When Police Officers Lie

Legal System Struggles With How to React When Police Officers Lie

The Wall Street Journal by AMIR EFRATI - January 29, 2009

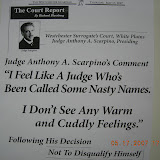

It's one of the most common accusations by defendants and defense attorneys -- that police officers don't tell the truth on the witness stand. Of course, defendants themselves can be the ones lying, but the problem of police perjury -- and what can be done about it -- is being debated anew. Fueling the discussion are recent court cases in New York City and Boston that indicated officers may have lied and a U.S. Supreme Court ruling this month that could have broader implications for cases in which improperly obtained evidence is in dispute.

Questionable testimony by police comes up most often in firearm- or drug-possession cases in which officers often testify that a defendant had a bulge in his pocket -- which they thought might be a gun -- or dropped drugs in plain sight as they approached him, giving the officers the right to seize the contraband. Defense lawyers say in many of these cases, officers are "testilying" and that the guns or drugs were actually discovered when their clients were unjustly frisked by officers. They also say testilying frequently occurs in more serious cases. In Boston, a federal judge last week ruled that a police officer there falsely testified at a pretrial hearing in a gun-possession case about the circumstances of the defendant's arrest. The judge, Mark Wolf, is considering sanctions against the prosecutor for not immediately disclosing that the officer's testimony contradicted what he told prosecutors beforehand.

A federal judge in Brooklyn, N.Y., last fall ruled that a U.S. marshal and a New York City police officer lied when they testified that a defendant dropped two bags of drugs in front of them and then invited the officers to his apartment, where he revealed a large cache of cocaine. Though few officers will confess to lying -- after all, it's a crime -- work by researchers and a 1990s commission appointed to examine police corruption shows there's a tacit agreement among many officers that lying about how evidence is seized keeps criminals off the street. To stem the problem, some criminal-justice researchers and academic experts have called for doing polygraphs on officers who take the stand or requiring officers to tape their searches.

A Supreme Court ruling this month, however, suggests that a simpler, though controversial, solution may be to weaken a longstanding part of U.S. law, known as the exclusionary rule. The 5-4 ruling in Herring v. U.S. that evidence obtained from certain unlawful arrests may nevertheless be used against a criminal defendant could indicate the U.S. is inching closer to a system in which officers might not be tempted to lie to prevent evidence from being thrown out. Criminal-justice researchers say it's difficult to quantify how often perjury is being committed. According to a 1992 survey, prosecutors, defense attorneys and judges in Chicago said they thought that, on average, perjury by police occurs 20% of the time in which defendants claim evidence was illegally seized. "It is an open secret long shared by prosecutors, defense lawyers and judges that perjury is widespread among law enforcement officers," though it's difficult to detect in specific cases, said Alex Kozinski, a federal appeals-court judge, in the 1990s. That's because the exclusionary rule "sets up a great incentive for...police to lie."

Police officers don't necessarily agree, says Eugene O'Donnell, a former police officer and prosecutor who teaches law and police studies in New York. "Perjury is endemic in the court system, but officers lie less than defendants do because generally they aren't heavily invested in the outcome of the cases," he says. Testilying may have taken off after a 1961 Supreme Court decision boosted the exclusionary rule by requiring state courts to exclude -- or throw out -- some evidence seized in illegal searches, such as when police frisk people without probable cause or search a residence without a warrant. Immediately after the decision, Mapp v. Ohio, studies showed that the number of annual drug arrests in the U.S. -- most cases are prosecuted in state court -- didn't change much but there was a sharp increase in officers claiming that suspects dropped drugs on the ground. "Either drug users were suddenly dropping bags all over the place or the cops were still frisking but saying the guy dropped the drugs," says John Kleinig, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

This month's Supreme Court decision added an exception to the exclusionary rule by holding that the prosecution of an Alabama man for drug- and firearm-possession charges was valid, even though the contraband was found after the man was wrongly arrested and searched. Police officers had mistakenly thought he was subject to an arrest warrant. Throwing out evidence because of wrongful searches and arrests "is not an individual right and applies only where its deterrent effect outweighs the substantial cost of letting guilty and possibly dangerous defendants go free," wrote Chief Justice John Roberts. Civil liberties advocates and defense lawyers say losing the exclusionary rule would harm the public. "We'd risk far greater invasions of privacy because officers would have carte blanche to do outrageous activity and act on hunches all the time," says JaneAnne Murray, a criminal defense lawyer in New York. Write to Amir Efrati at amir.efrati@wsj.com